Introduction

Many people hear the word robots and imagine flashy appearances and advanced capabilities like those in science fiction. In reality, robots are engineered systems that perform tasks by combining physical structure, actuators, sensors, power sources, and computing. This article explains core concepts in robotics and how robots accomplish their tasks.

1. Robot Components

At a basic level, a human body can be described by five core elements:

- structural frame

- muscle system for moving the frame

- sensory system for receiving information about the body and environment

- energy source to power muscles and sensors

- brain to process sensory information and command motion

Robots mirror these elements. A typical robot has a movable structural frame, actuators such as motors, a set of sensors, a power source, and a computer "brain" that controls the system. Essentially, robots are engineered machines that mimic behaviors of humans and animals.

The term robot covers a wide range of machines, from large industrial robots used on factory floors to small household cleaning robots. A common practical definition used by many practitioners is that a robot should have a reprogrammable computer that can move a body.

This distinguishes robots from other moving machines, such as cars. Modern cars include onboard computers for minor adjustments, but most vehicle components are directly controlled by the driver through mechanical linkages. Robots are distinct because their computer element directly controls a connected body.

Common characteristics

First, most robots have a movable body. Some use motorized wheels, while others include many moving parts made of metal or plastic. These parts are connected by joints, analogous to human bones connected by joints.

Actuators connect wheels and shafts to the structure via transmission systems. Some robots use electric motors and solenoids, others use hydraulic systems, and some use pneumatic systems driven by compressed gas. Robots may employ any of these actuator types.

Second, robots need an energy source to power actuators. Most robots use batteries or mains power. Hydraulic robots require a pump to pressurize fluid, while pneumatic robots need an air compressor or compressed gas tanks.

Actuators are connected by wiring to a control circuit. That circuit supplies power to electric motors and solenoids and operates electronic valves for hydraulic systems. Valves direct pressurized fluid to actuators. For example, to move a hydraulically driven leg, the controller opens a valve that routes fluid from a pump into the leg cylinder. The pressurized fluid pushes the piston and rotates the leg. Robots typically use double-acting pistons so components can move in both directions.

The robot's computer can control all circuit-connected components. To make the robot move, the computer activates the required motors and valves. Most robots are reprogrammable: changing behavior involves loading a new program into the robot's computer.

Not all robots have extensive sensory systems. Few robots possess vision, hearing, smell, or taste. The most common sensing capability is proprioception, or the ability to monitor their own motion. Standard designs include slotted wheels at joints. A light-emitting diode beams light through the slots to an optical sensor on the opposite side. As the joint moves, the slots interrupt the light beam. The optical sensor reads the pattern of light interruptions and sends data to the computer, which computes the joint rotation. This mechanism is similar to basic systems used in computer mice.

These are the fundamental elements of robots. Engineers combine these elements in many ways to create robots of varying complexity. Robotic arms are among the most common designs.

2. How Robots Operate

The English word robot comes from the Czech word robota, often translated as "forced laborer." That description fits many robots: they perform repetitive, labor-intensive manufacturing tasks that are difficult, dangerous, or tedious for humans.

The most common manufacturing robot is the robotic arm.

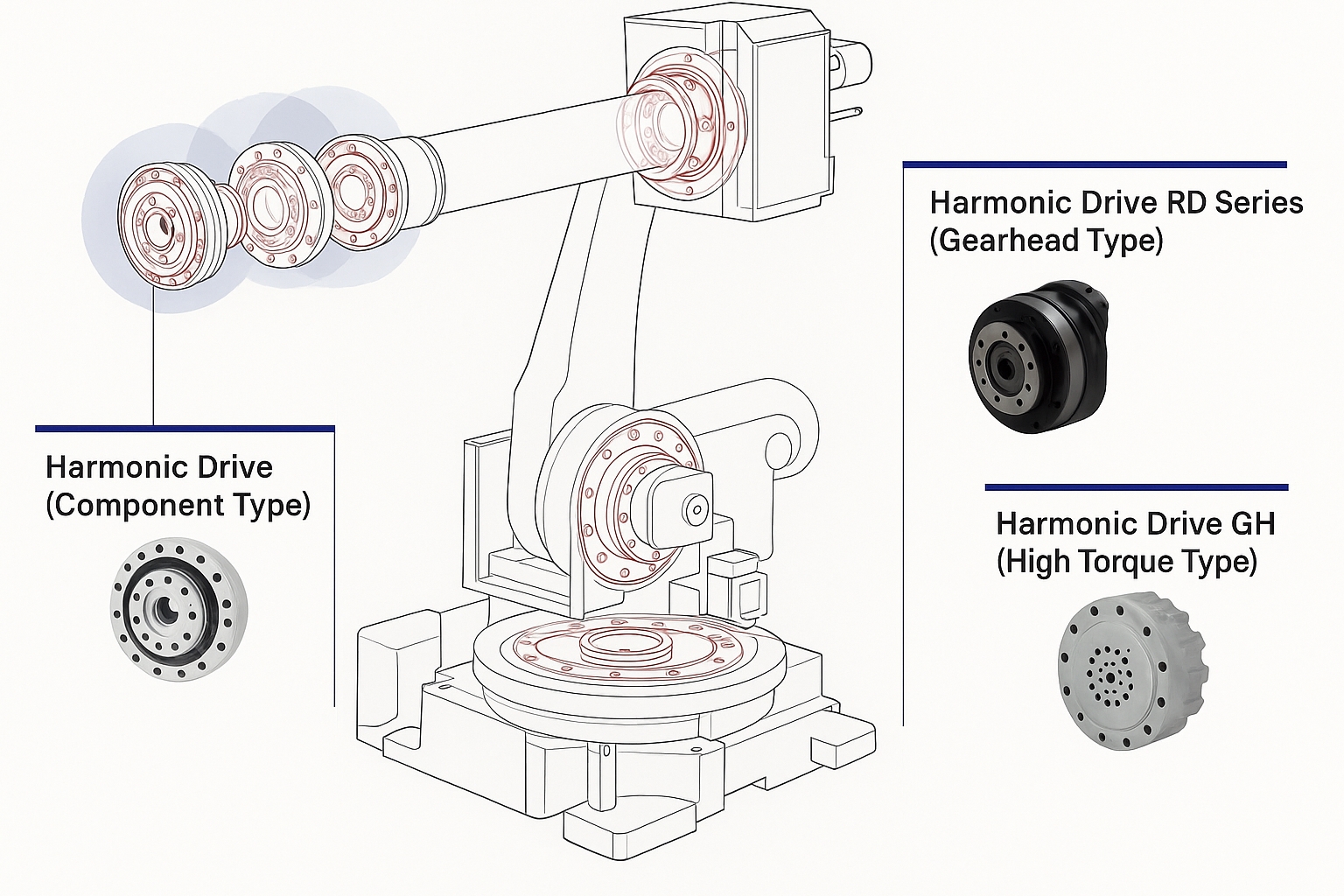

A typical robotic arm comprises seven metal segments connected by six joints. The computer controls stepper motors attached to each joint to move the arm. Large arms may use hydraulic or pneumatic actuation.

Unlike ordinary motors, stepper motors move in precise increments. This allows the computer to position the arm accurately and reproduce exactly the same motion repeatedly. Motion sensors ensure the arm moves the correct amount.

A six-joint industrial robot resembles a human arm, with analogs of shoulder, elbow, and wrist. Its "shoulder" is usually mounted on a fixed base. Such robots have six degrees of freedom, meaning they can rotate in six independent ways; by comparison, a human arm typically has seven degrees of freedom.

Robotic arms move end effectors to desired positions. Various end effectors suit different applications. A common end effector resembles a simplified human hand that can grip and move objects.

Robot hands often include embedded force sensors to report grip strength to the computer. This prevents objects from being dropped or crushed. Other end effectors include torches, drills, and paint sprayers.

Industrial robots are designed to perform identical tasks repeatedly in controlled environments. For example, a robot might tighten lids on jars on an assembly line. To teach the robot, a programmer guides the arm through the desired motion with a handheld controller. The robot stores the motion sequence in memory and repeats it for each jar that arrives on the line.

Robots are widely used in automotive assembly and semiconductor manufacturing. Their precision allows consistent drilling, fastening, and handling of tiny chips regardless of operating hours.

Designing and programming robotic arms is relatively straightforward because they operate within a limited workspace. Extending robots into the open world introduces additional complexity.

The primary challenge for mobile robots is locomotion. For movement on flat surfaces, wheels or tracks are effective. If wheel or track width is sufficient, they can handle moderate rough terrain. Designers often prefer legged designs for greater adaptability and to study natural kinematics.

Legged robots typically use hydraulic or pneumatic pistons to move limbs. Pistons attach to different limb segments like muscles attached to bones. Coordinating multiple pistons for stable walking is challenging. Balance must be maintained, so many mobile robots include inertial sensors such as gyroscopes to inform corrective actions.

Bipedal walking is inherently unstable and difficult to implement. Designers often look to animals, especially insects, for inspiration. Insects' six-legged gait provides robust balance across uneven terrain.

Some mobile robots are remotely controlled. Operators issue commands via tether, radio, or infrared signals. Remote robots, sometimes called teleoperated robots, are useful for exploring hazardous or inaccessible environments such as deep-sea or volcanic areas. Some robots operate under partial teleoperation: an operator may specify a destination but allow the robot to autonomously navigate the path.

Autonomous robots act without remote human control. They are programmed to respond to external stimuli. A simple collision-avoidance robot illustrates this concept.

Such a robot uses bump sensors to detect obstacles. Once activated, it moves roughly along a straight course. On contact, the bump sensor registers impact. The robot's program then directs it to back up, turn, and continue. By repeating this rule, the robot changes direction whenever it encounters an obstacle.

Advanced robots implement these principles in more sophisticated ways. Engineers develop improved programs and sensor suites to create robots with greater perception and intelligence. Modern robots operate effectively in diverse environments.

Basic mobile robots use infrared or ultrasonic sensors to detect obstacles. These sensors operate like biological echolocation: the robot emits a sound pulse or infrared beam and measures the reflection time. Distance to an obstacle is computed from the round-trip time of the signal.

More capable robots use stereo vision for depth perception. Two cameras provide depth cues, and image recognition software identifies object positions and categories. Robots may also use microphones and chemical sensors to analyze the environment.

Some autonomous robots work only in familiar, constrained environments. For example, robotic lawn mowers use buried boundary markers to define the mowing area, and office cleaning robots may rely on building maps to navigate between locations.

Higher-level robots can analyze and adapt to unfamiliar environments and challenging terrain. These robots correlate terrain patterns with appropriate motion strategies. For instance, a rover uses vision sensors to map the ground ahead; if the map indicates rough terrain patterns, the rover selects an alternative route. Such systems are valuable for planetary exploration.

An alternative design approach uses loose control and randomized behaviors. When such a robot becomes stuck, it moves appendages in various directions until a motion produces progress. This method relies on tight mechanical and force sensing interaction with actuators rather than a strictly programmed sequence. The approach resembles how ants attempt different paths to bypass obstacles.

3. Home-built Robots

Hobbyist robotics is an active subculture. Enthusiasts build robots in garages and workshops using commercial robotic kits, mail-order parts, toys, and salvaged components.

Hobbyist robots vary widely. Weekend builders may produce sophisticated walking machines, domestic helper prototypes, or competitive robots. Many remote-controlled combat robots are reinforced radio-controlled vehicles rather than reprogrammable robots.

More advanced competition robots are computer-controlled. For example, robot soccer teams operate without human input during matches. A central computer processes camera images of the field and, using color-based segmentation, identifies the ball, goals, and players, then issues commands to each robot.

Adaptability and modular platforms

The personal computer revolution is defined by adaptability. Standardized hardware and programming languages enabled engineers and hobbyists to build computing systems for diverse purposes. Historically, most robots were purpose-built devices optimized for a single task rather than general-purpose machines.

That situation is changing. Modular robotic development platforms provide reusable software and hardware components for common robotic functions such as target tracking, voice command recognition, and obstacle avoidance. These capabilities are not novel individually, but their integration into simple developer packages reduces engineering effort.

Typical kits include sensors, motors, a microphone, and a camera, along with mounting hardware such as aluminum frame parts and robust wheels. Some kits are priced at several hundred dollars and aim to accelerate prototyping of domestic or service robots.

4. Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is one of the most debated areas in robotics. While there is consensus that robots can perform assembly tasks, opinion varies on whether they can exhibit intelligence in a human-like sense.

Defining AI is challenging. Strong AI would replicate human cognitive processes, enabling general learning, reasoning, language, and belief formation. Robotics researchers have not achieved that level, but they have made substantial progress in narrow AI: systems that mimic specific intelligent behaviors.

Computers now solve problems within constrained domains. The basic AI workflow involves collecting facts about a situation via sensors or human input, comparing that information with stored knowledge to determine meaning, evaluating possible actions, and predicting which action yields the best outcome. The system can only solve problems framed by its programming. Chess-playing programs illustrate this approach.

Some modern robots have limited learning capabilities. Learning robots can determine whether a particular action produced the desired outcome and store that information for future similar situations. This form of reinforcement learning is typically narrow in scope. Some robots learn by imitation; in one example, researchers demonstrated dance moves to a robot, which then reproduced the moves.

Some robots have human-interaction capabilities. Kismet, developed at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, recognizes human body language and speech prosody and responds accordingly. Kismet was designed to study low-level social interactions, such as those between adults and infants, where tone and visual cues convey meaning.

Kismet and other robots from MIT use unconventional control architectures. Rather than a single central controller, low-level behaviors are handled by lower-level processors. Rodney Brooks, a project lead, argues that this models human intelligence more accurately: much human behavior is automatic and not centrally decided by conscious thought.

The real difficulty in AI is understanding how natural intelligence operates. Unlike engineering a mechanical organ, researchers lack a complete, testable model of cognitive processes. The brain contains billions of neurons and learning arises from changes in connections among them, but how these connections produce higher-level reasoning is not well understood. Neural networks appear highly complex.

Consequently, AI remains largely experimental. Scientists propose hypotheses about human learning and reasoning and use robots to test these ideas. Just as robotic design helps study anatomy and locomotion, AI research helps probe principles of natural intelligence. For some researchers, this insight is the ultimate goal. Others envision a future where humans live alongside intelligent machines that handle labor, healthcare, and communication. Some predict deeper human-machine integration, but such outcomes remain speculative.

Regardless of long-term outcomes, robots will play an increasing role in daily life. Over coming decades, robots are expected to expand beyond industrial and scientific use into everyday environments, analogous to how computers proliferated into households in the 1980s.