Introduction

Laser technology and lasers, which emerged in the 1960s, are among the most significant scientific and technological advances of the twentieth century. Rapid development in laser technology has intersected with many disciplines to form new interdisciplinary fields such as optoelectronics, information optics, laser spectroscopy, nonlinear optics, ultrafast lasers, quantum optics, fiber optics, guided-wave optics, laser medicine, laser biology, and laser chemistry. These interdisciplinary advances have expanded laser applications into most sectors of the economy.

Laser Sensor Principle

A laser sensor performs measurements using laser technology. It typically consists of a laser source, a laser detector, and measurement electronics. Laser sensors enable non-contact, long-distance measurement with high speed, high accuracy, wide range, and strong resistance to optical and electrical interference.

Lasers differ from ordinary light and require a laser medium to generate coherent radiation. In the laser medium, atoms normally occupy a lower energy level E1. When illuminated by light of appropriate frequency, atoms in E1 absorb photon energy and transition to a higher energy level E2. The photon energy is E = E2 - E1 = h·v, where h is Planck’s constant and v is the photon frequency. Conversely, under illumination at frequency v, atoms in E2 can be induced to transition to E1 and emit photons, a process called stimulated emission. By achieving population inversion, stimulated emission dominates and, together with resonant optical feedback from mirrors, produces an amplified coherent beam called laser light.

Lasers have three key characteristics:

- High directionality: laser beams have very small divergence, so a beam may only spread a few centimeters at distances of several kilometers.

- High monochromaticity: laser frequency linewidth is typically orders of magnitude narrower than ordinary light.

- High brightness: focused laser beams can produce extremely high irradiances.

Overview: Two Main Laser Sensor Principles

The directionality, monochromaticity, and brightness of lasers enable non-contact long-distance measurement. Laser sensors are commonly used to measure length, distance, vibration, speed, and orientation, and they are also used for nondestructive testing and monitoring atmospheric pollutants. The following sections describe two primary laser sensor principles and their applications.

1. Laser Displacement Sensor

A laser displacement sensor takes advantage of laser directionality, monochromaticity, and brightness to perform non-contact long-range displacement measurements. As a modern measurement instrument, it substantially improves accuracy and reliability for displacement measurement and provides an effective non-contact method.

2. Laser Range Sensor

The operating principle of a laser range sensor is similar to radar. The sensor directs laser pulses to a target, measures the round-trip time, and multiplies by the speed of light to obtain the distance. Laser beam properties such as directionality, monochromaticity, and high power are critical for long-range measurement, target localization, improving the receiver signal-to-noise ratio, and ensuring measurement accuracy. For these reasons, laser rangefinders are widely used.

Laser ranging is an active optical detection method. The detection mechanism is: the system emits a beam (typically infrared or visible), the beam is scattered by the target surface and produces an echo signal, and the receiver and signal-processing hardware extract the desired measurement information from the returned echo.

The operating sequence is as follows: an operator issues a range command and the laser emits a pulse. Part of the pulse passes through a beam splitter to the pulse acquisition system as a reference pulse and starts the digital range timer. The remainder is sent to the target via a refracting prism. The transmit aperture typically includes optics to reduce beam divergence, increasing irradiance on the target and reducing interference from background objects.

The portion of the beam reflected from the target is collected by the receive optics, passes through a narrow-band optical filter to exploit the laser's monochromaticity and improve signal-to-noise ratio, and reaches an APD detector. The APD converts the optical signal into an electrical signal, which is then amplified and shaped. The shaped echo signal closes the timing interval processing module and stops the timer. From the measured time interval t, the target distance L is calculated as shown in the system equation:

In equation (1), c is the speed of light. The optical filter and aperture reduce background and stray light, lowering detector output noise. The pulse ranging precision can be expressed as:

From this expression, the timing interval precision of the system processing directly determines the pulse laser ranging accuracy:

Unique Advantages of Laser Sensors

Laser sensors are applicable in scenarios where other technologies cannot perform reliably. For example, for short-range precision position detection, ordinary photoelectric sensors can be sufficient. However, when targets are at longer distances or when target color varies, photoelectric sensors struggle.

Advanced background suppression sensors and triangulation sensors can handle color changes fairly well, but performance becomes less predictable when target angle varies or when the target is highly reflective. Typical photoelectric triangulation sensors also have limited ranges, often under 0.5 m. Ultrasonic sensors are often used for longer-range detection and are immune to color variations, but they have inherent limitations that make them unsuitable for certain cases:

- When the target is not approximately perpendicular to the transducer, since ultrasonic detection usually requires the target to be within about ±10° of normal incidence.

- When a very small beam diameter is needed, because a typical ultrasonic beam can be several centimeters wide at a few meters.

- When a visible spot is required for position calibration.

- In windy environments.

- In vacuum environments.

- In environments with large temperature gradients, since speed of sound varies with temperature.

- When rapid response is required.

Laser sensors can address all of these scenarios.

Applications in Manufacturing

In manufacturing, laser sensors are used for laser length measurement, laser ranging, laser vibration measurement, and laser speed measurement. Their non-contact, long-range capability makes them suitable for measuring length, distance, vibration, speed, and orientation, as well as for nondestructive testing and environmental monitoring.

Laser length measurement

Precision length measurement is a key capability in precision machinery and optical fabrication. Modern length metrology often relies on optical interference; measurement accuracy depends on light source monochromaticity. Because lasers offer extremely pure monochromatic light, laser length measurement provides high range and high accuracy.

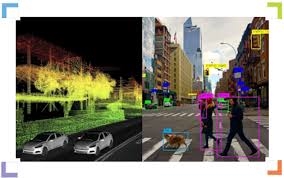

Laser ranging

Laser ranging operates like radio radar, measuring round-trip time and multiplying by light speed to obtain distance. The beam properties make laser ranging suitable for long distances, target localization, and high measurement accuracy. Based on laser rangefinders, lidar systems can also determine target bearing, velocity, and acceleration; they have been successfully used for satellite ranging and tracking.

Laser vibration measurement

Laser vibration measurement relies on the Doppler principle to measure object vibration velocity. Optics convert object motion into a Doppler frequency shift, which a photodetector converts to an electrical signal. After signal processing, the Doppler shift is translated into a velocity-proportional electrical signal and recorded. Advantages include ease of use, no need for a fixed reference, minimal influence on the object's vibration, broad frequency range, high accuracy, and large dynamic range. A drawback is susceptibility to stray light interference.

Laser speed measurement

Also based on the Doppler principle, laser velocimetry is widely used. A common instrument is the laser Doppler flowmeter, which measures airflow in wind tunnels, rocket propellant flow, jet exhaust velocity, atmospheric wind speed, and particle velocities in chemical reactions.

Conclusion

Compared with ordinary light sources, lasers offer many advantages that ordinary sources cannot replace, but lasers require dedicated laser sources and higher technical requirements. Development of laser sensing technology supports national capabilities in science, economy, and defense.