Overview

As vehicles become smarter, more complex, and increasingly connected, they are also more exposed to cyberattacks. The current challenge for automotive cybersecurity is keeping pace with hackers who continually develop new methods to target in-vehicle software and hardware.

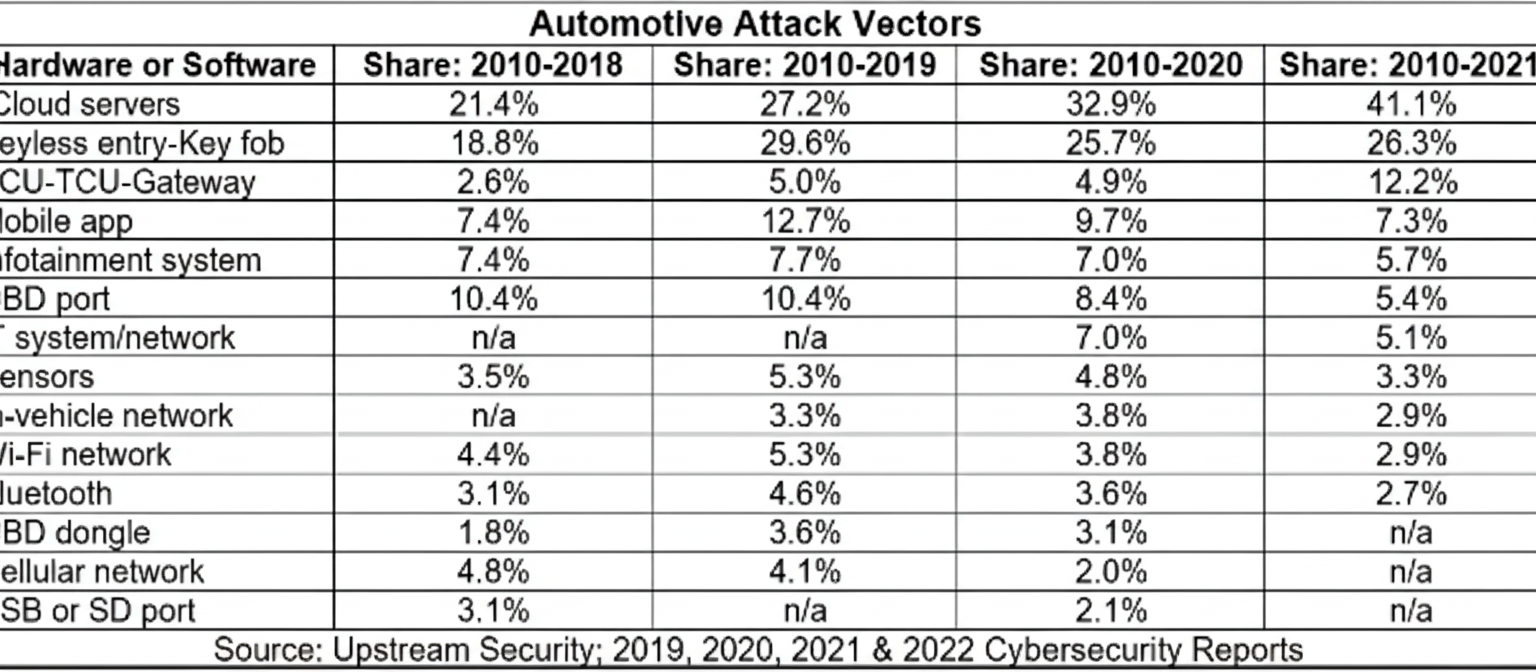

According to Upstream's 2023 Global Automotive Cybersecurity Report, deep- and dark-web activity and incidents related to application programming interfaces (APIs) increased significantly in 2022 compared with the previous year. About 63% of reported incidents were attributed to black-hat actors using a variety of attack vectors. Targets included telematics and application servers, remote keyless entry systems, ECUs, infotainment systems, mobile apps, EV charging infrastructure, and Bluetooth.

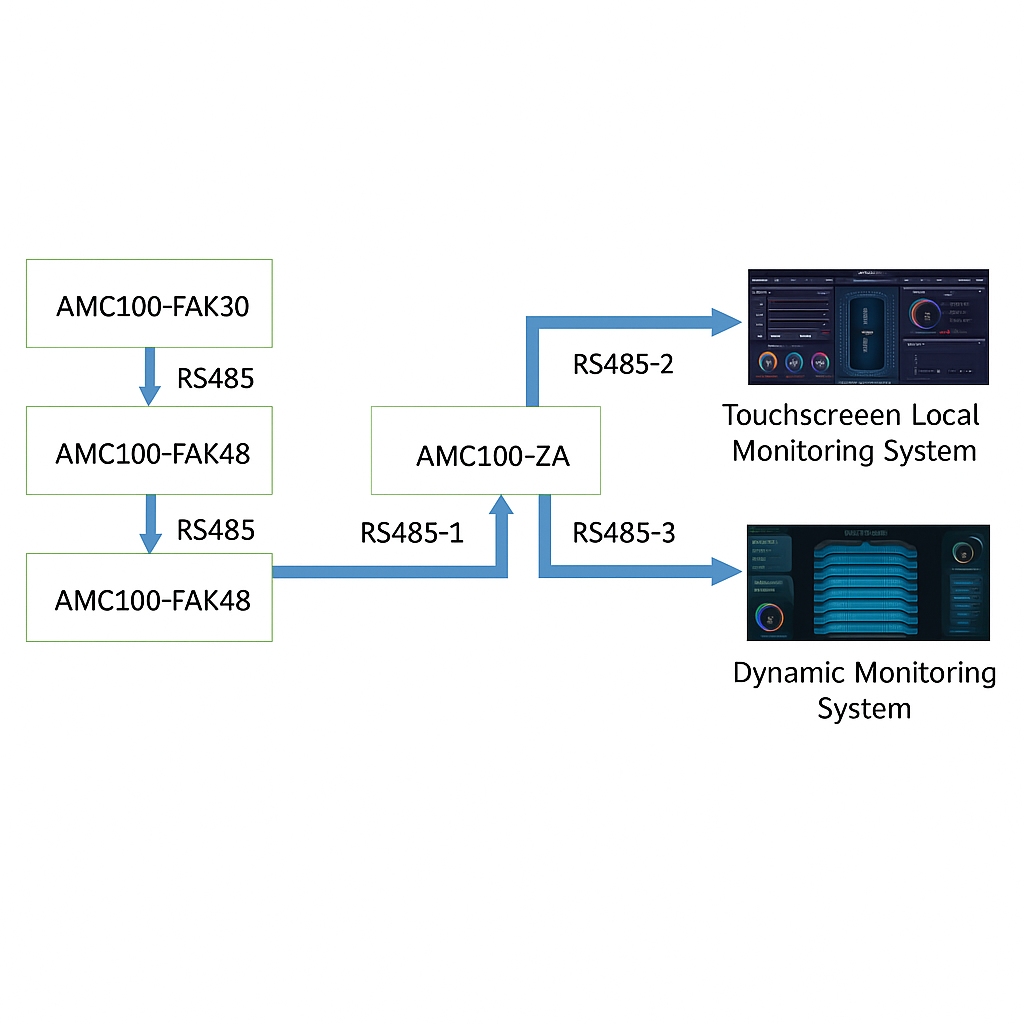

Figure 1: Impact of automotive attack vectors, 2010–2021. Source: Upstream

Historical incidents and recent trends

This is not a new problem. In 2015, two security researchers demonstrated remote control of a Jeep Cherokee, causing the vehicle to veer off the road and prompting Chrysler to recall 1.4 million vehicles. The researchers showed that cellular access to the infotainment system could be used to reach other ECUs.

More recently, insurers temporarily stopped offering policies for some Hyundai and Kia models after a surge in vehicle thefts and rising claim costs. One driver of increased thefts was the proliferation of social media videos showing how to start cars without keys. In response, Hyundai in February 2023 provided a free anti-theft software upgrade for more than 1 million Elantra, Sonata, and Venue vehicles.

With growing software content in ECUs and ADAS and more electronic hardware, vehicles are more vulnerable to attackers than ever before. Semiconductor technologies are critical to future vehicle digitization, including microcontrollers, sensors, discrete security modules, and power components. As vehicles become more digital, cybersecurity is essential both to resist threats and to ensure safe, reliable operation of advanced vehicles.

Common attack vectors

Most increased electronic content and connectivity are necessary to remain competitive. However, they also open many remote-attack avenues; today remote attacks account for roughly 90% of entry-point attacks.

Remote keyless fobs are often the most attractive target, followed by mobile phones used to connect to infotainment systems or to remotely start vehicles in cold weather. On-board diagnostics (OBD) used by dealers or mechanics are another entry point. Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and telematics networks can be accessed by attackers, and as electric vehicles gain popularity, charging ports are emerging as additional targets.

Many sensors will use wireless interfaces to report conditions such as tire pressure. Those sensors are low cost but still need protection. Consider a scenario in which a roadside attacker broadcasts a false "tire blowout" alert to cause serious disruption on a road segment. Strong, validated security is required for communications both to and within the vehicle.

On-board connectivity provides useful features such as emergency services, but it also increases risk, especially when a vehicle is connected to the internet or other networks. An attack on one system can trigger cascading effects across the vehicle.

Three principal hacker targets are communication systems (the in-vehicle networks), infotainment systems controlling audio, navigation, and other features, and remote keyless entry systems that can unlock and start vehicles without a key. Typical vulnerabilities include lack of encryption, weak authentication, and outdated software. Potential targets include mobile apps, OBD ports, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth.

Combining hardware and software security measures helps prevent vulnerabilities and detect issues in real time, for example by alerting drivers to unexpected traffic on on-chip networks or I/O systems. But this is only part of the solution.

Supply chain challenges

Robust security also requires cooperation across companies. OEMs must manage the entire supply chain to close security gaps, which increases complexity.

Every added smart subsystem increases the attack surface. Since systems inside the vehicle are interconnected, a vulnerability in one connected subsystem can chain to others. This requires close and trusted relationships between automakers, their Tier 1 suppliers, and those suppliers' vendors.

Security in the software supply chain is critical. The vehicle software stack often includes numerous vendors, some of which may have business relationships that permit or limit access to customer data.

Some OEMs are taking this challenge seriously. For example, General Motors has implemented a three-pillar approach based on industry and government best practices—defense in depth, monitoring and detection, and incident response—to protect customers. The company also participates in industry efforts such as Auto-ISAC, the Cyber Readiness Institute, and the Cyber Auto Challenge.

Mercedes-Benz has stated that higher digital integration increases cybersecurity requirements. The company focuses on proactively managing vulnerabilities and threats across each vehicle's lifecycle.

How to respond to evolving cyber threats

Building cybersecurity defenses is essential. As threats evolve rapidly, approaches range from protecting communication protocols to embedding security early in the design cycle, balancing security and cost, and adopting new security standards.

All entry points—except those that require physical access, such as OBD ports—should use secure communication protocols and centralized processes for managing security keys with a trusted root. In many cases, the same data sequence is reused between endpoints, for example in keyless-fob exchanges. Once compromised, such repetition enables attackers to access a vehicle.

For complete protection, each communication protocol needs authentication by a trusted root to ensure keys and encrypted secrets remain confidential and are handled securely. Whenever a software module is compromised, a trusted root can be used to update it to a fixed version. When hardware devices are compromised and keys are exposed, those keys can be replaced through a trusted-root-assisted process. Typically, the trusted root uses an uncompromised secret recovery key located in a hardware-protected security enclave so the vehicle can recover from network attacks.

Building security early in the design cycle

To be effective, security needs to be implemented early in the design cycle, ideally at the architecture level. Given long design cycles and fast-moving technologies, this is challenging.

Obtaining a unified security view across architecture plans is difficult because so many suppliers contribute to vehicle components. OEMs should avoid trying to reinvent foundational security mechanisms from scratch. Reusing existing technologies and mechanisms that are proven in other industries can help OEMs achieve better cost effectiveness. Elements from industrial control systems or medical-sector security mechanisms can be adapted to ensure critical components behave correctly. The automotive industry can and should rely on relevant automotive security mechanisms as well.

Security is a system-level issue involving SoCs, software, and interactions among potentially hundreds of SoCs in software-defined vehicles. Therefore, considering security during system design and conducting early threat and vulnerability analysis is essential.

Trusted domains are a known element of secure architectures. Dedicated IP allows systems to be partitioned into trusted and untrusted domains so that only trusted entities can access critical components. This can help OEMs regain control when an attack occurs, and such attacks are expected to increase.

Any compute unit inside the vehicle is a potential threat. The most vulnerable areas are places where physical connections to vehicle devices are possible, such as OBD connectors, although those attacks require physical access. Other threat types include attempts to insert malicious code during software development, exploitation through unauthorized entry points in deployed systems, and attacks targeting software update mechanisms. Development teams should identify root causes and vulnerabilities to determine appropriate mitigation steps.

Balancing security and cost

Finding a pragmatic way to implement sufficient security while keeping costs reasonable is critical.

Understanding what attackers seek is important. Attackers typically do not invest significant effort to breach the most hardened targets; they look for simple, accessible targets such as key fobs. Adversaries can reverse-engineer key fob operation to gain vehicle access and steal the vehicle or its contents. OEMs can raise the bar for common attackers by consolidating and strengthening accessible areas, making vehicles less susceptible to general attacks. Expecting OEMs to harden vehicles against all attackers to the point that no one can ever access them is unrealistic; the cost would be borne by consumers.

Standards can help establish a sufficiently strong baseline, and the automotive ecosystem is moving in that direction. For example, NIST recently selected the Ascon algorithm for lightweight cryptography. Ascon is efficient and can provide low-cost security for many automotive sensors. Using testing tools and services to validate the security of all vehicle components is important and also helps OEMs achieve ISO/SAE 21434 compliance.

Equally important are observability of communications and telemetry and certification of safety-critical elements. As security and safety become parallel priorities, security certification for on-chip network IP entering SoC development is crucial. For this reason, configurable NoC IP is being augmented with security and resilience features and validated with customers to meet ISO 26262 and ISO/SAE 21434 requirements. As the industry moves toward heterogeneous integration with smaller chiplets, a new set of security challenges is emerging.

Worst case and recovery: digital twin approach

If the best security measures are in place and a system is still breached, keys combined with a digital twin approach can be used to recover the system. This is akin to rebooting a computer, though not necessarily a complete shutdown.

Any part of a vehicle can be targeted by cyberattacks. For example, if cameras provide conflicting traffic-light states, the vehicle could be placed in a dangerous situation if it makes the wrong decision. If a human driver remains in control, the impact may be limited, but as vehicles become more autonomous these situations could be fatal.

One solution is to implement a digital twin—a digital replica of the physical vehicle that stores original functional data. When a cyberattack is detected in the field, the vehicle can be restored to a golden-standard state that recognizes anomalies and corrects vulnerabilities. Over-the-air updates can then be pushed to all fleet vehicles to ensure they are secure. Frameworks such as SOAFEE are well suited to this approach.