Introduction

Many modern wireless communication systems use high-order QAM with a large peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR) and therefore require linear RF amplifiers. This often leads to low efficiency in the final RF power amplifiers.

The Doherty amplifier provides a way to maintain linearity while significantly improving efficiency.

How a Doherty Power Amplifier Works

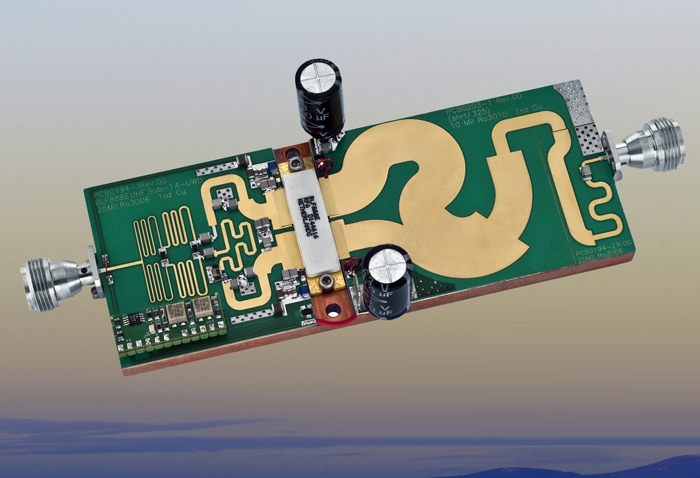

A Doherty power amplifier is an RF design based on class B biased amplifier sections that achieves high efficiency by combining two amplifier paths. One amplifier section handles lower amplitude signal conditions. A second amplifier is introduced to provide additional capability for higher-level signals without driving the amplifier into heavy compression.

In this way, a Doherty amplifier can offer both linearity and improved efficiency.

History

The Doherty amplifier configuration was invented by William H. Doherty at Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1936.

Although the original concept was developed in the vacuum-tube era, the Doherty architecture addressed the need to operate high-power transmitters while maintaining reasonable power efficiency to reduce cost, heat dissipation, and operating expense. Vacuum tubes were power hungry, so any efficiency gain reduced power consumption and system footprint.

The first RF circuit implementations of the Doherty amplifier used two vacuum-tube amplifiers, both biased in class B, capable of delivering tens of kilowatts to an antenna.

Applications and Requirements

Doherty amplifiers are widely used in cellular base station transmitters and in many other radio communication systems that require higher power and good efficiency. With millions of base stations worldwide, efficiency improvements generate significant operating cost savings.

Doherty power amplifiers increase efficiency while allowing linear operation. Mobile communications and other wireless systems need to lower power consumption and improve overall efficiency, so reducing power usage is a key requirement.

As mobile systems such as UMTS, HSPA, 4G LTE, and 5G use modulation formats with increasing PAPR, linearity becomes critical to minimize data errors.

Conventional linear amplifiers are not very efficient, so techniques like the Doherty principle are used to keep RF power amplifiers efficient.

Amplifier Operation and PAPR

Efficiency is defined as output power divided by input power, but it is affected by many factors including PAPR.

To understand how PAPR affects efficiency, consider amplifier operation. In linear mode an output device must be continuously biased on, and the output voltage swings between two limits.

When operated in this mode, the theoretical maximum efficiency is about 50% for class A, and practical levels are lower because of circuit losses and the fact that signals often do not reach the amplifier's maximum level.

To achieve higher efficiency, an amplifier can be driven into compression. This works well for constant-envelope signals such as FM, which do not have amplitude content. The only distortion is additional harmonics, which can be filtered with RF filters.

However, when amplitude-modulated signals are passed through a compressed amplifier, amplitude distortion occurs. For current data transmission systems such as UMTS, HSPA, 4G LTE, and 5G, waveforms include amplitude components in addition to phase components and thus require linear RF amplifiers.

Higher PAPR makes the situation worse because the amplifier must accommodate peaks while maintaining linearity, so average power must be kept low, reducing efficiency.

Doherty power amplifiers adapt to signals with high PAPR while maintaining good efficiency. They do this by using two amplifier circuits within one RF amplifier to handle different operating conditions. The biasing and roles of the two amplifiers differ.

Carrier and Peaking Amplifiers

Carrier amplifier: This part of the Doherty amplifier typically operates in class A or AB and provides gain at all power levels. It is optimized for the average amplitude level of the signal.

Peaking amplifier: When the carrier amplifier approaches its limit, the second RF amplifier begins to contribute. The peaking amplifier provides the extra power capability that the carrier amplifier cannot provide on its own.

A key aspect of Doherty operation is that the peaking amplifier only runs when needed. If it ran continuously, the efficiency gains would be lost. The goal is to keep the carrier amplifier active while the peaking amplifier engages before the carrier amplifier enters significant compression.

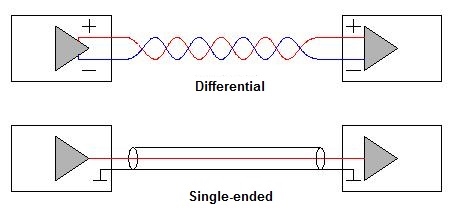

RF Splitters, Combiners, and Phase Matching

Beyond the amplifiers themselves, a Doherty RF design requires splitters and combiners. These components route power to the two amplifiers and then combine their outputs to form the composite output. Splitters and combiners must accommodate the phase and matching requirements of both paths.

Doherty Variants

There are several Doherty amplifier variants:

- Symmetric Doherty amplifier: The straightforward approach using two identical RF amplifiers. It is simpler but cannot deliver the improved performance of asymmetric designs.

- Asymmetric Doherty amplifier: The most widely used format. It uses two different RF amplifiers, with the peaking amplifier having higher power capability. This allows the lower-power amplifier to efficiently serve lower signal levels while the peaking amplifier handles peaks, yielding better overall performance.

- Digital Doherty amplifier: Traditionally, analog techniques have been applied to Doherty designs, but different bias schemes and phase shifts limit bandwidth and efficiency. Digital techniques are being developed for Doherty amplifiers. With digital Doherty, lookup tables can measure and correct dynamic phase alignment between the carrier and peaking amplifiers. Digital predistortion is then applied, and DPD is used in the peaking amplifier signal path. Using DPD makes the amplitude/phase response of the peaking amplifier relatively constant, so adding a fixed phase offset at the input of the lagging path can correct phase differences between the two paths more easily.

Digital Doherty approaches are not yet widespread, but they address many limitations of fully analog methods and can offer significant improvements.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Key advantages

- Higher efficiency levels.

- Less complex than envelope tracking while still improving RF amplifier efficiency.

Key disadvantages

- Maintaining the required phase shift across a wide bandwidth is difficult, so Doherty amplifiers are limited to finite bandwidths.

- Higher cost than a single amplifier.

- Design is challenging to achieve optimal performance.

Despite drawbacks, Doherty amplifiers are increasingly used in cellular base stations and other radio systems where higher efficiency is required. Cellular networks can consume significant power, so operators seek to reduce power consumption. At the same time, amplifiers must remain linear to avoid distortion and spectral regrowth that can occur when amplifiers become nonlinear.