Introduction

It is often said that automotive software differs from Internet software and should be treated differently. Common assertions include:

- Automotive software has stricter real-time requirements.

- Automotive software has higher safety requirements.

- Automotive software is more tightly coupled with hardware.

- The programming languages used in automotive software differ.

- Automotive software uses different operating systems.

- Development environments and toolchains for automotive software differ.

These points are not wrong, but they are not entirely definitive. First, with cockpit, automated driving, and backend software becoming prominent and the electronic/electrical architecture evolving, the scope of automotive software has expanded considerably. Second, these are technical characteristics; technical differences only distinguish the "software of a car" from the "software of the Internet" rather than defining a categorical divide between "automotive software" and "Internet software."

To adopt a holistic perspective, this article focuses on integration, which is central to the distinctiveness of automotive software. Specifically, integration can be divided into five levels:

- Integrating software units together

- Integrating software onto hardware

- Integrating hardware into mechanical housings

- Integrating ECUs into subsystems

- Integrating subsystems into the vehicle

Level 1: Integrating software units together

At its narrowest, software integration means combining verified software units into a complete software artifact. Operationally, this involves integrating different .c or .h files and configuration files using integration tools to build a software package.

Because projects are complex, integration is one stage in the overall software project management chain.

First, development engineers receive defects, changes, or tasks via the ALM workflow tool, make local code changes, and then push the code to the repository.

Second, integration engineers should receive integration tasks through the workflow tool; tasks should specify branch strategy, delivery objectives, schedule, and unit information. Based on these inputs, the integration engineer performs the software build.

Third, integration engineers must verify their work by performing static or dynamic integration tests. Results typically include compiler warnings, code scan results, resource consumption data, stack analysis, code review outcomes, and smoke test results.

Fourth, integration engineers package executables, test reports, configuration data, issue lists, release notes, and other necessary materials for release.

Level 2: Integrating software onto hardware

Once a complete software package is ready, it must be integrated onto hardware, specifically flashed into MCUs and other chips.

In theory, integration is achieved via interfaces. Software-hardware integration relies on physical chip pins and logical software interfaces for data transmission. Common methods include:

- Programming directly through chip pins for production lines or prototypes.

- If hardware is already installed in the vehicle, flashing via OBD or USB.

- Remote update via OTA for out-of-field cases.

Ideally, these interfaces should be defined as part of the system architecture during development.

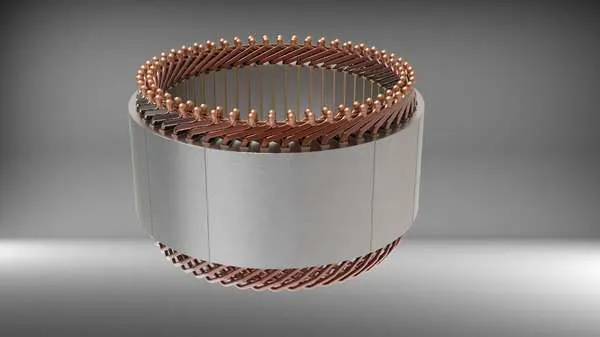

Level 3: Integrating hardware into mechanical housings

At this stage, the result is a circuit board with software. The next step is integrating the circuit board with mechanical housings, connectors, screens, and similar elements. This assembly, often realized as a batch of prototypes, yields an ECU or control module.

Because automotive electronics must endure complex and harsh operating conditions, this integration significantly affects software performance. For example, internal sensors may have modal and dimensional requirements related to their installation environment.

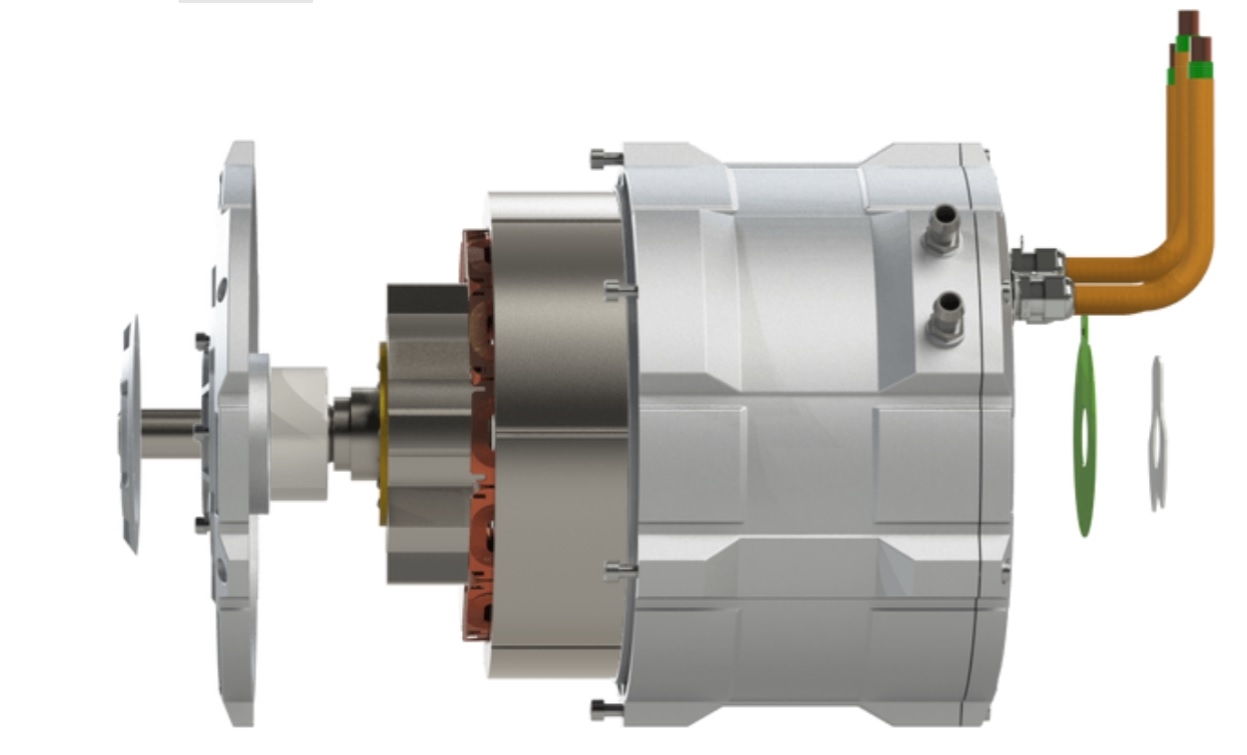

Level 4: Integrating ECUs into subsystems

An ECU together with a set of sensors and actuators forms a subsystem that delivers a specific function, such as propulsion, braking, steering, passive safety, lighting, or advanced driver assistance.

At this level, integration typically involves connecting the ECU, sensors, and actuators with a wiring harness and mounting the ECU on the vehicle. Sensors and actuators often come from different organizations, making this integration step particularly important.

The integration outcome must be validated in the vehicle environment through layout confirmation, modal analysis, sensor signal calibration, electronic counterpart debugging, subsystem function verification, production line validation, and environmental and reliability tests such as EMC, vibration, shock, water spray, salt fog, and temperature extremes.

From a software perspective, joint debugging with counterpart components is critical. Increasingly, electronic functions require multi-module coordination; diagnostic and communication issues are frequently discovered at this stage.

Many subsystem performance characteristics also require software calibration and matching within the full vehicle environment.

Level 5: Integrating subsystems into the vehicle

Traditionally, vehicle subsystems or domains were largely isolated, so their assembly was primarily mechanical. However, the electronic/electrical architecture is moving toward cross-subsystem and cross-domain integration, domain fusion, and centralization. As subsystem boundaries become more blurred, many functional attributes must be validated at the vehicle level or at the terminal.

Final remarks

Overall, when developing automotive software, it is important to recognize that all code ultimately serves the vehicle's behavior.

The multi-layered integration seen in the automotive industry has historical roots in the global modular division of labor and procurement of automotive parts. While this division and standardization offer clear benefits, they also increase the number of integration points. More integration points complicate communication and make solution integration more difficult, which must be carefully considered in automotive software development.

In the long term, the architectural trend toward centralization is reducing integration points, which will reduce the value and necessity of certain types of integration.