"Connected vehicles have inherent systemic issues, namely software and hardware vulnerabilities and backdoors. Network attacks exploiting these can directly lead to ransomware, theft, large-scale malicious vehicle control, and data leaks. If these inherent vulnerabilities and backdoors are not resolved, the system itself cannot be guaranteed secure, making it difficult to ensure data security or application security on top of system security."

— Wu Jiangxing, academician of the Chinese Academy of Engineering

Overview

As vehicle intelligence and connectivity advance, Over-The-Air (OTA) software update technology has become widely used. However, on-board software faces potential risks of data spoofing, theft, or attack during remote updates. In 2020, the State Administration for Market Regulation issued a notice strengthening oversight of automotive OTA recalls to improve connected vehicle safety.

Looking at the history of connected vehicle regulation, a 2017 Science article titled "Black box is not safe at all" highlighted safety concerns around vehicle black boxes, namely on-board diagnostic systems. The United States mandated OBD-II compliance for vehicles on sale since 1996, and the European Union implemented the European OBD (EOBD) standard from 2001.

The above standards impose certain restrictions on catalytic converters used for exhaust treatment, which are subject to regulation. (Image source: online)

Two issues stand out. First, neither OBD-II nor EOBD include dedicated security specifications, so manufacturers cannot comprehensively test the "black box." In other words, vehicle security has remained a long-term, unresolved problem for connected vehicles.

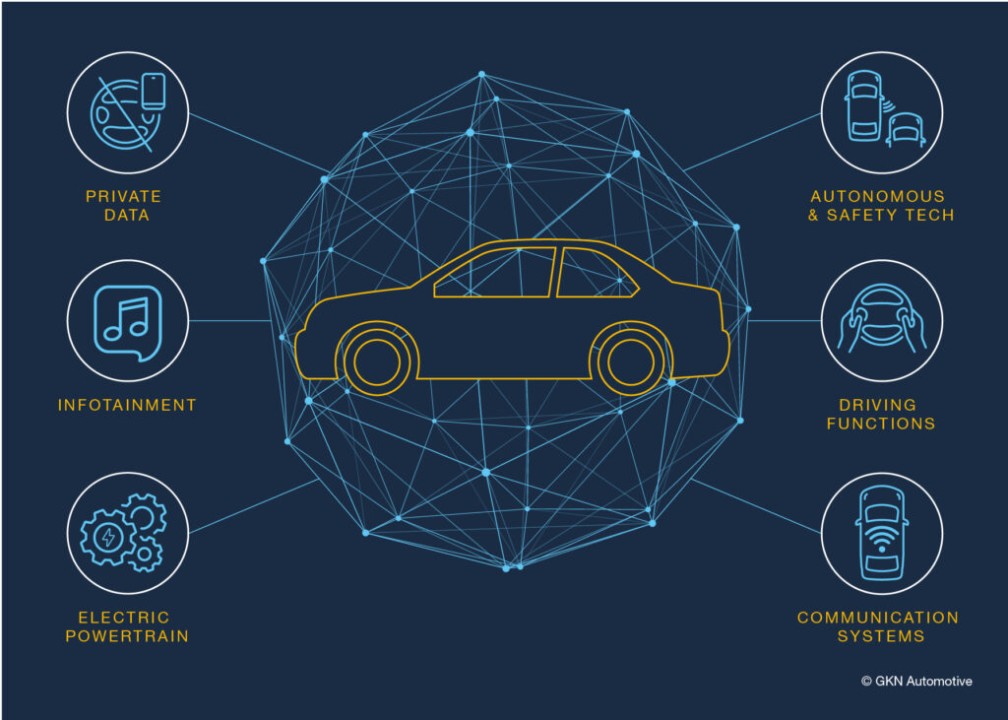

Second, with the number of electronic control units (ECUs) in a single vehicle now reaching into the hundreds, adding new features increases the attack surface. Systems with intensive information exchange—such as in-vehicle infotainment (IVI), smartphone connectivity, and remote vehicle telematics—are typically the weakest points and primary targets for attackers.

This article classifies vehicle hacking into two main categories: sensor attacks and vehicle access attacks.

Sensor Attacks

For vehicles with autonomous driving capabilities, perceiving surrounding events is one of the most critical functions. Autonomous systems typically rely on GPS, millimeter-wave (MMW) radar, LiDAR (light detection and ranging), ultrasonic sensors, and camera sensors. Below are common attack methods against these sensors and corresponding mitigations.

GPS jamming and spoofing

Traditional GPS systems are highly vulnerable to spoofing. A low-cost software-defined radio (SDR) can be used to spoof GPS signals. Current spoofing techniques can challenge complex receiver defenses, making research and development in spoofing prevention urgent—especially for restoring accurate navigation after incidents. It is also important for receiver manufacturers to implement built-in spoofing defenses.

MMW radar attacks

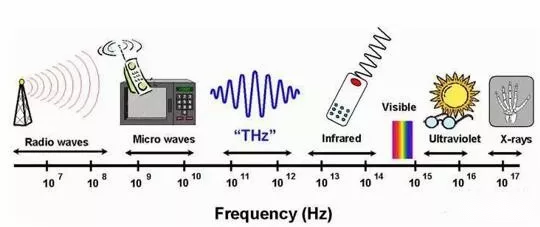

Millimeter-wave radar has an advantage in resisting adverse weather and can operate continuously, making it an essential core sensor for advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS). Automotive MMW radar typically operates around 24 GHz and 77 GHz, with the latter enabling more compact systems. At the 2016 DEF CON conference, researchers used a micro ultrasonic transmitter to successfully jam and spoof a commercially deployed MMW radar, causing temporary "blindness" and malfunctions that pose serious safety risks.

LiDAR sensor attacks

Researchers from the RobustNet group at the University of Michigan and a team at the University of California, Irvine found that LiDAR perception systems can be spoofed. Attackers can send light signals to confuse the pulses received by the sensor, creating phantom obstacles. This can cause sudden braking and collisions.

Ultrasonic sensor attacks

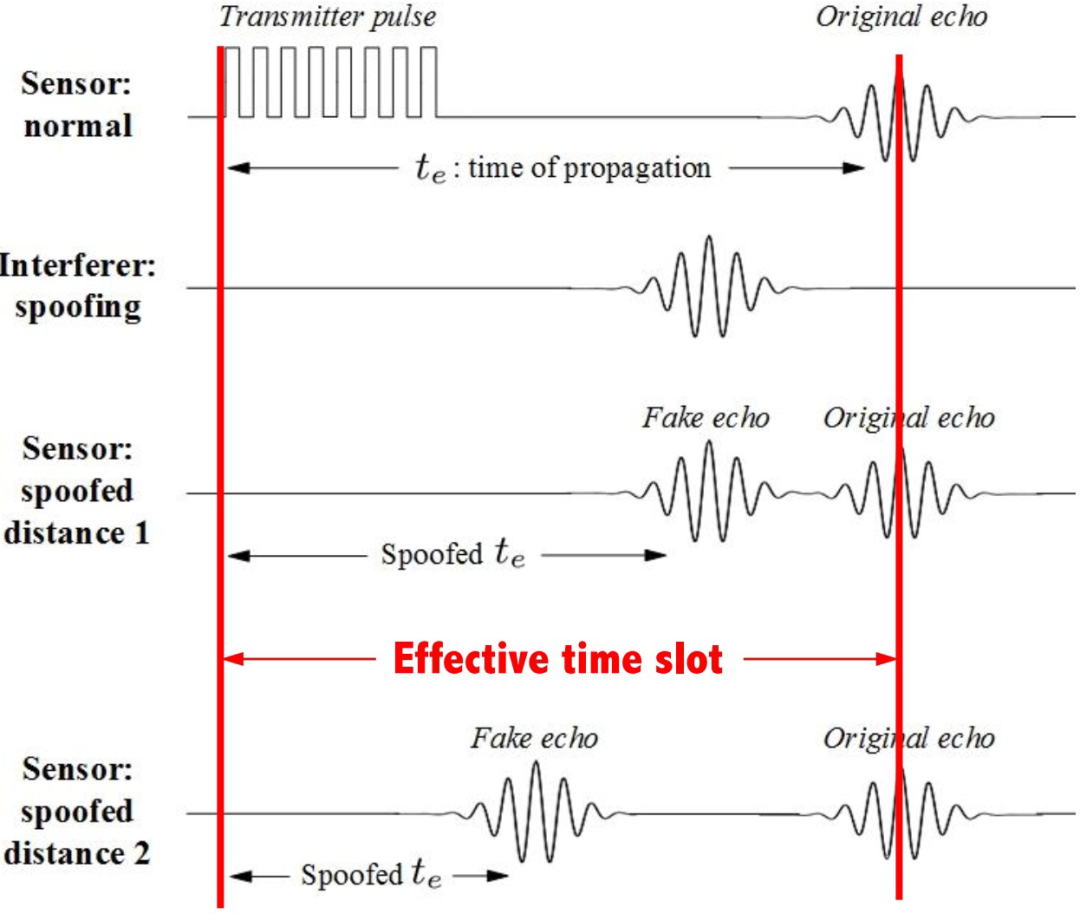

The diagram shows a spoofing attack on an ultrasonic sensor. In 2016, researchers demonstrated a spoofing attack against a vehicle's ultrasonic sensors by sending crafted fake echoes before the real echo arrived. By tuning the timing of the fake echoes, attackers can manipulate the measured angle and cause the sensor to detect non-existent objects, potentially leading to collisions.

Camera sensor attacks

Camera sensor attacks generally fall into two categories: 1) attacks via web services connected to cameras; and 2) attacks via real-time streaming protocols such as RTSP. In one case, a camera manufacturer shipped 175,000 devices with a buffer overflow vulnerability that could allow remote attackers to execute arbitrary code and take full control, leading to unpredictable consequences.

Vehicle Access Attacks

Key cloning

A 2020 study by researchers at KU Leuven and the University of Birmingham showed that mechanical key encryption schemes used by some manufacturers can be vulnerable. Attackers can exploit flaws to eavesdrop on a single signal from the original remote and clone the car key, potentially stealing a vehicle within minutes. Some manufacturers have since introduced Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) to store keys in hardware so that stolen data cannot be decrypted, protecting sensitive information at its source.

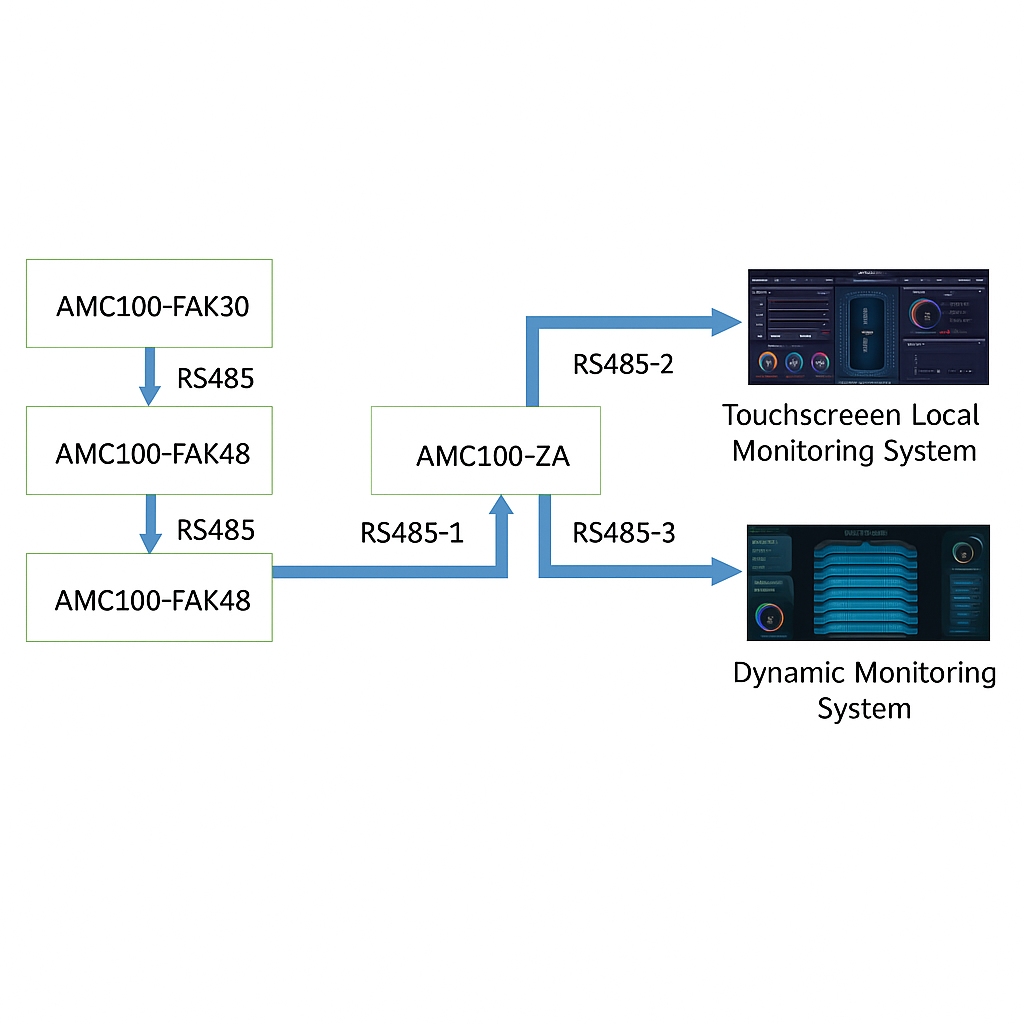

Telematics and remote service attacks

The SAE J1939 protocol, developed alongside the CAN bus, remains widely used in the networking of commercial vehicles and heavy equipment. Researchers at the University of Michigan found that an attacker with network access could use the SAE J1939 protocol to control safety-critical systems in medium and heavy vehicles. To mitigate such risks, software developers must build security mechanisms into vehicle software from the design stage to guard against these attacks.

Conclusion

As the intersection of industrial digitalization and digital industry, the essence of connected vehicles is the "software-defined car." This shift means security concerns extend beyond traditional physical safety into complex digital security. Connected vehicles require more comprehensive protection to safeguard enterprises, vehicles, users' information, property, and personal safety.