As vehicle intelligence and connectivity penetrate the market, the share of automotive electronics and electrical components in vehicles has steadily increased. Advanced driver assistance systems and in-vehicle multimedia systems have become important factors in consumer purchase decisions. The growing complexity of these systems increases demand for sensors and electronic control units (ECUs), for example cameras and millimeter-wave radar for automated driving, passenger entertainment displays, HUD heads-up displays, engine control modules (ECM), battery management systems (BMS) for new energy vehicles, and AVM modules for 360-degree surround-view image fusion. A modern luxury vehicle can contain 70 to 100 ECUs. Traditional distributed electrical/electronic architectures (EEA) can no longer meet development needs for multiple reasons:

Limitations of Distributed Architectures

1. Inefficient use of dispersed compute resources.

2. Wiring harness cost and weight disadvantages.

3. Inability to support high-bandwidth in-vehicle communications.

4. Difficulties with upgrades and maintenance.

Centralized electronic/electrical architectures have emerged to address these limitations and will likely evolve toward central computing platforms.

1. Dispersed Compute Resources

In a distributed architecture, vehicles carry dozens of controllers. To ensure stability and safety, each controller typically has hardware compute headroom relative to the tasks it runs. This creates a vehicle-level situation where controller capabilities operate in isolation and cannot coordinate efficiently. In a centralized architecture, compute resources can be shared across functions: for instance, compute used for driver assistance while driving can be reallocated to in-vehicle gaming when parked.

2. Wiring Harness Cost and Weight

A large number of ECUs implies complex and lengthy wiring harnesses. According to industry data, an advanced vehicle may use about 2 km of wiring harness, weighing 20–30 kg. Cable materials alone account for roughly 75% of harness weight. Introducing domain controllers and centralized architectures can greatly reduce harness length and weight.

3. High-Bandwidth In-Vehicle Communication

In the distributed ECU era, control relied on MCU chips and low-speed buses such as CAN, LIN, and FlexRay. As ECU counts grew, bus load reached near capacity, causing dropped frames and bus congestion with potential safety implications. Domain controllers use high-performance heterogeneous chips as domain masters and employ high-speed networking such as Ethernet for inter-domain communication. 100 Mbps and 1 Gbps automotive Ethernet have been applied in multiple new models. Although per-node cost for automotive Ethernet initially exceeds CAN or LIN and is comparable to FlexRay, data rate limitations will make Ethernet the unavoidable successor to traditional buses.

4. System Integration and OTA Maintenance

ECU development is often performed by multiple Tier1 suppliers while OEMs integrate systems. This places high demands on OEM integration and supplier management. The scattered layout of distributed ECUs also hinders over-the-air (OTA) updates, complicating software maintenance. OTA updates have become common across vehicle makers, with update frequency increasing rapidly year over year.

From Distributed ECUs to Domain Controllers

Traditional vehicle E/E architectures connected ECUs via CAN and LIN buses, coordinating sensors, power and communications chips, and actuators to control vehicle states and functions. Historically, each control function had a dedicated ECU, so adding a feature meant adding an ECU. Under rising electrification and intelligence requirements, the architecture evolved into domain-centralized designs, creating the concepts of "domain" and "domain controller". Domain controllers were proposed by Tier1 suppliers such as Bosch, Continental, and Delphi, aggregating multiple ECUs into domains managed by higher-performance multi-core CPU/GPU chips and using Ethernet to concentrate compute and reduce distributed limitations.

Advantages of Domain-Centralized Architecture

1) Cost savings and reduced assembly complexity. A domain architecture separates sensing from processing, reduces one-to-one pairing of sensors and ECUs, and reduces the number of ECUs and wiring harnesses, lowering hardware and installation costs and improving packaging.

2) Improved communication efficiency and software/hardware decoupling, facilitating OTA upgrades. Unified management of software frameworks and communications reduces redundancy and simplifies maintenance and OTA deployment.

3) Concentrated compute and reduced redundancy. Aggregating previously distributed ECUs into domain controllers enables unified data processing, lowering compute redundancy and better meeting high compute requirements of advanced automated driving.

Domain Partitioning

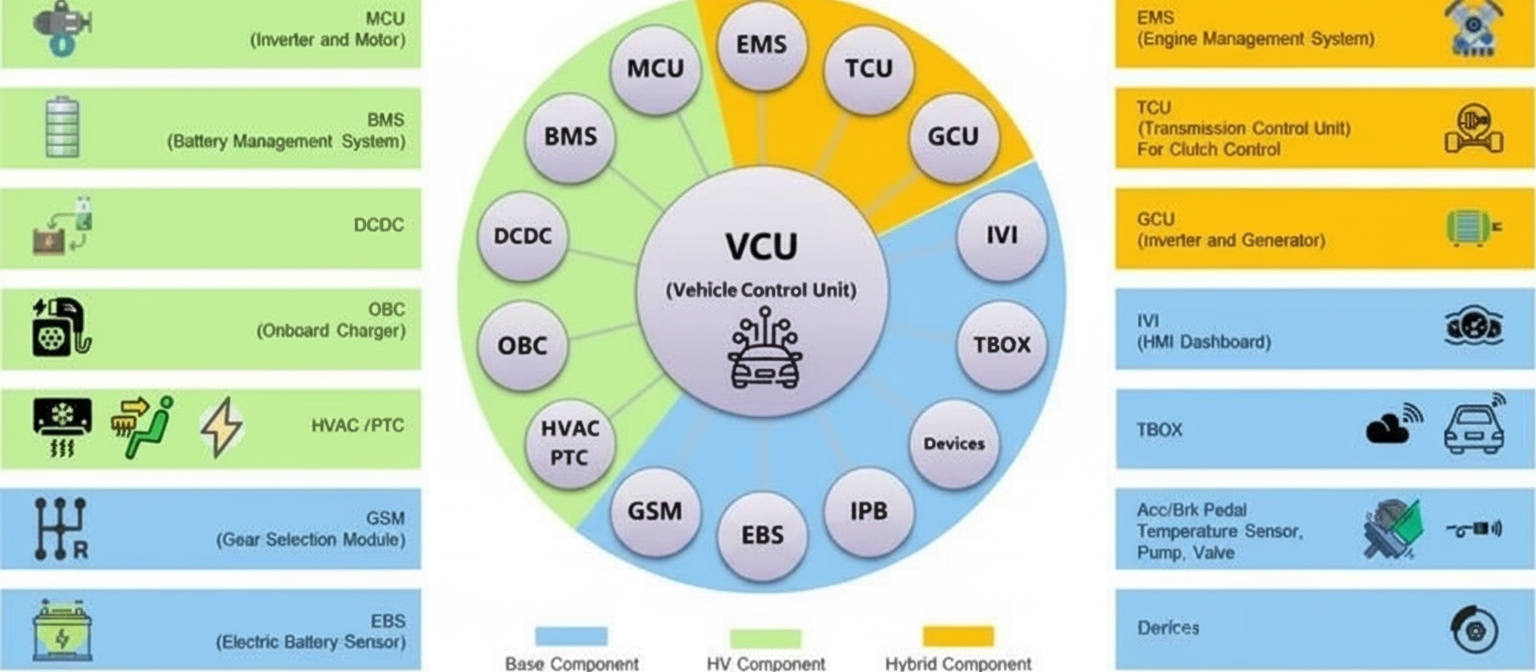

Based on functional concentration, Tier1 suppliers typically divide vehicle electronic control into five domains: powertrain (safety), chassis (vehicle dynamics), cockpit (infotainment), automated driving, and body.

Powertrain Domain

The powertrain domain optimizes and controls propulsion while handling electrical fault diagnostics, intelligent energy saving, and bus communication. Powertrain domain controllers manage torque distribution across internal combustion engines, electric motors/generators, batteries, and transmissions, support CO2 reduction strategies through predictive control, and serve as communication gateways.

Chassis Domain

The chassis domain integrates braking, steering, suspension, and other longitudinal/lateral/vertical vehicle control functions for unified control. It can include control of air springs, damper control, rear-wheel steering, electronic stabilizers, and steering column position control. Implementing these functions requires integration of chassis drive, braking, and steering algorithms.

Cockpit Domain

The cockpit domain integrates HUD, instrument cluster, infotainment, and implements a "one-chip multi-screen" approach. Typical components include full LCD clusters, central infotainment displays, HUD, streaming rearview mirrors, and more. The cockpit domain controller uses Ethernet/MOST/CAN to fuse HUD, dashboard, navigation, and other components, and it can further integrate ADAS and V2X systems to optimize driving assistance, connectivity, and infotainment. Cockpit domains enable independent perception and upgraded interaction modes, moving from physical buttons to touch, voice, and gesture interfaces.

Automated Driving Domain

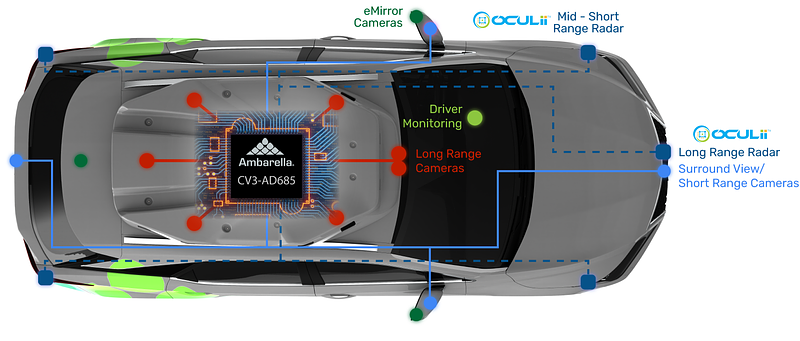

The automated driving domain provides multi-sensor fusion, localization, path planning, decision control, image recognition, high-speed communications, and data processing. It typically connects multiple cameras, millimeter-wave radars, lidar, and other sensors. Algorithms perform perception, multi-sensor fusion, and decision planning, and output control commands to actuators for longitudinal and lateral control. Because it handles large amounts of data, the automated driving domain requires high compute capability and typically uses high-performance SoCs with heterogeneous accelerators.

Body Domain

The body domain integrates traditional body control module (BCM) functions, HVAC flaps, tire pressure monitoring, passive entry passive start (PEPS), and gateway functions. Body domain controllers centralize body electronics control and unify analysis and processing of collected information. They require BCM development experience, hardware integration capability, software architecture, and chip supply assurance, and may integrate gateway and lower-level ADAS functions, with early convergence toward the cockpit domain.

Key Domains Today

The cockpit and automated driving domains currently carry the vehicle personalization and intelligent experience, and are the main competitive focus for OEMs. These domains require substantial AI compute and sophisticated OS-level and algorithm support. Other domains involve more safety-critical mechanical components and therefore demand higher functional safety assurance but lower compute intensity.

From the supplier perspective, cockpit and autonomous driving domains have relatively complete supply systems, while other domains are further integration of traditional systems involving many suppliers and potential conflicts. As electronic modules achieve economies of scale, their unit value may decline. Chassis, powertrain, and body domains may further integrate into region-based domain assemblies as vehicles move toward more centralized architectures.

Domain Controller Architecture

From a structural perspective, a domain controller comprises hardware (main SoC and components) and software (low-level platform, middleware, and application algorithms). Functionality arises from the integration of main SoC chips, operating systems, middleware, and application software.

Hardware

Hardware includes the main SoC, printed circuit board, passive components (resistors, capacitors), RF components, brackets, thermal solutions, sealing metal enclosures, and other parts. The main SoC is the core. For cockpit and automated driving domains that require high compute, SoCs combine MCUs for vehicle control with CPUs, GPUs, audio DSPs, NPUs for deep learning acceleration, ISP image processors, ASICs, and FPGAs as needed to support hardware acceleration. Chassis, body, and powertrain domains often continue to use traditional MCUs due to lower compute requirements and cost considerations. The trend moves toward higher-performance single SoCs.

Software

Software includes low-level operating systems, middleware and development frameworks, and upper-layer application software. Low-level OS options include automotive-grade OS, custom OS, virtual machines, and kernels. Middleware and frameworks such as AUTOSAR and SOA sit between OS and applications, abstracting processor and OS details and providing core services for vehicle networks and power management. Upper-layer applications include cockpit HMI, ADAS/AD algorithms, connectivity, and cloud integration. Low-level operating systems are a focus area for many Tier1s, while middleware and application layers are where OEMs differentiate functionality.

Upstream Suppliers

Key upstream hardware suppliers for main SoCs include global players such as Mobileye, Qualcomm, NVIDIA and Chinese vendors such as Horizon, Black Sesame, and Huawei. MCU suppliers include NXP, Infineon, Renesas and other established MCU vendors. On the software side, low-level OS suppliers in the Chinese market include several domestic providers, while middleware suppliers include EB, Vector, TATA, Mentor, ETAS, KPIT, and newer domestic entrants such as TTTech, Unisound, Neusoft Reach, ThunderSoft, and others.

Low-compute cockpit SoC supply is fragmented. Besides traditional automotive SoC vendors like NXP, Renesas, and TI, consumer-electronics chip vendors such as Qualcomm, Intel, NVIDIA, Huawei, AMD, and MediaTek are entering the space. Chinese chip companies such as Jiefa, CHIPS, Rockchip, Horizon, and others are also pursuing automotive chips, reshaping the market landscape.

Midstream Domain Controller Integrators

International Tier1 integrators include Bosch, Visteon, Delphi, Continental, and ZF. Chinese Tier1 suppliers include Desay SV, KBO, Huayang Group, Joyson Electronics, and Jingwei Hirain.

Participants in cockpit domain controller development include OEMs, domain controller integrators, and software developers. OEMs and software firms often focus on software and algorithms but lack chip adaptation and mass-production capabilities. Traditional Tier1s remain key due to deep chip partnerships and volume manufacturing expertise. Several Chinese Tier1s have developed and mass-produced cockpit domain controllers based on high-profile chip platforms and secured OEM projects.

International Tier1s have a head start in cockpit domain offerings. For example, Visteon began development in 2012 and released the first production cockpit domain controller in 2018, winning OEM orders. Bosch and partners have likewise secured multiple OEM projects with 8155-based cockpit controllers and have achieved single-chip dual-system multi-terminal production.

Automated Driving Domain Suppliers

Main participants in automated driving domain controller development fall into several categories:

1) A few leading OEMs pursue in-house automated driving domain controller development. Some new-car OEMs and leading independent automakers develop central compute and domain modules internally, sometimes outsourcing manufacturing to contract manufacturers. Full in-house development remains challenging for most OEMs, so many will continue to rely on Tier1s and algorithm suppliers in the medium term.

2) International Tier1s hold customer and supply-chain advantages in automated driving domain controllers, including suppliers such as Visteon, Bosch, Continental, ZF, and Magna. Representative products include Visteon DriveCore, Bosch DASy, Continental ADCU, ZF ProAI, Veoneer Zeus, and Magna MAX4. These platforms support various high-compute chip options and can reach high functional safety levels.

3) Chinese Tier1s seek differentiation by integrating high-compute chips. Examples include Desay SV, Jingwei, Joyson, Huawei MDC, and Nobo Technology. Desay SV has developed multiple generations of automated driving controllers (IPU01 through IPU04), collaborating with OEMs and NVIDIA, achieving production-scale deliveries with Orin-based platforms delivering up to hundreds of TOPS of compute.

4) Software platform vendors and startups with strong algorithm capabilities are entering domain controller hardware to capture integrated solutions. High-quality autonomous driving software stacks are in demand and serve as a driver for these companies to move into hardware design and manufacturing to interface directly with OEMs.

OEM and Supplier Collaboration Models

Under software-defined vehicle trends, relationships between OEMs and suppliers are shifting. Whereas OEMs previously issued fixed requirements to Tier1s that developed controllers, the rise of vehicle intelligence has led many OEMs to build in-house software and even hardware teams. Collaboration models now include:

1) Turnkey: Suppliers deliver hardware, OS, middleware, and applications; the OEM integrates the system. This suits autonomous driving solution providers and cockpit software platform vendors and often involves ODM/OEM contract manufacturers for production.

2) Application in-house: Suppliers provide hardware, OS, and middleware; OEMs develop application-layer software. This white-box or gray-box approach enables OEM control of application logic while leveraging Tier1 manufacturing and chip vendor stacks.

3) Middleware up in-house: Suppliers provide hardware and OS; OEMs develop middleware and applications. Suppliers focus on foundational software platforms while supporting OEM autonomy above the middleware layer.

4) Hardware contract manufacturing: Suppliers perform hardware manufacturing only. This model was pioneered by some OEMs and adopted by new entrants who design in-house and outsource production.

5) Tier0.5: OEMs create or partner with Tier1s to form vertically integrated suppliers to pursue full-stack in-house capabilities, often via subsidiaries or joint ventures.

Market Outlook in the Chinese Market

Passenger car volumes in China are expected to stabilize, with forecasts of approximately 23.23 million vehicles in 2025 and 23.93 million in 2030. New energy vehicle (NEV) penetration in the Chinese market is projected to grow rapidly: NEV sales in China reached significant numbers in recent years and are expected to be around 15 million in 2025 and 21 million in 2030 under median assumptions used for subsequent calculations.

Cockpit Domain Market Forecast

Cockpit domain costs are driven mainly by chips. Using current market prices for widely used chips as a reference and accounting for hardware and production costs, an assembled cockpit domain controller price is estimated around CNY 2,000–2,500. With chip price declines expected and supply shortages easing, assembled prices could drop to CNY 1,800–2,200 by 2025 and lower by 2030. Given relatively low development difficulty and high consumer-visible value, NEV manufacturers are aggressively adopting cockpit domains. Cockpit domain controllers are expected to reach near-full penetration in NEVs and expand into some ICE vehicles, making the cockpit domain the fastest-growing domain. The cockpit domain market in China is projected to reach CNY 34.9 billion by 2025 and exceed CNY 40 billion by 2030.

Automated Driving Domain Market Forecast

Automated driving domain controllers can be segmented by function level: L2, L3, and L4.

L2 domain controllers are expected to be used in economy models priced roughly CNY 100k–200k, with current average prices around CNY 2,300–2,500. With chip cost reductions and scale, the 2025 average is expected below CNY 2,000. L2 hardware penetration will grow from around 20% in 2021, potentially reaching 50% by 2025, and later declining as OEMs re-evaluate low-level autonomy strategies. Domain controller penetration within L2 hardware is expected to rise to 100% by 2030.

L3 and L4 domain controllers target higher-end vehicles priced above approximately CNY 300k and typically use high-compute chips such as NVIDIA Orin. Orin pricing and the need for multiple chips plus sensors, lidar, and software development result in estimated assembled domain controller prices near CNY 15,000 initially, with declines expected as volume scales.

Policy support and continued R&D are expected to drive L3/L4 penetration. Several OEMs and integrators are targeting L3+ deployments before 2025. Regulatory pilots enabling L3 vehicles to operate on public roads also support growth. High-compute SoC advancements, such as upcoming chips with substantially higher TOPS, will further enable higher-level autonomy. L3 domain controller penetration is projected at 10%–20% by 2025 and above 40% by 2030. L4 penetration is estimated at 1%–5% by 2025 and above 20% by 2030.