Introduction

Motion control and troubleshooting and maintenance of robots require a deep understanding of motors and all components and mechanisms within a robot.

Motion control involves using motors to position actuators and move them precisely. Although motion control is not always closed-loop, it differs from motor control, whose primary objective is to achieve and verify a known position or motion.

01 Stepper Motor Principles and Maintenance

Stepper motors are a type of brushless DC motor whose stator consists of multiple electromagnets arranged around a gear-like rotor. The ring-arranged magnets are divided into groups called phases. Energizing the phases in sequence causes the motor to "step" to the next position.

Microcontroller-based stepper drivers activate transistors in the appropriate sequence. A typical stepper motor resolution is 200 steps per revolution, while microstepping drivers can provide up to 1600 steps per revolution. Stepper drivers are sometimes called "choppers."

Stepper motors often run without feedback devices such as encoders or resolvers, which makes them a lower-cost positioning method compared with servos, but they also have limited holding torque. In addition to the motor and driver, an indexer is required. The indexer can be built into the driver and communicate with the main controller, or pulses can be sent from programmable controllers such as a PLC. Troubleshooting stepper systems may include checking voltages and communications in the control circuits and using an oscilloscope to view pulse signals.

02 Servo System Components and Maintenance

A servo or servomechanism uses feedback to control position and torque. Servos can be electric, hydraulic, or pneumatic, but most industrial automation servo systems are motor driven.

Servo motors may be brushed permanent-magnet DC, brushless permanent-magnet AC, or AC induction motors. They typically include an encoder or resolver and are often integrated with a gearhead. Motor assemblies usually have two cable connectors to separate encoder/sensor feedback signals from the motor power supply.

Servo drives accept pulse inputs from encoders and monitor torque via current sensing. Temperature sensors and brake control signals are sometimes included in the control cable. In general, servo drives are more complex than variable-frequency drives and often include built-in logic. Modern controllers almost always provide high-speed communication ports to coordinate motion with other controllers. This is typically an Ethernet-based protocol, although fiber optics may be used in some applications.

Servo control algorithms are based on PID control for position or torque. Motors must be tuned to match motor and load characteristics for optimal performance. For this reason, motors and drives from the same manufacturer are commonly supplied and used as matched pairs. Some motors integrate the drive and controller. These integrated servos can be networked to perform complex tasks or used as standalone positioners.

An important difference between servo motors and AC induction motors driven by VFDs is that servo motors provide holding torque at zero speed. If a motor shaft is displaced from its commanded position while powered, the motor will attempt to self-correct; failure to reach the preset position will generate a controller fault.

When coordinating motion, a "master" controller or position commonly adjusts the speed of other controllers. One axis' motion may depend on changes in another axis or a virtual axis. It is important to use a fast communication network dedicated to motion systems. Dedicated motion controllers can coordinate servo axes. Machine vision can be integrated to guide an end effector to the correct position. Motion controllers can be integrated into a PLC rack or used as standalone systems. Many include separate I/O modules and can be programmed with IEC 61131 PLC languages.

Troubleshooting servo systems generally requires electrical diagnostic methods plus knowledge of the platform software. Drives and controllers usually include built-in diagnostics to detect problems with the motor and connected load. Mechanical components such as couplings can also fail. Consult the documentation first.

03 Robot Motion Control and Path Awareness

Industrial robots are used for manufacturing and material handling tasks. Their physical configuration depends on the required function. Payload and speed requirements help determine the type of robot used in a specific application.

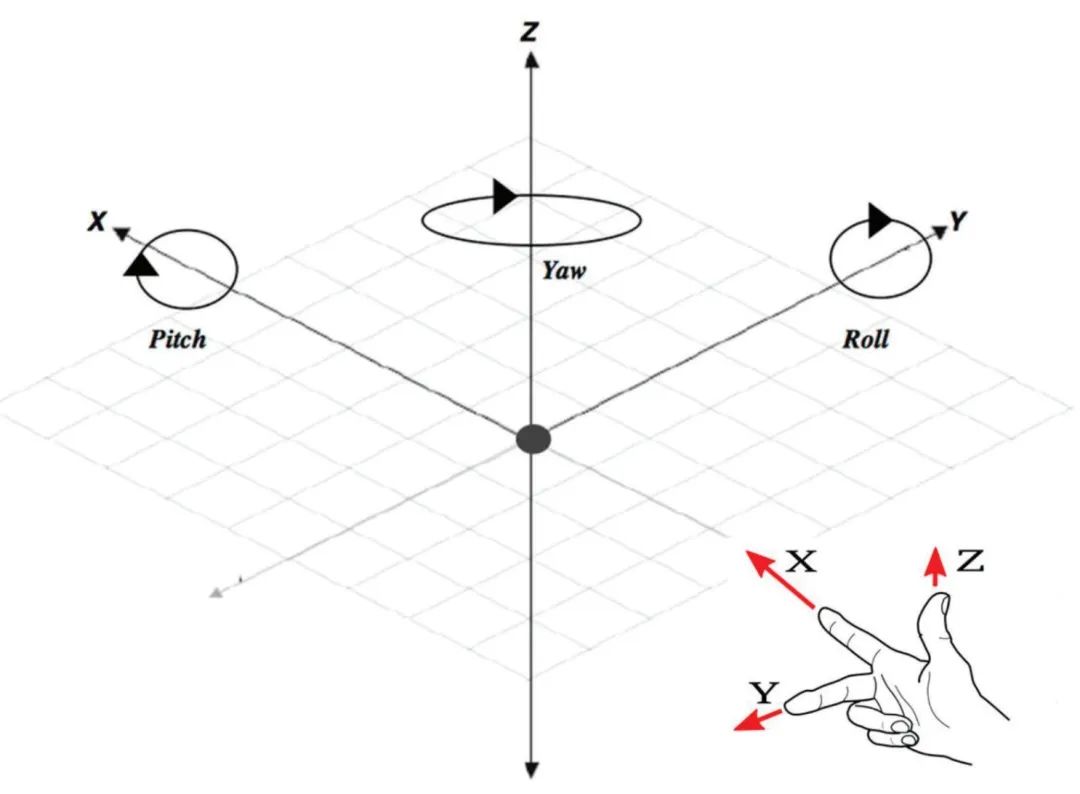

Robots may have up to 6 or 7 axes or as few as 3 axes. Two axes are required to reach an arbitrary point in the X-Y plane; three axes are required to reach any point in X-Y-Z space. To fully control the position and orientation of a tool at the end of an arm, three additional axes are needed: pitch, roll, and yaw.

Figure 3 illustrates the six axes required to reach any position and orientation in three-dimensional space, but robots use different coordinate systems and joint configurations can vary. The origin and orientation also differ by manufacturer and can usually be changed in software.

Robot coordinate axes and the right-hand rule.

X, Y, and Z positions are called Cartesian coordinates, but they can be defined from different reference points. If defined from the robot base or an environmental reference point, they are world coordinates. In this case, the origin frame is stationary. If addressed from the perspective of the end effector, they are tool coordinates, and the origin moves with the end effector. This can include offsets from the tool connection point to the tool contact point. Local coordinates can also be defined, typically with the origin set within the work area to allow replication of reference points for pallets or other local systems.

Individual joints can be controlled independently and are typically defined in degrees. Distances are commonly defined in metric units (mm) but can be scaled to user-defined units in software. In addition to X, Y, and Z, roll, pitch, and yaw are sometimes labeled with other letters such as U, V, and W.

The region a robot can reach is called the workspace. Planes and volumes can be defined within the cell to prevent collisions or ensure safety. Safety devices such as light curtains can also be integrated into the robot work cell.

Robot controllers continuously compute the position of the robot relative to reference points and the path. When moving along a defined path, axes must work in coordination, so a robot represents the ultimate form of coordinated motion control. This is why controllers are typically used to support tasks that implement and maintain position.

An important issue when working with robots is singularities. At a singularity, due to physical or mathematical constraints, the robot cannot move the end effector along a particular path. The robot may end up in a configuration where it cannot rotate the tool about a specific point, sometimes referred to as gimbal lock. In other configurations, moving a joint in certain directions may damage cables or hoses, so care is needed when moving near singularities or when a joint is rotated too far. There are often multiple joint configurations that achieve the same tool position and orientation, referred to as redundant degrees of freedom.

Robot controllers typically perform logic functions and operate external devices but are often integrated into the work cell and connected to a master controller such as a PLC. The controller may be connected to the robot unit by power and signal cables or mounted in the robot base. Connections can be 24 V dc physical connections, communication links, or pass-through ports and connectors routed to the end effector or tool. Pass-through ports commonly include pneumatic hoses. Robots are classified by physical configuration. Six-axis articulated arms are common in heavy-payload applications, while 4-axis SCARA robots are typically used for oriented pick-and-place. Delta configurations are very fast and are often used in electronics for component placement. Collaborative robots, or cobots, are designed for direct interaction with humans in shared spaces and differ from the configurations described here.

04 Making Robot Programming Easier

Robots can be programmed by computer or via a teach pendant. Two types of code must be programmed: programs and position data. To move from one position to another, a robot's end effector first needs defined start and end positions, and a program must be written to define how to get there. This may involve intermediate positions and external signals to indicate object presence or start motion.

Positions can be defined in software lists, but using a teach pendant is easier. A teach pendant allows an operator to move individual axes and "drive" the robot to the required position. For precision and safety, this is typically done at low speed. When manipulating the robot, a three-position dead-man switch must be pressed. A spring-loaded switch must be held in the middle position; if it is fully pressed or released, the robot will not move.

A program is a series of moves between positions. Programs can be triggered individually or linked together. Robot languages vary, and vendor-specific languages are common. They often resemble Basic or assembly languages with JUMP and MOVE statements. Other higher-level scripting languages can build data structures or implement mathematical algorithms, for example to compute paths or positions. Some languages support parallel processing, allowing a robot to perform multiple tasks concurrently, such as computing motion vectors while a camera tracks a moving object.

Position tables and programs reside in separate memory areas, so one can be changed without affecting the other. This allows positions to be edited by computer or teach pendant to modify tasks. Positions are usually defined in world coordinates, but the joint positions of a 6-axis robot may differ while producing the same end effector pose. Positions can be taught by driving the robot into a specific joint configuration and selecting "teach," or by using a "guiding" technique that relaxes the axes so the user can manually push them through a series of positions to describe a path.

05 Troubleshooting and Maintenance Considerations for Robots

Robot troubleshooting and maintenance include fine-tuning positions, replacing end-effector tools, and maintaining electrical or pneumatic connections. Like motion controllers and VFDs, robot controllers indicate system issues by providing fault data. Most faults cause the robot to stop moving and may require the operator to move the robot to a safe position after correcting the fault.

Robot work cells typically include an interface with a PLC and an HMI. The PLC communicates with the robot and displays received fault codes and other data on the HMI. This involves two communication links (robot-PLC and PLC-HMI), so ensuring both are functioning is important.

End effectors may use M8 or M12 cable connections, junction boxes with terminals, AS-i actuator-sensor interface, or Ethernet remote I/O. If a sensor terminal has a cover, it helps to know the type of communication interface in advance. Check documentation or examine the fixture or tool area to identify these connections.

A typical layout of a robot work cell shows lines in different colors to indicate that connections between components may be discrete wiring, communication links, pneumatics, or a combination of power and feedback wiring when the robot is connected to a controller. This complexity can make troubleshooting challenging because it spans mechanical, electrical, and control disciplines.

There are often actuators within a system that are not controlled by the robot controller, such as part clamping devices. These require handshake signals between the PLC and the robot controller. External systems for material handling and transfer may also interface with the PLC, and multiple robots can exist in a cell. Preventing collisions between multiple robots and tools can become very complex. Safety devices such as light curtains, floor scanners, and door switches may interface with the robot controller and the PLC. Machine vision can be used to locate parts for the robot, introducing another layer of system complexity.