Introduction

In recent years, small unmanned aerial systems (small UAS) have played a notable role in modern conflicts. In local wars such as the Russia–Ukraine conflict and the Nagorno-Karabakh fighting, systems like the Shahed-136 and the Harop loitering munition have proven effective due to low cost, operational flexibility, and difficulty of countering. The U.S. military began prioritizing counter-UAS efforts around 2010, developing new equipment and refining tactics through exercises and operations, and has built substantial capability against small UAS threats.

1. Threats from Small UAS

The U.S. military classifies UAS by weight, altitude, and speed into five tiers from low to high. Tiers 1, 2, and 3 fall within the small UAS category. These systems typically weigh less than 600 kg (1320 lb), operate below 5,490 m (18,000 ft), and fly below 463 km/h (250 kt).

Compared with crewed aircraft and larger UAS, small UAS offer several advantages: lower cost, allowing use as expendable assets for decoy or suicide missions; reduced training requirements, enabling rapid operator throughput and faster operational tempo; minimal infrastructure needs, since they do not require runways, booster launchers, large command nodes, or extensive communications chains; and mission versatility, performing intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, strike, and battle-damage assessment roles. Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning enable multiple small UAS to operate as swarms, compensating for limited per-aircraft payload and increasing overall combat effectiveness.

Operational use in recent years shows small UAS can achieve significant effects even if they rarely alone determine campaign outcomes. In 2019 Houthi forces used 10 drones to attack two Saudi Aramco facilities, temporarily reducing oil output. In December 2022, Russian forces used Shahed-136 drones to strike infrastructure in Kharkiv, Lviv, and Odesa, degrading opponent energy supplies. As formation-control technologies mature, swarms are growing in size and military potential, increasing the threat.

2. U.S. Strategic Deployment Against Small UAS

In the early 21st century, U.S. forces focused on counterterrorism and irregular warfare in the Middle East, investing in UAS and reducing air-defense forces, which weakened overall counter-small-UAS capability. During the 2010s the U.S. reassessed the threat and issued strategies and organizations to address it.

- April 2010: U.S. Army released a UAS roadmap analyzing counter-UAS trends for the 2030s and beyond.

- July 2013: The Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization staged its first non-classified counter-small-UAS exercise in California.

- April 2016: U.S. Air Force published a report on small UAS flight planning and predicted counter-UAS development over the next 20 years.

- May 2016: U.S. Army released its first operational framework to coordinate joint counter-UAS efforts.

- December 2017: Congress passed the annual National Defense Authorization Act granting limited authorities to the Department of Defense and the Department of Energy for counter-UAS activities.

- November 2019: The Secretary of Defense designated the Army to lead joint force counter-small-UAS acquisition and development.

- January 2020: The Army stood up the Joint Counter-small UAS Office (JCO) to lead, coordinate, and guide DoD counter-small-UAS activities.

- May 2020: The Secretary of Defense accepted JCO recommendations to reduce 28 DoD-approved counter-UAS platforms to 7.

- October 2020: JCO and the Army Rapid Capabilities and Critical Technologies Office held an open day to discuss emerging needs, strategy, training, and transition opportunities.

- January 2021: DoD released its first counter-small-UAS strategy, drafted by JCO, emphasizing rapid innovation, synchronized solutions, and partner cooperation.

- April–September 2021: JCO held industry demonstrations focused on low-collateral intercept systems and ground/handheld defenses.

- April 2022: JCO hosted a demonstration centered on airborne and ground-based microwave systems.

- June 23, 2023: JCO conducted a fourth industry demonstration, including Raytheon testing solutions against swarms of more than 30 drones.

- Planned for June 2024: JCO intends to run a fifth industry demonstration to test counter-UAS responses against swarms of up to 50 drones.

3. U.S. Operational Patterns for Countering Small UAS

The U.S. military divides counter-UAS operations into offensive and defensive patterns. Offensive actions aim to neutralize adversary UAS at the source by attacking ground control stations, communications gear, logistics, and launch/recovery equipment to prevent launch or sustained operations. Defensive actions focus on concealment and camouflage to avoid detection and, when a UAS is detected, on soft- or hard-kill measures to render it ineffective. Given small UAS low cost and limited infrastructure needs, offensive operations are often difficult, so U.S. forces typically employ defensive patterns.

Passive Defense

Passive defense includes camouflage and concealment, military deception, dispersed deployment, and hardening.

Against electro-optical and infrared sensors, camouflage paint, battlefield masking, and smoke are used to disrupt detection. Considering electronic reconnaissance, forces may use civilian signals to mask military signal signatures; in non-urban environments it is often preferable to power down equipment and remove signal emitters rather than attempt signal camouflage.

Military deception commonly uses decoys that mimic friendly equipment to mislead adversary UAS into attacking false targets. Decoy placement requires balance: not so distant from real assets that the adversary suspects deception, and not so close that decoy strikes cause collateral damage. Deception increases survivability, depletes adversary munitions, and can expose hostile firing positions.

Dispersal reduces concentration of personnel, materiel, and command nodes to maximize survivability. Dispersal depends on terrain: forces spread further in open desert or farmland and less in forests or urban areas where vegetation or structures provide concealment.

Hardening improves asset protection against small UAS strikes using sandbags, concrete shelters, or armor plating on buildings and vehicles. Because small UAS have limited payloads and lack heavy-kill capability, simple hardening measures can provide effective protection.

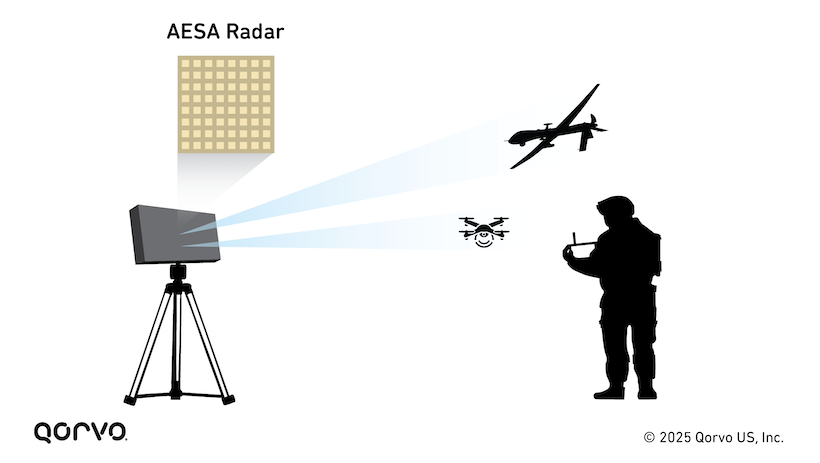

Aerial Warning

Aerial warning personnel are tasked with early detection of aerial threats near friendly forces. The U.S. combines electronic warfare systems, Ku-band RF systems, AN/TPQ-50 air surveillance radar, AN/MPQ-64 air-defense radar, and other sensors into sensor networks. Data is integrated via Link-16 and other datalinks into forward area air defense command-and-control (FAAD C2) to build a battlespace picture.

Low-altitude threats remain difficult to detect even with multiple sensor types, so aerial-warning personnel must continuously scan visually using optical equipment. Visual search techniques include vertical and horizontal scanning.

Vertical scanning involves raising the line of sight toward the sky to a maximum angle of 20° above the horizon, scanning down to the horizon, and repeating until the lateral sectors are covered. Then lower the line of sight below the horizon to 20° below and repeat until returning to the starting point.

Horizontal scanning begins by elevating the line of sight to 20° above the horizon, scanning from left to right across the sector, then lowering the elevation incrementally and scanning right to left, progressively reducing elevation until reaching 20° below the horizon.

Active Intercept

After sensors or aerial-warning personnel detect, identify, and track a small UAS, the control center decides whether to engage and selects intercept methods. Intercept options include kinetic (physical) and non-kinetic (non-physical) measures. Kinetic options use contact or destructive effects and include small arms, explosive munitions, lasers, high-power microwaves, and interception nets. Non-kinetic options rely on signal disruption, jamming, or takeover of the UAS command link and navigation signals, using RF jammers and GPS deception systems.

For kinetic measures, U.S. forces have developed light-weapon engagement tactics to create a fire intercept net where dedicated counter-UAS systems are unavailable. For loitering targets, gunners aim slightly above the drone and fire bursts of 20 to 25 rounds, adjusting aim based on impacts. Against moving targets, forces establish a firing net 50 to 200 meters ahead of the drone flight path. Concurrently, the U.S. pursues procurement of dedicated counter-UAS systems, including fire-assist sighting systems, Coyote expendable UAS, maneuverable short-range air defense (M-SHORAD) systems, and counter-indirect-fire systems. Fire-assist systems mount on individual weapons as rifle optics and compute lead based on target speed to improve hit probability. The Coyote can be fitted with fragmentation warheads or kinetic impactors to defeat hostile small UAS. M-SHORAD combines Stinger missiles, gun systems such as C-RAM or other close-in weapons, and high-energy lasers up to tens of kilowatts to counter various UAS targets. Counter-indirect-fire systems can host high-power microwave payloads like the Leonidas system to neutralize swarms within a specific sector over hundreds of meters.

Non-kinetic measures typically combine RF jamming and GPS deception and are the prevailing approach. Of the eight interim counter-small-UAS systems identified by JCO in 2020, six employed non-kinetic effects, with the other two being a command system and a fire-assist system. In operations, jammers and deception systems are directed toward hostile UAS to continuously interfere with control and navigation links, exploiting protocol vulnerabilities to sever remote control and navigation, causing loss of adversary control.