Overview

This article explains how state actors can deny potential, known, and unknown adversaries access to protected areas, resources, or facilities using unmanned aerial systems (UAS) and other air assets.

Key concepts

A2/AD (anti-access/area denial) is primarily used to prevent or restrict hostile forces from deploying into an area of operations.

Anti-access: measures to deny an adversary the ability to enter or operate in or near contested areas.

Area denial: measures to limit an adversary's freedom of maneuver once inside the area of operations.

Integrated air defense systems (IADS) are a core component of many A2/AD strategies.

Examples of existing and emerging A2/AD capabilities

- Layered integrated air defense systems (IADS), including modern fighters and attack aircraft, fixed and mobile surface-to-air missiles, and coastal defense systems

- Cruise and ballistic missiles launched from air, sea, and land platforms against ground and maritime targets

- Long-range artillery (LRA) and multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS)

- Diesel and nuclear submarines armed with supersonic anti-ship cruise missiles and advanced torpedoes

- Ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) forces

- Advanced naval mines

- Kinetic and non-kinetic anti-satellite weapons and supporting space launch and space surveillance infrastructure

- Advanced cyber warfare capabilities

- Electronic warfare capabilities

- Various ISR systems across multiple ranges

- Integrated reconnaissance-strike networks covering air, surface, and subsurface domains

- Hardened, buried, and closed fiber optic command-and-control (C2) networks

- Special operations forces

Recent rise of A2/AD ideology and the associated challenges

As near-peer competitors such as China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea modernize and field multi-layered defense networks, the United States Department of Defense and other policymakers have recognized that control of the global commons will face increasing challenges. It is therefore necessary to deepen understanding of the A2/AD concept to develop mitigations for penetrating and operating against contested defense networks. The US continues to rely on UAS for ISR, communications relay, and precision-guided munitions, which remain practical tools for addressing growing A2/AD threats. Nathan Freier of the Center for Strategic and International Studies has compiled a series of questions and answers explaining why the A2/AD concept remains central to military planning.

From a strategic perspective, access challenges may manifest in political, economic, and military forms. If such challenges adversely affect the security and prosperity of the US and its partners, or the stability of the international system and freedom of transit through the global commons, coordinated responses are required to restore access. By definition, such responses often involve military force (Freier, 2012).

Strategic and operational implications

The US military has unique responsibilities for ensuring access across the spectrum from peacetime presence to major combat operations. In conventional scenarios, maintaining credible deterrence in key regions preserves security and provides a platform to expand presence as tensions rise. If war occurs, US forces will face A2/AD challenges arising from both intentionally designed adversary capabilities and unstructured lethal instability. In many cases, forward-deployed forces alone will not be sufficient to overcome lethal or fundamentally disruptive A2/AD challenges. Future operations will require projecting power across substantial strategic and operational distances, and A2/AD threats complicate that ability (Freier, 2012).

Anti-access challenges

Anti-access measures aim to keep US forces out of a theater or prevent effective use and transit of global commons. These measures may begin with political and economic exclusion, progressing to military actions that deny basing, transit, or overflight. Lethal A2 capabilities include long-range systems such as ballistic missiles, submarines, WMD, and offensive space and cyber assets. Less technical but still significant A2 methods include terrorism or proxy warfare designed to open additional fronts and impose political costs (Freier, 2012).

Area denial challenges

Area denial threats are the most significant barriers to entering and operating within a theater in the near to mid term. Every contingency involving air, maritime, or ground forces must overcome substantial AD obstacles. Lethal AD threats manifest at close ranges and accumulate as US forces penetrate contested areas, limiting freedom of maneuver and complicating efforts to achieve operational objectives. AD threats can affect all five key domains: air, sea, land, space, and cyberspace (Freier, 2012).

AD capabilities range from sophisticated to crude but effective. They include cruise and ballistic missiles, weapons of mass destruction, mines, guided rockets, mortars and artillery, electronic warfare, and short-range/man-portable air defense and anti-armor systems. The information revolution—personal computing, communications, and networking—combined with non-traditional and hybrid warfare, and the spread of precision weapons, has broadened the pool of effective AD actors. Political, economic, and information instruments combined with lethal AD capabilities create resilient challenges (Freier, 2012).

AD threats can be structured or unstructured. For example, Iran's hybrid "mosaic defense" is a structured approach combining ballistic and cruise missiles, unconventional naval forces, and hybrid ground defenses to produce a complex AD challenge in the Persian Gulf. Conversely, unstructured AD challenges may arise during chaotic interventions, where multiple competitors employ destructive AD capabilities without centralized command (Freier, 2012).

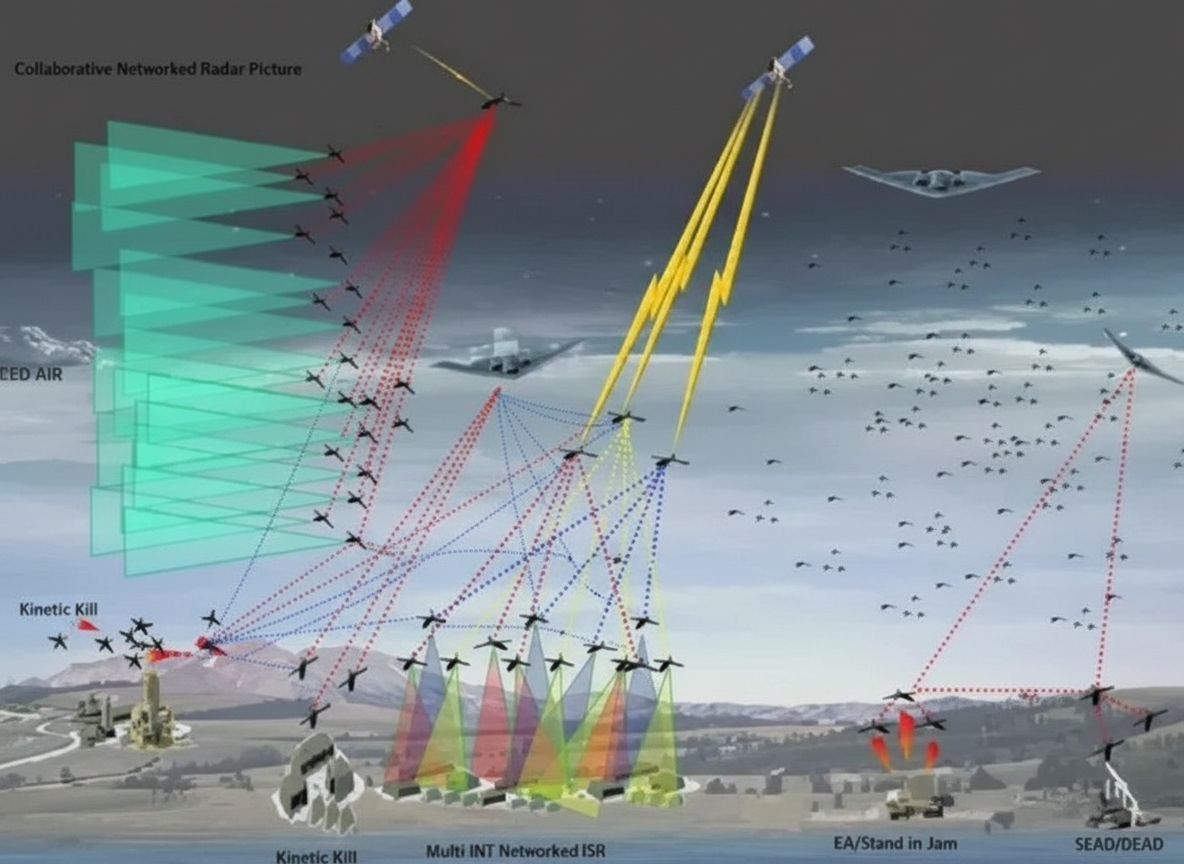

Joint operational access concept and the AirSea Battle approach

The Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC) frames how forces operate in A2/AD environments. It recognizes that forward forces may immediately face A2/AD conditions and must be able to respond effectively from the outset. One major US response concept is AirSea Battle, which seeks to integrate air and naval operations to defeat enemy sensors and strike systems across domains. The approach emphasizes cross-domain synergy between space, cyber, air, and maritime forces and includes kinetic strikes to destroy the systems that enable an adversary's A2/AD network (US Department of Defense, 2013; Cardington, 2015).

Case study: Rising A2/AD in the Indo-Pacific

The United States has long relied on freedom of movement across the global commons. However, China has deployed an interlocking set of missiles, sensors, guidance systems, and other technologies to limit adversary operations in its coastal airspace and waters. As this program matures, China's ability to restrict hostile access has increased and extended its reach. Some analysts argue this could effectively exclude US forces from parts of the western Pacific and potentially push a denial zone out toward or beyond the so-called second island chain (Cardington, 2015).

To counter this, the US pursued the AirSea Battle approach, combining passive defense against missile attack with offensive operations to degrade the capabilities underpinning an adversary's A2/AD network. Achieving this at scale requires enhancing the ability to strike deep inland targets while operating from survivable or distant bases, tracking mobile launchers and C2 nodes, and investing in long-range platforms, unmanned strike systems, missile defense, and information infrastructure (US Department of Defense).

Integrated air defense systems (IADS)

In any major conflict, modern IADS pose major challenges to air operations. IADS modernization, combined with multi-domain advances in cyber, global C4ISR, offensive strike, and threats to allied bases, represents a significant regional denial threat. The core functions of a kill chain—indications and warning, find/fix, track, engage, and assess—remain the foundation of IADS and have matured with established processes and equipment.

Advances in battle management: Over the past decade, adversaries have significantly improved global C4ISR capabilities and integrated diverse sources into a fused C4ISR infrastructure supporting IADS. This operational handling of global data presents obstacles to US airpower and air operations.

Advances in weapon systems: Since 2010, IADS modernization has included long-range A2/AD weapons supplemented by layered tactical systems. These modern weapon systems threaten many aspects of US counter-IADS and suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) capabilities, focusing on denying airborne ISR and increasing threats to 4th/5th generation aircraft, cruise missiles, precision munitions, and UAS.

Emerging vulnerability gaps

The following technologies and concepts are developing and could have major impact in the future, though they are not yet fully integrated or operational:

- Hypersonic defense

- Network-integrated defense systems

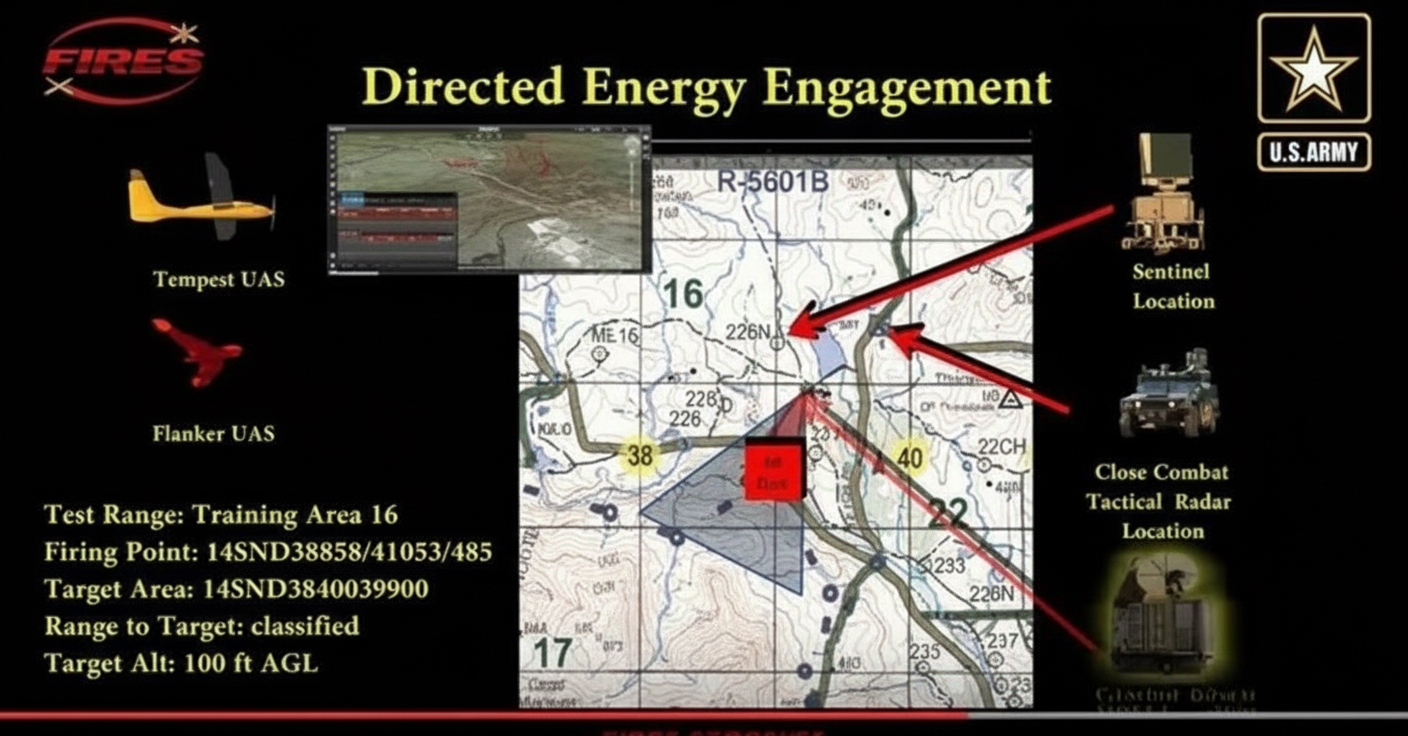

- Modern directed-energy weapons for tactical defense against airborne platforms

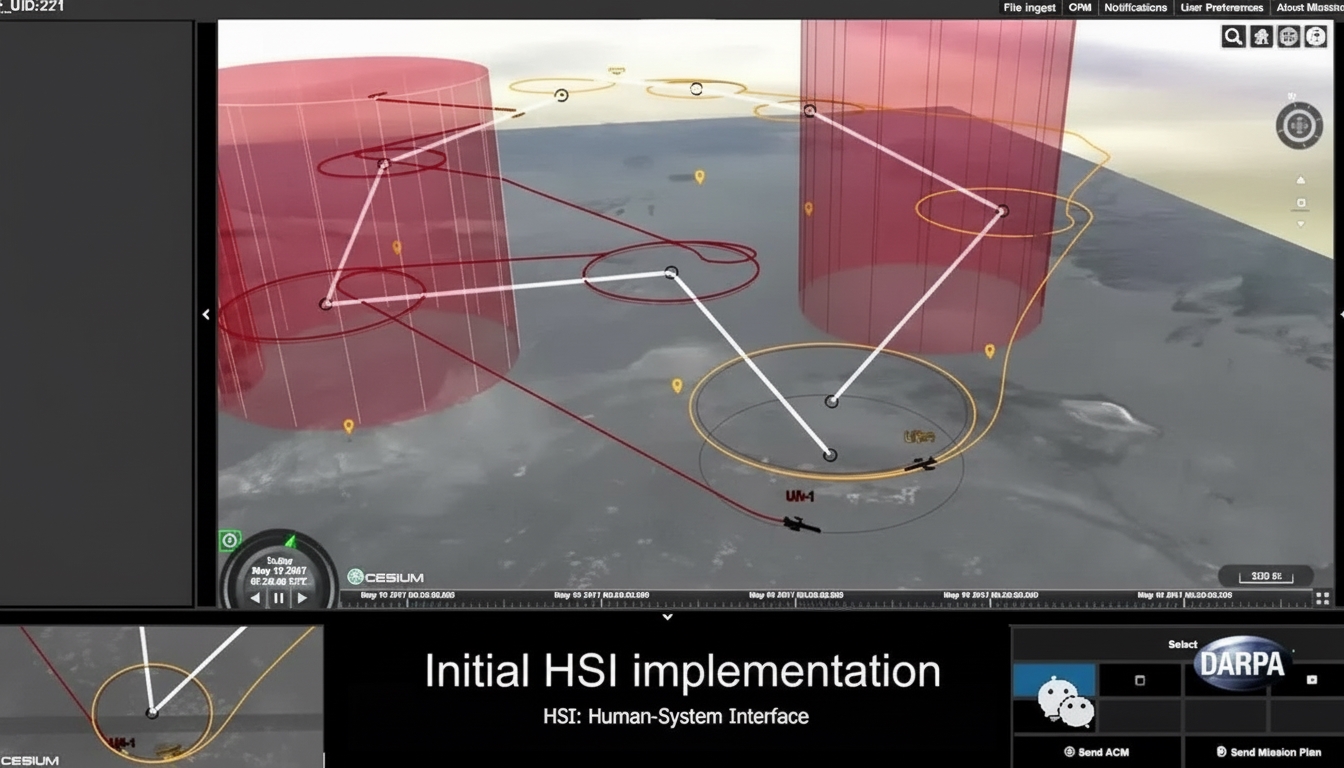

- Full integration of big data, artificial intelligence, and mature networked IADS operations

Although adversary IADS capabilities advance and pose threats to air superiority, many systems still exhibit significant vulnerabilities, such as C4I dependencies and centralized processes, which create opportunities for countermeasures (NASIC, 2019).

Russian A2/AD case study

Russia has deployed advanced A2/AD capabilities including long-range precision air defense, fighters and bombers, coastal anti-ship assets and ASW, medium-range mobile missile systems, new quiet submarines with long-range land-attack missiles, anti-space, cyber, and electronic warfare weapons. WMD assets in the Black Sea, Kaliningrad, and parts of Syria have altered the operational environment. Continued modernization through the 2020s is expected to make the battlefield increasingly complex, creating strategic buffers that affect NATO operations across high north, Baltic, Black Sea, and eastern Mediterranean regions (Bush, 2016).

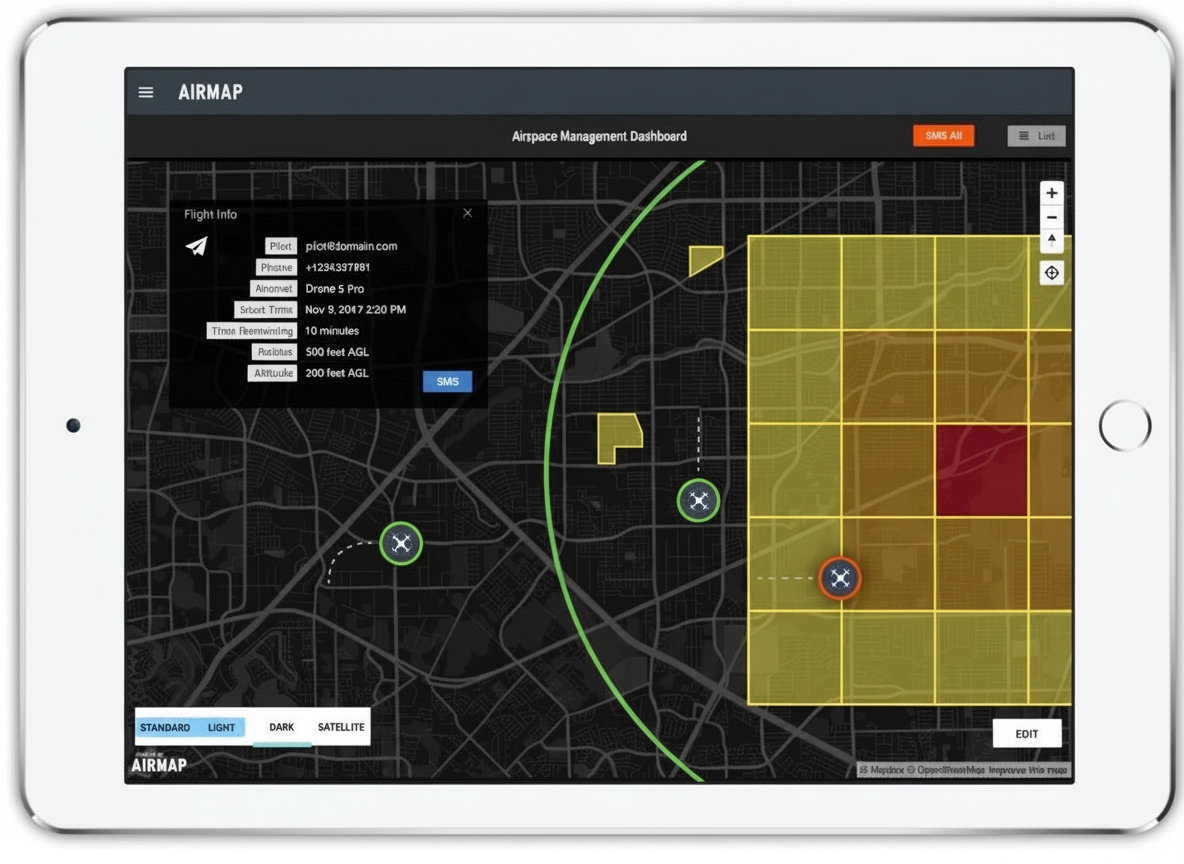

Current civil C-UAS A2/AD applications

As demand grows for localized defenses against unauthorized UAS, private companies have developed systems to detect, track, and defeat commercial drones in restricted airspace. Solutions have been deployed to protect large stadiums, public gatherings, domestic infrastructure, and prison facilities. These systems enable local authorities and agencies to interdict intruding drones that may carry contraband or pose other risks.

Conclusion

A2/AD and IADS are central concerns for defense planning. Counter-UAS (C-UAS) considerations and technologies are part of modern layered defenses against airborne intrusion. While UAS continue to operate in political gray zones focusing on access and intelligence, governments and militaries pursue non-kinetic and kinetic means to detect, deny, and engage these systems. C-UAS practitioners must understand the unique challenges posed by rapidly moving systems with increasing standoff ranges and recommend effective countermeasures that comply with applicable international and domestic laws to protect the public.

Longer-term innovative thinking will be increasingly important. Advances such as hypersonic vehicles potentially delivered by UAS will drive demand for more dynamic, integrated defense networks and faster decision cycles.