Definition

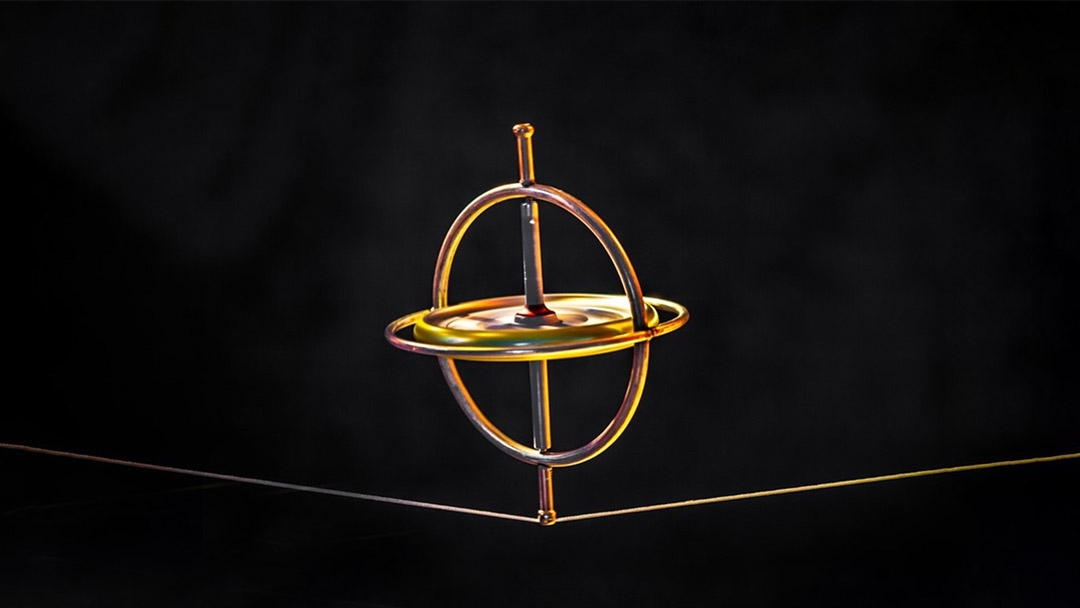

A gyroscope, also called an angular velocity sensor, is a device that detects angular motion of a body around one or two axes orthogonal to its spin axis by using a high-speed rotating rotor whose angular momentum interacts with a surrounding housing referenced to inertial space. Devices that detect angular motion by other principles but perform the same function are also called gyroscopes.

Origin of the Name

The name has historical roots. In 1850 the French physicist J. Foucault investigated Earth rotation and observed that a rapidly spinning rotor maintains the orientation of its rotation axis due to inertia. He combined the Greek words gyro (rotate) and skopein (to look) to coin the term "gyroscope".

Early gyroscopes were simple: a fast-spinning rotor mounted in a gimbal. The rotor maintains its direction due to inertia, while the surrounding gimbal rings change orientation as the device moves. Those three gimbal axes correspond to the three axes in a three-axis gyroscope: the X, Y, and Z axes. The three axes together detect motions in three-dimensional space, and various methods read the indicated directions and transmit the signals to a control system. The primary function of a gyroscope is therefore to measure angular velocity.

Basic Components

From a mechanical standpoint a gyroscope can be approximated as a rigid body with a gimbal support that allows three degrees of rotational freedom about a fixed point. More specifically, a rotor or flywheel that spins rapidly about a symmetry axis is called the gyroscope rotor. Mounting the rotor in a gimbal frame that gives the spin axis angular freedom produces a gyroscopic instrument.

The basic parts of a gyroscope are:

- Rotor: Driven to high speed by methods such as synchronous motors, reluctance motors, or three-phase AC motors. The rotor speed is typically treated as approximately constant.

- Inner and outer frames (gimbals): Provide the required angular degrees of freedom for the spin axis.

- Ancillaries: Torque motors, signal sensors, and other accessories.

Principle of Operation

Gyroscopes detect angular velocity. Their operation is fundamentally related to the Coriolis force.

When an object moves linearly in a rotating reference frame, the object experiences a transverse force and transverse acceleration. A common large-scale example is tropical cyclone formation: Earth rotation coupled with atmospheric motion and tangential forces leads to cyclonic rotation, and rotation directions differ between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.

In practical gyroscopes the rotor and frame form a compact assembly. A perfectly balanced, nonrotating gyroscope would not differ in principle from a rotating one, but in practice imbalance requires rotation to maintain stability. Gravity affects unbalanced gyroscopes: the heavier end tends downward and the lighter end upward. When an external force acts on a rotating gyroscope, the point on the rotor where the force is applied will cause the gyroscope to tilt immediately. If the potential energy at that force point is less than the rotor's rotational kinetic energy, the force point will move under rotation from a lower corner toward a higher corner, with residual potential energy driving further motion when the force point reaches the higher position.

Two Main Dynamic Properties

The two primary dynamic characteristics of a gyroscope are rigidity in space (inertia or rigidity) and precession. Both are consequences of angular momentum conservation.

Rigidity in Space

When the rotor spins at high speed and no external torque is applied, the gyroscope's spin axis maintains a fixed orientation in inertial space and resists forces that try to change its axis. Rigidity improves with larger rotor moment of inertia and with higher rotor angular velocity.

Precession

When the rotor spins and an external torque acts on one gimbal axis, the gyroscope will rotate around the orthogonal gimbal axis. In other words, a torque about the outer frame causes motion about the inner frame axis, and vice versa.

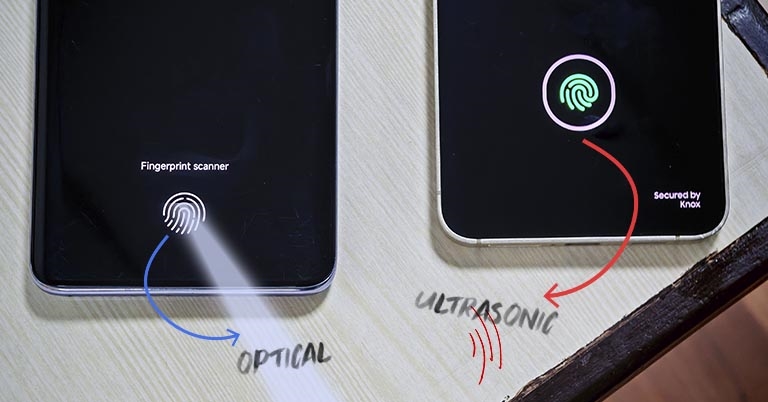

Gyroscope vs. Accelerometer

Although both sensors are used for motion sensing, the main difference is that accelerometers (gravity sensors) measure linear acceleration and gravity-related displacement, while gyroscopes measure angular velocity. Accelerometers typically provide sensitivity along up to three axes; gyroscopes provide full rotational sensing and can detect orientation changes around all axes. They operate at different levels of motion sensing and are complementary rather than interchangeable.

Common Uses in Mobile Devices

You may wonder what a gyroscope does in a smartphone. Typical uses include:

- Navigation: Gyroscopes have long been used for navigation. Combined with GPS, they improve positioning and orientation performance. Many professional handheld GPS devices include gyroscopes, and smartphone navigation with appropriate software can approach the capability of navigation instruments used on ships and aircraft.

- Image stabilization: Gyroscopes can work with cameras to provide optical or electronic image stabilization, improving photo and video quality.

- Gaming input: Gyroscopes can provide precise tracking for flight, sports, and first-person shooter games by monitoring hand motion and enabling intuitive controls such as screen rotation and steering in racing games.

- Input device: A gyroscope can act as a three-dimensional pointing device, similar to a spatial mouse; this overlaps with gaming use cases.

- Augmented reality: Gyroscopes are essential for many augmented reality functions because they deliver fast orientation updates that complement position sensing.

Applications in Aerospace and Navigation

Gyroscopes were first used in marine navigation and later found wide application in aviation and space. Beyond serving as display instruments, gyroscopes are key sensors in automatic control systems, providing signals such as heading, level, attitude, velocity, and acceleration. These signals enable pilots or autopilots to control aircraft, ships, or spacecraft along prescribed trajectories. In missile, satellite launcher, and space probe guidance, gyroscope signals are used directly for attitude and trajectory control. As precision instruments, gyroscopes also provide accurate orientation references for ground installations, tunnels, underground railways, oil drilling, and missile silos. Their application range is therefore broad and important in defense and civil sectors.

Applications in Consumer Electronics and Automotive Systems

Gyroscopes expanded the interaction modalities of consumer electronics. After keyboards, mice, and touchscreens, gyroscopes enabled gesture input and, with sufficient accuracy, even electronic signatures. They help smartphones provide intelligent orientation-aware services and sensing.

In addition to smartphones, many modern vehicles use microelectromechanical gyroscopes. High-end cars may contain 25 to 40 MEMS sensors distributed across the vehicle to monitor subsystem status and provide information to onboard computers, improving vehicle control and safety.