Overview of Microwaves

Like lasers, microwaves are a form of electromagnetic radiation. Their wavelengths are much longer and their frequencies much lower than visible light. Red light has a wavelength of about 0.7 μm and a frequency of roughly 4×10^14 Hz. By contrast, microwaves have wavelengths on the order of 1 cm and frequencies around 10^10 Hz, or 10 gigahertz (GHz).

Most microwave systems are designed to detect and amplify weak microwave signals.

Higher-power microwave devices intended to project energy for effects are sometimes referred to as LRAD (long-range area denial); this should not be confused with LRAD that refers to long-range acoustic devices. The most familiar amplified microwave device is the domestic kitchen microwave oven, which generates far less power than directed-energy LRAD systems.

Microwaves interact with water molecules. Electromagnetic radiation consists of photons and a time-varying electric field. Water molecules are dipolar, meaning they have ends with opposite charges and are asymmetric.

When microwaves interact with water, the oscillating electric field attempts to reorient the water molecules. In a microwave oven the field oscillates at roughly 2.45 GHz, causing molecular rotation that creates friction and transfers heat to surrounding material, thereby cooking food. High-energy directed microwave systems typically operate at higher frequencies, for example 5–80 GHz. Microwave ovens can penetrate materials to some depth because of the combination of molecule density and power, but they are not effective as weapon systems over long ranges because the beam disperses.

By contrast, military high-power active denial systems collimate energy into a beam directed at target surfaces, depositing energy at or near the skin surface where nerve endings are concentrated. Shorter wavelengths allow tighter focusing and longer effective range. Frequency is measured in hertz, cycles per second. Microwaves occupy the high-frequency radio band, typically from hundreds of megahertz to tens of gigahertz. Microwaves have many civilian uses. For example, radar uses higher-frequency, shorter-wavelength microwaves so the waves can be transmitted as a beam in a specific direction; they travel in straight lines until reflected, enabling detection of aircraft type, heading, and speed. Low radar cross-section aircraft reduce reflected energy, making detection and tracking more difficult.

How a Microwave Oven Works

Most kitchen microwave ovens operate at a frequency of 2,450 MHz. The oven directs a microwave beam into the food. Molecules in the food absorb the beam's energy, causing fats and water molecules to vibrate. That vibration produces friction and heat, raising the food's temperature. Microwave oven doors include a metal mesh embedded in the glass; the mesh reflects microwaves because the holes are too small for the wavelengths to pass, while allowing visible light through.

Definition of Microwave Weapons

Microwave weapons are devices that emit focused microwaves to damage a target. The keyword in this definition is "damage."

Although radar and microwave ovens focus microwaves on a target, their purpose is not to inflict damage. Unlike lasers, a key attribute of microwave weapons is reduced sensitivity to weather or atmospheric conditions; microwaves penetrate fog more easily than laser beams. High-energy microwave systems can have ranges of tens to hundreds of miles under appropriate conditions. These weapons can harm humans, electronic systems, and fuel. For example, exposure to high-energy microwave pulses has been associated with neurological symptoms in incidents such as the so-called Havana syndrome and earlier embassy incidents.

Electronic systems exposed to high-energy microwave pulses may suffer catastrophic failures, even if powered down or disconnected. Microwave pulses induce surge currents in circuits, causing damage. High-energy microwaves can also heat and damage fuels on vehicles, missiles, or other platforms. Like laser weapons, directed-energy microwave systems will continue to have effects as long as sufficient power is delivered. A shared advantage of directed-energy systems is the potential to replace conventional munitions in some roles, reducing the logistical and safety burden of storing and supplying explosive ordnance.

US Microwave Weapons

Personnel-Targeting Microwave Weapons

Personnel-targeting microwave systems fall into two broad categories: neuromodulation-type microwave systems and systems that produce perceived auditory sensations.

Neuromodulation-Type Systems

These systems aim to affect the human nervous system, often targeting the brain. Projection of low-frequency microwaves at humans is an example of a neuromodulation-type approach. While nonlethal in some uses, such exposure can potentially lead to lasting neurological injury. Research into effects on nonhuman primates has been conducted under classified and unclassified programs.

One line of research explored whether cells use electromagnetic signals for intercellular communication and whether external electromagnetic fields can modulate those processes. Historical studies proposed that external EM radiation could activate, overwhelm, or confuse biological processes; such nonthermal effects were investigated in earlier projects.

Biological-Effect Microwave Systems

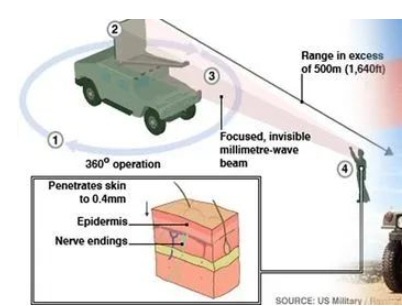

These systems can provoke various physiological responses, such as skin irritation or the perception of loud sounds. The U.S. military developed and deployed an "active denial system" that projects a strong electromagnetic beam perceived as an intolerable sudden heating sensation at the skin surface, causing targets to instinctively move away. The system output was reported at around 95 GHz, with an effective range on the order of 1,000 m. The military characterized the system as a nonlethal capability and reported limited medical incidents among exposed personnel during testing and deployment.

Microwave Auditory Effect Weapons

Some microwave systems exploit the microwave auditory effect, causing individuals to perceive sounds. Commercial and military research produced devices intended for crowd control that can cause perceived loud, painful noises. These systems may also be associated with other physiological effects, potentially including balance disruption, fever, or seizures in susceptible individuals. The basic mechanism described in patents involves slight heating of air- and fluid-filled structures in the inner ear when the head absorbs microwave energy; the resulting thermal expansion produces pressure waves interpreted by the auditory system as sound. Modulation of the microwave signal can shape the perceived audio, including speech. Patents and associated disclosures describe how such systems are constructed and operated; patent secrecy laws can limit public disclosure of operational details.

Knowledge of these capabilities is relevant because sensory disturbances such as hearing phantom sounds are sometimes interpreted as psychiatric symptoms. Awareness of the microwave auditory effect means that those experiencing such sensations could be victims of directed electromagnetic exposure rather than suffering from a primary psychiatric disorder.

Electronic Attack Using High-Power Microwaves

Microwave pulses can damage electrical and electronic systems. One program described guiding a high-power microwave payload on a cruise missile to produce sharp pulses that disable targeted electronics, enabling selective high-frequency radio-wave strikes on multiple targets during a single mission. Such systems aim to destroy electronic subsystems rather than merely interfere with them. If deployed, a weapon that physically destroys electronics would be a significant electronic warfare capability because it could permanently render adversary command centers, computers, and communications inoperative.

Directed-energy systems, including microwave and laser systems, are being evaluated for shipboard and air defense roles. Microwaves are generally less sensitive to atmospheric turbulence than lasers, making microwave systems more suitable as all-weather weapons for countering small boats and unmanned aerial systems (UAS). High-power microwave beams can disrupt or damage guidance and control electronics of drones and can affect multiple targets in a swarm situation.

Combining microwave and laser systems can reduce dependence on projectile-based close-in weapon systems and costly short- to medium-range missiles, providing sustained defensive effects as long as the platform supplies power. Directed-energy solutions may offer lower per-engagement costs compared with missiles, subject to power availability and system design trade-offs.

Russian and Chinese Microwave Capabilities

Open-source reporting and demonstrations suggest several nations have developed or pursued microwave-based systems. Russia has been reported to demonstrate microwave guns claimed to defeat drones and incoming missiles at several kilometers in range. Details often remain limited due to secrecy, and capabilities reported in public demonstrations may be exaggerated. Historical and recent programs in Russia have explored point defense and electronic countermeasure systems intended to affect aircraft and radar.

Defensive design against high-energy electromagnetic environments includes radiation-hardened electronics and system-level shielding. Nuclear detonations and other high-radiation environments can generate electromagnetic pulses that damage unprotected electronics. Systems intended to operate in such environments require hardened components and shielded interconnects. Faraday cages and continuous metal enclosures are common engineering solutions to reduce penetration by microwaves and EMP, though shielding design must account for penetrations, seams, and cable routing.

Counter-UAS Detection and Defeat

UAS have become widely used for civilian and military purposes, including imaging, delivery of medical supplies, intelligence collection, and tactical support. Their low cost and availability make them likely tools for malicious use and a growing risk to protected airspace and critical infrastructure.

Early warning is critical for effective counter-UAS (CUAS) measures. Many commercial CUAS systems focus on disrupting the radio link between the ground controller and the UAS. Reliable detection of the UAS is the first step. Enhanced CUAS solutions detect and classify commercial UAS signals, determine direction and approximate location of the UAS and operator, and apply countermeasures to break the control link.

Common UAS control schemes use frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) or Wi-Fi (WLAN) links. Downlink video or telemetry often uses FHSS, wideband, or WLAN signals. Detecting these radio-control signals requires sensitive antennas and monitoring receivers. Under ideal conditions, commercial RC links can be detected at several kilometers.

CUAS systems frequently use radar sensors for detection, which require line of sight to the UAS. Other sensors such as acoustics have range and environmental limitations. Monitoring the RC link can detect a UAS even during preflight checks when RC signals are active, providing earlier warning. Determining the RC signal bearing enables security personnel to locate and apprehend the operator.

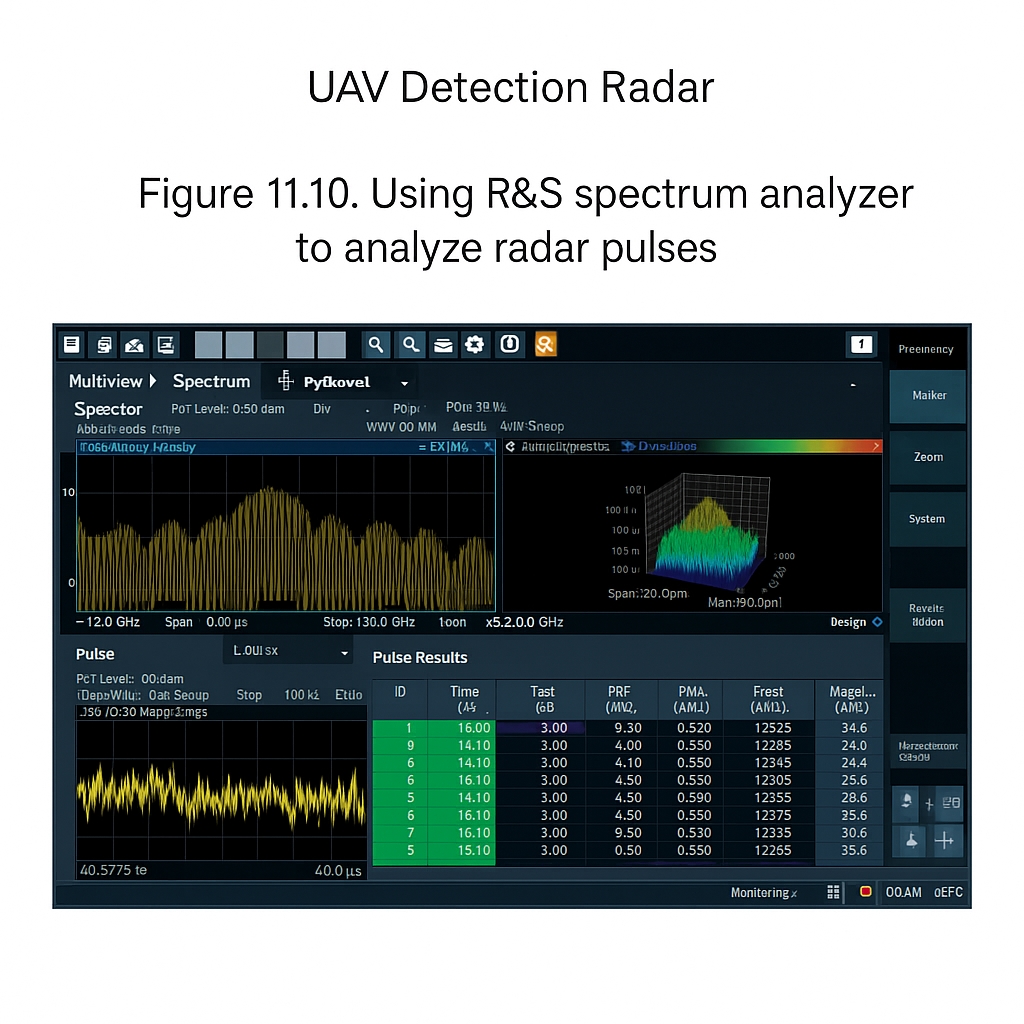

Detecting small, slow, and low-flying UAS is challenging for radar. Radar sensors must scan quickly with high sensitivity, suppress clutter and false alarms from birds, and reliably separate UAS from ground returns. Key radar design considerations include operating frequency, scan coverage and revisit time, resolution and environmental factors, and classification capabilities.

Frequency selection balances propagation efficiency, terrain, environment, desired detection range, and minimum detectable radar cross section. Many applications require 360-degree azimuth coverage and rapid refresh rates to monitor volumes and classify contacts for countermeasure initiation. Integrating optical or acoustic sensors for classification requires accurate range, azimuth, and elevation information, often demanding complex 3D capability. Microwave signal generator specifications such as output power, antenna patterns, spectral emission masks, interface performance, and phase noise of phase-locked loops are relevant to subsystem performance.

RC-Based Detection and Defeat

To detect FHSS-controlled UAS using RC signals, CUAS systems compare measured signals to a signature library. Automatic on-line analysis can identify parameters such as hop length, symbol rate, and modulation type to classify the UAS. Systems can then employ intelligent, low-power countermeasures that selectively disrupt the detected FHSS uplink, forcing the UAS to fail safe. For WLAN-controlled UAS, systems may use directional WLAN antennas to obtain bearing information and interfere with the WLAN link between controller and UAS.

Some CUAS solutions use barrage jammers that emit across a wide band, which requires higher output power and indiscriminately blocks all active transmissions in the band, not only the UAS control signals. In addition to detection and disruption, CUAS systems should provide direction-finding information for both the uplink RC bearing and the downlink telemetry or video bearing.

For reliable detection, the RC signal strength at the CUAS receiver must be at or above the receiver sensitivity or minimum SNR. SNR depends on the ambient RF environment and fluctuates. A cluttered RF environment reduces detection range. To classify UAS types, the CUAS receiver must capture signals at the minimum Rx level specific to the UAS type and the modulation scheme. Real-world trials often show vendor range claims are optimistic; actual detection and disruption ranges depend on transmitter power, antenna placement, terrain, and local RF noise.

To maximize detection range in practice, the CUAS receive antenna should be elevated, the propagation path between RC transmitter and CUAS receiver should have favorable dielectric properties, and the first Fresnel zones should be unobstructed. Low ambient RF noise, short antenna cables, and high-gain directional antennas increase detection capability.

CUAS Deployment Considerations

CUAS systems must be tailored to each application environment to achieve required detection and disruption ranges. Published vendor distances indicate how the system can be optimized for specific deployments. Determining acceptable detection and response timelines depends on how much reaction time is needed and the actions planned after detection, such as activating jammers or deploying security personnel to locate the operator.

Conclusion

From consumer appliances to crowd control, from aircraft detection to counter-UAS, microwaves play a significant role across many domains. Microwave systems can both protect and disrupt. All CUAS systems are constrained by physical laws: detection range depends on the relative positions of RC transmitters and CUAS receivers, RC transmit power, and physical and RF environmental factors. Disruption range depends on relative positions, jammer power, and environmental conditions. The required detection and disruption ranges depend on the intended application and must be carefully defined and planned prior to deployment.