48V low-voltage system design

01

History of low-voltage systems

The first mass-produced cars used a 6 V architecture starting in 1918. By the 1950s, large-displacement engines in the U.S. increased electrical demand beyond what 6 V systems could supply, so automakers began connecting two 6 V batteries in series to form a 12 V low-voltage system.

By the late 1960s almost all cars used a 12 V electrical system. Components and subsystems such as power windows, interior lighting, cigarette lighters, brake lights, ignition, and batteries were standardized around a 12 V nominal voltage. That situation has changed little in nearly 60 years.

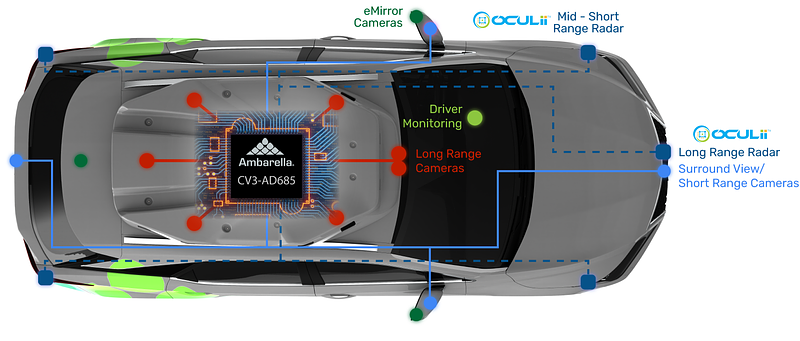

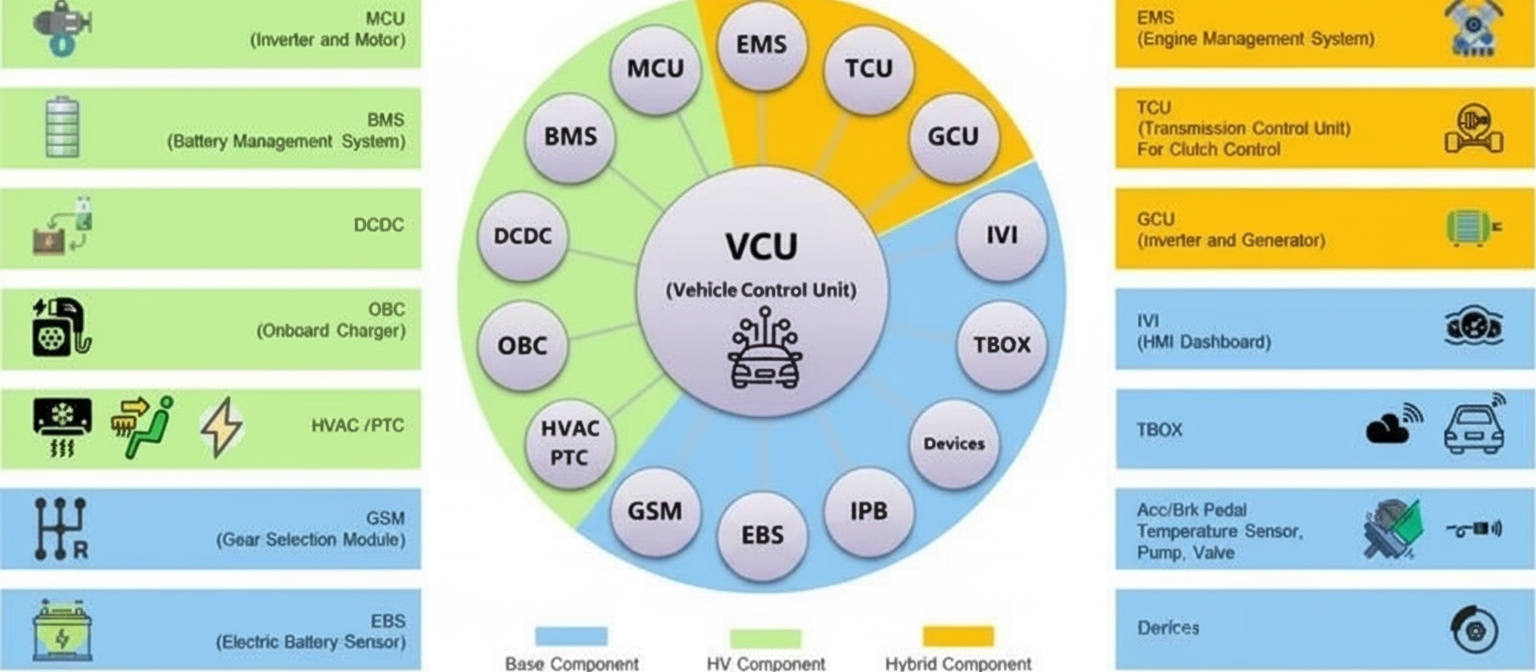

In traditional 12 V systems, each control unit for functions like air conditioning, driver assistance, and infotainment often required separate wiring. As vehicles integrated more electrical components, wiring became increasingly complex and inefficient, which is less compatible with electrification and vehicle intelligence trends.

Advanced electric vehicles with strong driver-assist capabilities — for example, perception and compute systems, actuation components for assisted driving, steer-by-wire and brake-by-wire, and high-speed transmission of 4G/5G information — impose higher demands on power delivery.

In 2011 Audi, BMW, Daimler, Porsche, and Volkswagen jointly promoted 48 V systems to meet growing onboard electrical loads and stricter emissions regulations.

Proponents of 48 V systems, led by several German automakers, integrated a 48 V domain alongside existing 12 V systems using DC/DC converters. They also proposed DC/DC devices that would convert high-voltage traction battery power into both 12 V and 48 V rails to drive different components. Although these approaches were incremental to the 12 V architecture, adopting a higher-voltage electrical system has been a focus for automakers to address limitations of the 12 V architecture. The Cybertruck is Tesla's first production vehicle to use a 48 V electrical system across the vehicle.

02 Advantages of 48V systems

As onboard device power increases, keeping voltage low requires higher currents, which raises thermal losses and forces thicker cable cross-sections, increasing vehicle weight and energy consumption and reducing range. Raising the voltage to 48 V enables delivery of higher power while reducing line losses and heating, offering clear advantages over 12 V systems.

First, a 48 V system can support higher electrical loads and enable more power-hungry functions. At the same current, a 48 V system delivers more power than a 12 V system; at the same output power, a 48 V system requires lower current and therefore reduces power loss.

Tesla removed the 12 V battery in the Cybertruck and retained only a 48 V battery to raise operating voltage and lower current. Tesla also designed ECU power modules that can provide selectable 12 V or 5 V outputs for legacy electronics.

Second, compared with traditional systems, 48 V systems are more efficient, reducing power loss and improving durability and safety. Increasing voltage by four times while reducing current to a quarter decreases energy loss and cable heating, which can extend harness life and improve safety while enabling faster response from electrical components.

Third, lower current permits lighter cables, reducing wiring size and weight, saving cost and creating more space for passengers or batteries.

Because current relates to copper use, reducing current can save substantial copper. Tesla reported the Cybertruck's 48 V architecture reduced wiring by 77% and copper demand by 50%, lowering overall weight and improving efficiency. Tesla estimated annual savings on wiring-related cost on the order of several billion dollars.

Fourth, 48 V systems can simplify vehicle architecture. For example, the Cybertruck uses high-speed data buses such as Ethernet to replace or reduce CAN bus point-to-point wiring, enabling daisy-chained connections for many components in legacy systems.

03 Challenges facing 48V architectures

Although 48 V systems have many benefits, they introduce new challenges.

First, complexity and safety are key concerns. Faults or security vulnerabilities in the higher-voltage domain can have serious consequences and must be carefully managed.

Second, legacy OEMs' hesitation to adopt a new system slows deployment. Tesla's 48 V low-voltage system may not be adopted immediately by other automakers; the industry may require a long transition period before 48 V architectures become widespread.

Third, the supplier ecosystem will be reshaped. A 48 V domain requires development and production of components that operate at the higher voltage, which will alter wiring, connectors, and electrical engineering practices across the automotive supply chain.

If an automaker decides to adopt 48 V architecture across its lineup, it must obtain compatible components for all vehicles. Suppliers have little incentive to produce 48 V parts without sufficient demand. Low volumes would likely keep per-unit costs for 48 V parts well above those for mature 12 V products.

Therefore, traditional automakers that rely on third-party suppliers often progress slowly in rolling out 48 V systems. Many will transition gradually across model lines.

Tesla's Cybertruck provides a reference point for 48 V system design. As other automakers recognize the benefits of 48 V systems, they will need to invest in necessary technologies and infrastructure to convert systems, or risk losing market share and profitability.

04 Why share a 48V architecture

Tesla has two structural advantages when transitioning to 48 V that many traditional automakers do not share.

First, Tesla uses an unusually vertically integrated manufacturing approach — Tesla designs nearly all vehicle systems internally, even if some components are sourced externally.

Second, Tesla had few legacy design constraints when deciding to change electrical architecture. Tesla has internal teams focused on developing components tailored for 48 V architectures, such as lighting, winches, and air compressors. Vertical integration and in-house manufacturing give Tesla flexibility to design and produce highly integrated components and accelerate transition to 48 V.

However, adopting 48 V requires redesigning vehicle electrical systems, providing compatible charging infrastructure, ensuring safety during charging, driving, and parking, and developing standards to ensure compatibility and interoperability with other vehicles.

Tesla's decision to share technical documentation for its 48 V architecture appears strategic rather than purely altruistic. By sharing its approach, Tesla reduces barriers for others to adopt 48 V systems and helps expand the overall market, which can yield strategic advantages similar to prior cases of shared EV patents and charging interfaces.

Tesla recognizes the transition will be difficult for traditional automakers. Even large companies with ample resources cannot build a 48 V component supply chain overnight; the change requires substantial nonrecurring engineering work.

Publishing technical details signals to other manufacturers: "We will show how we implemented this. It is complex and will take years to reproduce, but you can follow our approach." Opening the architecture can encourage broader industry adoption, which benefits Tesla by helping shape standards, reducing supply costs over time through scale and competition, and growing the talent pool of engineers experienced with 48 V systems.

For engineers and vehicle system designers, accelerating the supplier ecosystem's move to 48 V offers significant benefits. Increasing the number of components designed for 48 V reduces unit costs, improves reliability through engineering iteration, and builds shared knowledge across the industry.

Adopting 48 V systems can create new business opportunities and strengthen an automaker's position as a technical leader. The Cybertruck demonstrates practical advantages of a 48 V architecture, and Tesla's shared documentation is likely to accelerate industry movement toward 48 V low-voltage systems.