Electronic control in vehicles

Electronic control devices were first applied to automobiles in 1968. Volkswagen’s rear-wheel-drive 1600 LE/TLE was fitted with Bosch’s D-Jetronic electronic fuel injection system. Three years later, Nissan introduced the Bosch-produced L-Jetronic electronic fuel injection system on the Bluebird U 1800 SSS-E. To meet stricter emissions regulations, systems that precisely control the air-fuel ratio gradually replaced carburetors and became the mainstream fuel supply method.

After more than 50 years of development, electronic control systems in vehicles are entering a new phase. Until now, a vehicle’s value was mainly determined by its basic functions: driving, steering, and stopping. Driving includes increasing engine output, reducing noise, and improving ride comfort; steering covers handling stability; stopping covers braking improvements. Much of this value has historically been provided by mechanical hardware.

However, the ongoing transformation in the automotive industry is shifting how value is created — from traditional hardware toward software. This not only implies faster growth of electronic control in vehicles than before, but also a potential fundamental impact on the business models of automakers, parts suppliers, and related industries.

CASE as the starting point

When discussing software-defined vehicles, it is important to note the major industry trend often summarized as CASE: Connected, Autonomous, Shared & Services, and Electric. CASE represents connectivity, autonomy, shared mobility and services, and electrification. This concept has become a key driver of industry change.

Why is CASE so significant? Because it is upending traditional automotive values. First, connectivity challenges the notion of the car as an isolated private space. Second, autonomy challenges the value associated with driving enjoyment by eliminating the driving act itself. Third, shared mobility undermines the value of vehicle ownership; like Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS), users can call vehicles on demand rather than owning them. Finally, electrification targets the internal combustion engine, which has been a core symbol of a vehicle’s character — its power, vibration, and sound have historically defined brand identities.

CASE can be seen as a rejection of many values automakers have long pursued. In other words, it is a value revolution that risks devaluing accumulated expertise and technologies in traditional firms. So why has such a sweeping wave of transformation emerged?

China’s automotive strategy

China has articulated a strategic goal to become a leading automotive power by 2035 through technological and brand leadership. Given the difficulty of catching up with advanced nations in the traditional internal-combustion vehicle sector, China has focused on early and broad adoption of electric vehicles and smart connected vehicles equipped with autonomous driving technologies, using its accumulated capabilities to expand globally.

By 2022, sales of battery-electric vehicles in China rose 81.6% year-on-year to 5.365 million units, accounting for about 20% of new car sales. Of the global electric vehicle sales of 7.8 million units, nearly 70% were in China. In addition, Chinese production of traction batteries accounts for over 60% of the global market. By driving the CASE transformation, China’s automotive industry is steadily increasing its influence domestically and internationally.

BYD, China’s largest new-energy vehicle manufacturer, has begun expanding into global markets.

IT giants targeting the automotive market

Another key driver behind CASE is the major IT companies. Apart from Meta (formerly Facebook), companies such as Google, Amazon, and Apple see the automotive sector as a new business market and are monitoring opportunities to enter.

For example, Google began developing autonomous driving technology in 2010 and is commercializing driverless taxi services in Phoenix, Arizona, with plans to expand to other cities. Amazon has invested in Rivian and acquired Zoox, positioning itself to move from logistics automation into automotive services. Apple’s reported moves into the autonomous electric vehicle space focus on user interface strengths that could differentiate its offering. These IT firms emphasize software and network-based business models rather than traditional vehicle hardware, prompting incumbent automakers to accelerate changes to compete.

The emerging outline of the software-defined vehicle

As competition intensifies to create value via software and networks in next-generation vehicles, governments, regions, and companies are advancing initiatives. The result is the concept of the software-defined vehicle (SDV). While there is no single definitive definition yet, its contours are becoming clearer.

Historically, a vehicle’s value came largely from hardware performance and engine output. Metrics such as steering responsiveness, chassis rigidity, ride comfort, and throttle response defined a car’s quality. These attributes remain important, but their manifestation will change significantly in future vehicles.

Personalization that breaks hardware boundaries

In traditional cars, users have limited ability to change characteristics such as steering behavior, ride comfort, or throttle feel — at best switching between “normal” and “sport” modes. New electric vehicles already offer increased configurability, for example allowing users to set the level of regenerative braking when releasing the accelerator. Future cars will be able to adjust suspension stiffness and brake response via software based on driver preferences or have onboard AI learn and automatically optimize settings for a better driving experience.

When autonomous driving advances, the speed and style of steering inputs during autonomous operation and overall vehicle behavior may be adjusted according to occupant preferences. Vehicles may also support downloadable apps from an application store, similar to smartphones.

Users could download navigation packages and install entertainment apps, instrument cluster themes, and in-car games. Software-based feature selection and expansion will break traditional constraints and support extreme personalization. As a result, a vehicle’s functionality and performance can improve after purchase through software upgrades, potentially helping to preserve residual value over time.

Volkswagen’s software subsidiary CARIAD has launched an in-vehicle app store to distribute applications for its platform.

Post-sale value retention

Vehicle use patterns will change as well. More users will spend time in the car listening to music, watching video, working, or communicating remotely. Vehicles will need entertainment systems, conferencing tools, and in-vehicle social applications, and these services will be provided as software. The professional term SDV refers to vehicles whose value is largely defined by software.

Separating software and hardware

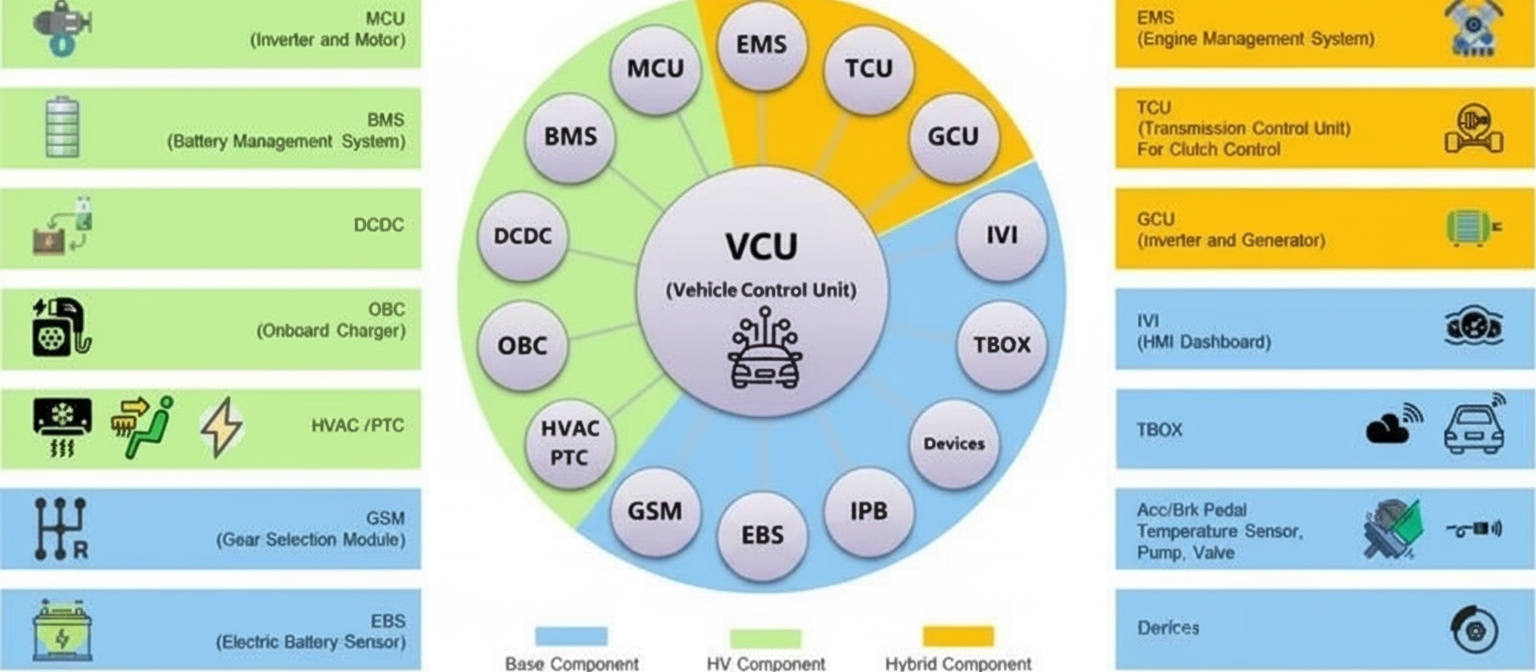

Future vehicles require flexibility to support continuous software upgrades, additions, or removals. Existing electronic control units (ECUs) used for vehicle control are not well suited to this need because they tightly integrate embedded software with dedicated hardware. For example, an engine control ECU and its engine control software are typically inseparable. This integration makes it difficult to apply flexible software updates. Consumer-grade cars often contain 30–40 ECUs, and equipping every simple ECU with update and reprogramming capabilities is impractical.

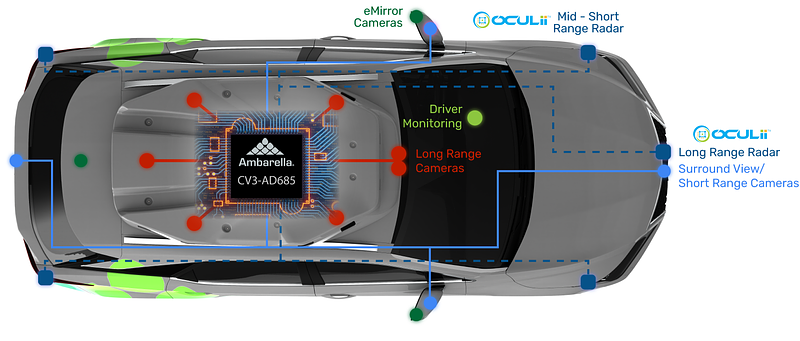

SDV architectures aim to separate ECUs and software. Instead of numerous small ECUs distributed across the body, functions are consolidated into a few high-performance ECUs running multiple software instances. This is the centralized or zonal ECU approach. For example, ECUs may be categorized into units for autonomous driving and driver assistance, units for powertrain control, and units for instrument clusters and infotainment.

Upgrading the electrical/electronic architecture

To support the SDV model and post-sale software evolution, automakers plan to adopt integrated ECUs for hardware-software separation. Traditionally, ECUs for the engine, brakes, and transmission communicate via CAN bus to enable coordinated control. This network of ECUs constitutes the vehicle’s electrical/electronic (E/E) architecture.

Future E/E architectures are expected to consolidate functionality into high-performance ECUs dedicated to domains such as powertrain, ADAS/autonomous driving, and infotainment, running multiple software workloads. The hypervisor is a key enabling technology for this consolidation.

The role of the hypervisor

A hypervisor is a virtualization monitor that enables multiple virtual ECUs (virtual machines) to run concurrently on a single system-on-chip (SoC) and to host specific applications in separate virtual machines. It allows mixed usage of different operating systems and isolates faults or malware so that a failure in one virtual machine does not affect others.

Running multiple applications on a single chip is common in smartphones and laptops, but automotive software has much higher safety and reliability requirements. Virtualization helps isolate applications to meet those requirements.

SoCs designed for virtualization

SoCs designed to support hypervisor-based virtual machines have appeared on the market. For example, in January 2023 Qualcomm announced the Snapdragon Ride Flex SoC, which integrates IVI, ADAS, and instrument cluster functions on a single chip. The SoC supports running real-time-critical software such as ADAS and instrument clusters and non-real-time IVI workloads in separate virtual machines on top of a hypervisor.

Ultimately, the main distinction of SDVs is the decoupling of software and hardware through virtualization and virtual machines, enabling vehicles to be freely upgraded and extended via software. Automakers are expected to accelerate adoption of integrated ECUs from the mid-2020s, potentially disrupting traditional automotive business models.

AWS expanding into automotive

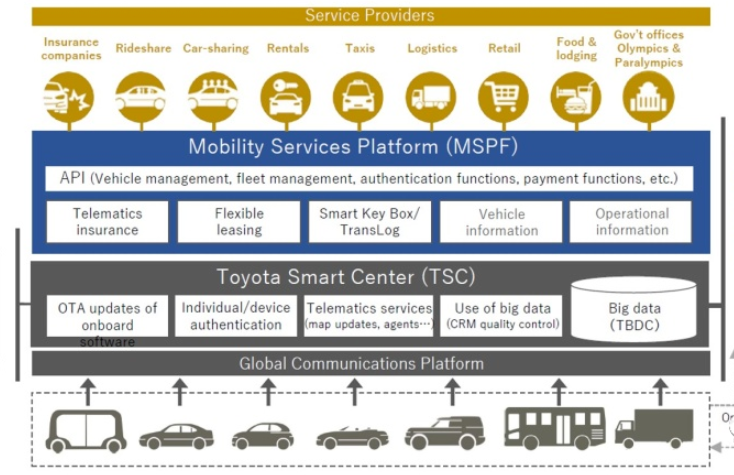

AWS has proposed several SDV capabilities and use cases that illustrate how cloud services might support modern vehicle development and operations. Cloud computing is increasingly involved at every stage from R&D to in-service operations. Large-scale simulation that used to run on in-house mainframes is now performed in the cloud. For ADAS and autonomous driving development, cloud platforms are routinely used to process and label large volumes of sensor data for machine learning.

For rapid deployment of connected services and OTA software updates worldwide, cloud platforms are indispensable. AWS is rapidly expanding its footprint in automotive, though its overall cloud market share is about 30% and it has historically trailed competitors in automotive-specific services.

Toyota and BMW adopting AWS

AWS has targeted automotive as a priority vertical. In 2020 Toyota migrated some of its connected services to AWS, benefiting from serverless features that scale with usage. Toyota reported server cost reductions of up to 70–80% after adopting AWS. Toyota’s R&D subsidiary TRI-AD (now Woven Core) also uses AWS for deep learning model development, accelerating training times significantly by leveraging cloud scale.

AWS is also collaborating with BMW to provide the cloud data platform for BMW’s Neue Klasse, a next-generation strategic EV launching in 2025. BMW expects the new platform to handle about three times the current data volume. Neue Klasse is positioned as BMW’s first software-defined vehicle, and the new cloud data platform is expected to enable more personalized services and iterative improvement based on user feedback.

AWS SDV use cases

AWS has outlined several SDV scenarios. First, for hard-to-diagnose incidents such as phantom braking, AWS envisions modifying data collection strategies from the cloud after a vehicle has left the factory to capture additional telemetry. Second, vehicle dynamics parameters like powertrain output and suspension settings could be altered remotely for specific use cases, such as boosting output on a racetrack. Third, parked-vehicle monitoring could detect intentional damage via surround cameras, trigger recording, and play a recorded warning message to deter vandalism.

OEM software strategies

The following summarizes software strategies being pursued by major automakers.

Volkswagen: increasing revenue through software

In July 2021 Volkswagen announced its mid-term strategy “NEW AUTO: MOBILITY FOR GENERATION TO COME” to address future mobility market changes. Volkswagen projected that by 2030 the global automotive market could exceed €5 trillion, with software-related revenue reaching €1.2 trillion. To capture this growth, Volkswagen created the software unit CARIAD to develop a common software platform for the Volkswagen Group.

CARIAD’s first platform release, E3 1.1, was deployed on Volkswagen’s ID.3 and enabled OTA updates. The E3 1.2 platform added an integrated infotainment system and was planned for brands such as Audi and Porsche. The next-generation E3 2.0 platform, originally planned for 2025 on the SSP vehicle platform, has been delayed and may reach production closer to 2030. E3 2.0 is intended to include the VW.OS vehicle operating system, L3–4 autonomous driving functions, and automated charging management.

Volkswagen views E3 2.0 as a tool to monetize software, sell software platforms externally, and sell data collected from vehicles. In June 2023 CARIAD launched an app store for the group, developed with Harman, enabling third-party app providers to distribute applications for Volkswagen Group vehicles. However, if each OEM operates a distinct app store with unique APIs, app providers will face fragmentation and inefficiency, potentially limiting available services and affecting vehicle appeal.

Toyota: Arene OS and software-led value

Toyota has said the next-generation EV it plans to launch around 2026 will derive roughly two-thirds of its value from electronics and software rather than the vehicle platform. Toyota aims to make that vehicle its first software-defined vehicle, centered on its vehicle OS, Arene OS.

Toyota plans a global software development organization involving Woven by Toyota and Toyota Connected and has outlined staff targets to scale in-house software capability. Arene OS is designed to run on integrated ECUs and act as middleware to host multiple virtual ECUs, enabling OTA updates and post-sale feature additions. Arene OS comprises a set of tools for efficient development and evaluation of automotive software, an SDK for integrating advanced software, and interaction mechanisms (UI) between people, cars, and society. Toyota’s Arene OS also includes an online services platform component to receive services from other industries such as logistics and utilities, extending vehicle potential beyond traditional boundaries.

Sony Honda Mobility (AFEELA) software strategy

Sony and Honda established Sony Honda Mobility (SHM) in 2022. Their AFEELA prototype debuted at CES 2023 and targets SDV capability with continuous software updates via 5G. SHM positions the vehicle around three values: Autonomy (continually upgradable autonomy), Augmentation (extending bodily and temporal reach), and Affinity (integration between car, people, and society). AFEELA is planned for preorders in 2025 and deliveries beginning in spring 2026, subject to progress.

The prototype features 45 cameras and sensors and a SoC capability projected up to 800 TOPS. For reference, L2+ ADAS functionality typically requires on the order of 10 TOPS for highway-level perception, so 800 TOPS implies significant aggregate compute across domains.

SHM intends to combine Honda’s vehicle platform and operating system technology with Sony’s strengths in UX, audio, and content. Honda has been developing its own vehicle OS and expects to deploy it on large EVs in North America from 2025. SHM has engaged software partners such as Elektrobit for cockpit software and Epic Games for advanced in-vehicle experiences. The AFEELA electronics architecture described by SHM maps ADAS to Snapdragon Ride, in-cabin UX to Snapdragon Cockpit Platform, cloud connectivity to Snapdragon Car-to-Cloud services, and connectivity to the Snapdragon Automotive Connectivity Platform.

Tesla: leading through OTA and data

Tesla has been a pioneer in software-defined vehicle concepts. It introduced OTA software updates in 2012 and uses vehicle data collection at scale to improve software and perception models. Tesla demonstrates the consumer-facing potential of software through features such as holiday-themed “Easter eggs” and comfort modes like “Camp Mode,” which maintains climate control and power to USB and 12V outlets while parked.

Tesla frequently updates core features such as its Full Self-Driving (FSD) software; in 2023 alone Tesla issued more than ten updates in the U.S. Improving deep learning accuracy requires massive datasets, and Tesla collects large volumes of image and telemetry data from its fleet, especially when vehicles are connected to the Tesla Supercharger network.

Tesla’s integrated ECU approach consolidates functions into fewer domain controllers, which simplifies OTA verification compared to distributed ECUs across body locations. While Tesla has not yet widely deployed hypervisor-based virtualization, its early adoption of integrated architectures and extensive OTA practice positioned it years ahead of many competitors in delivering software-driven features. Privacy and data-collection strategies remain sensitive for many automakers, but Tesla’s approach highlights the potential advantage of a vertically integrated OTA and data collection model.