Overview

Airplane windows differ from household windows: they are small and rounded. The design responds to structural, aerodynamic, and operational requirements encountered in flight.

1. Window strength

Early aircraft flew at low altitudes and had unpressurized cabins, so the stresses on the airframe were relatively small and windows were sometimes square. As flight speeds and operational altitudes increased, aircraft perform more maneuvers and cabins are pressurized, which raises the structural load on the fuselage.

Openings in a structure concentrate stress and are the most likely locations for fatigue-related failure. Studies show that polygonal windows, including square ones, concentrate stress at the corners (a large portion of cabin pressure can focus on window corners), which can lead to material fatigue and structural failure. Circular or rounded openings distribute stress more evenly around the perimeter, greatly reducing the chance of a localized failure initiating from a single point.

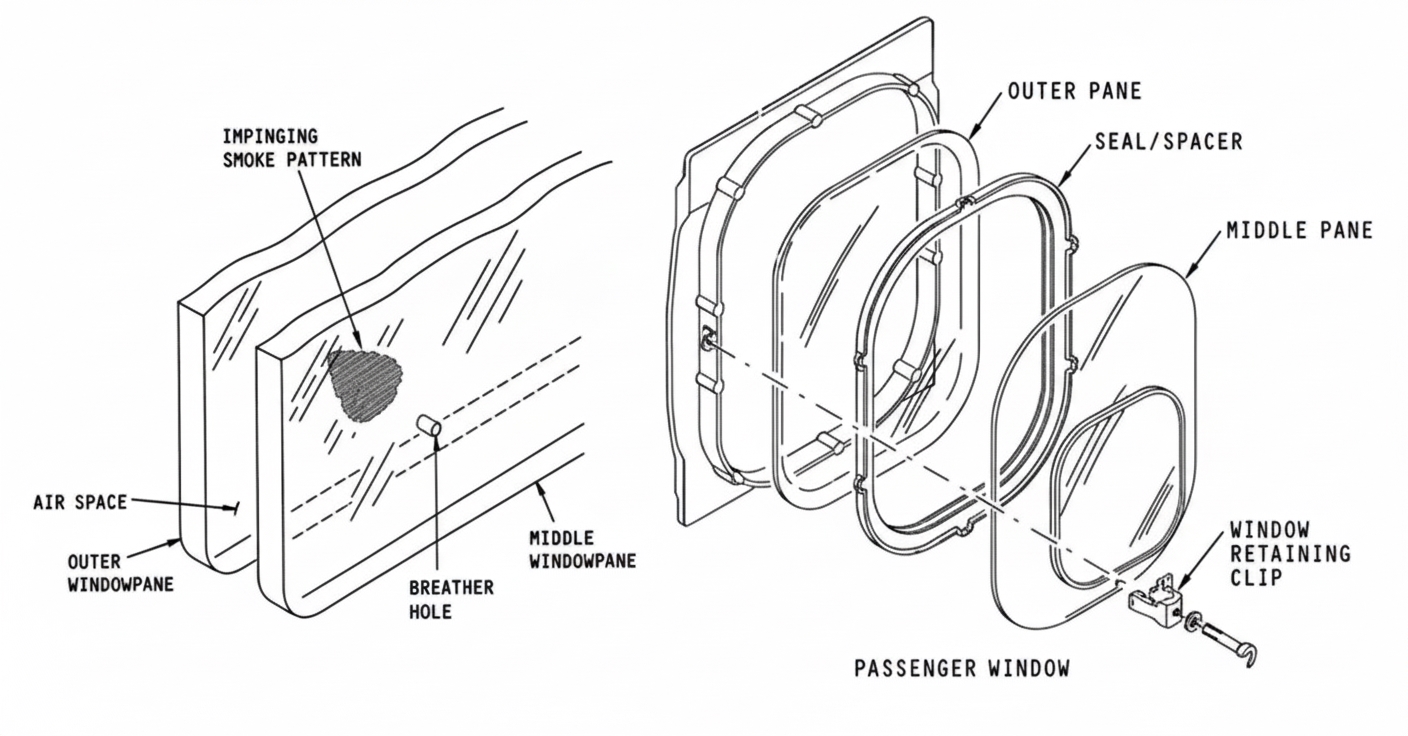

Typical aircraft windows are made of three layers of glass or acrylic with distinct roles: the outer layer bears the pressure differential between cabin and outside; the middle layer serves as a fail-safe in case the outer layer is damaged, although outer-layer breakage is rare; the inner layer protects the cabin interior and can be scratched or written on by passengers.

The small hole at the bottom of the window pane ensures the outer layer does not take an unexpected pressure impulse. This "breather" hole equalizes pressure in the cavity between window panes so that cabin pressure loads are properly transferred to the outer pane. In the event of pane failure, this arrangement ensures the outermost pane is the first to fail, helping to maintain cabin integrity and passenger safety.

2. Aircraft structure

The fuselage consists of the skin, stringers, frames, and other structural members that interlock and form a grid. Window openings are installed within that structure, so their size is constrained by the surrounding reinforcement and load paths. A notable example is the Concorde: supersonic flight imposed tighter structural requirements and denser reinforcement, so its windows were very small, roughly the size of a postcard.

3. Cost and operational considerations

Window size also reflects economic and operational trade-offs. Larger windows increase structural complexity and weight; they may require lower operating altitudes or speeds, or more expensive materials and reinforcements to meet safety and fatigue requirements. Aircraft window area is therefore chosen to balance passenger viewing needs with structural integrity, performance, and cost.