How Do Capacitors Contribute to Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC)?

Capacitors are fundamental components in the field of electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), serving a critical role in managing and mitigating electromagnetic interference (EMI) and enhancing the immunity of electronic devices. Their diverse applications ensure that electronic systems operate reliably within their intended electromagnetic environments, preventing both self-interference and susceptibility to external disturbances.

From filtering unwanted signals to stabilizing power supplies and protecting against electrostatic discharge, capacitors are versatile tools for EMC engineers. Their proper selection and strategic placement are paramount to achieving a robust and compliant electronic design, ensuring different parts of a system coexist without mutual interference.

Primary Functions of Capacitors in EMC

● Filtering Unwanted Signals: Capacitors are core elements in various filter circuits. When positioned on signal or power lines, they effectively shunt high-frequency noise and EMI to ground, thus preserving the integrity of both power delivery and data signals.

● Power Supply Decoupling: In complex circuits, capacitors are essential for decoupling power supplies. This ensures a stable and clean power source reaches all components, preventing noise on power rails from contaminating sensitive circuitry.

● Suppressing RF Interference: High-frequency radio frequency (RF) interference can severely impact wireless communication and other high-frequency systems. Capacitors are utilized to absorb and suppress these RF signals, preventing their entry into or exit from a device.

● ESD Protection: In environments prone to electrostatic discharge (ESD), capacitors can absorb and safely dissipate transient electrostatic energy, thereby shielding sensitive components from damage.

● Differential-Mode Noise Filtering: For analog applications, capacitors are frequently employed to filter differential-mode signals, effectively reducing noise impact on the intended signal.

● Common-Mode Interference Rejection: Capacitors also play a role in common-mode rejection circuits, which are designed to mitigate common-mode signals—interference that affects both conductors of a circuit simultaneously.

Understanding Capacitor Self-Resonance and Its Implications for EMC

Ideal capacitors are theoretical constructs; in reality, every capacitor exhibits parasitic inductance and resistance. When integrated into a circuit, a real-world capacitor behaves as an ideal capacitance in series with an Equivalent Series Inductance (ESL) and an Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR). This non-ideal behavior significantly alters its frequency characteristics, particularly relevant in EMC applications.

For instance, a multi-layer ceramic capacitor (MLCC) on a PCB may have an ESL of nearly 5 nH and an ESR of around 30 mΩ. Consequently, its frequency response deviates from a simple low-pass filter, instead exhibiting an insertion loss characteristic that resembles a band-stop filter centered at its self-resonant frequency (SRF).

The Phenomenon of Anti-Resonance in Parallel Capacitors

Connecting multiple capacitors in parallel, a common practice for broadband decoupling, can introduce an anti-resonance problem. This occurs due to the interaction between their individual ESL and ESR values. Within certain frequency ranges, specifically between approximately 15 MHz and 175 MHz as an example, the combined impedance of parallel capacitors can actually become higher than that of a single large capacitor. This impedance peak, often observed around 150 MHz, results from resonance between the capacitors. During such an anti-resonance event, only a minimal amount of energy from other parts of the system can be effectively shunted to the ground plane, compromising decoupling effectiveness.

Capacitor Parameters Beyond Basic Capacitance

While engineers typically focus on capacitance, voltage rating, package size, and temperature characteristics for general circuit design, high-speed, power, or critical clock circuits demand a deeper understanding. Here, a capacitor is more accurately modeled as an equivalent circuit comprising capacitance, resistance, and inductance. The performance of this equivalent circuit is influenced by numerous factors, necessitating consideration of these equivalent parameters at specific operating frequencies during capacitor selection. For example, a 1 µF Murata capacitor, at its resonant frequency, might exhibit an equivalent capacitance of 602.625 nF, an ESR of 11.5356 mΩ, and an ESL of 471.621 pH—values that significantly differ from its nominal ideal performance. Relying solely on copied reference designs without understanding these nuances can lead to suboptimal or even failing power delivery networks (PDNs) due to varying PCB layer stacks and current plane configurations across different products.

How ESR and ESL Influence Parallel Capacitor Performance

The Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR) and Equivalent Series Inductance (ESL) are critical parasitic parameters that profoundly affect a capacitor's performance, especially when multiple capacitors are connected in parallel for EMC purposes. Understanding their impact is essential for effective decoupling and filtering.

Impact of ESR on Parallel Capacitor Frequency Response

The magnitude of the impedance peak at anti-resonance is inversely proportional to a capacitor's ESR. As modern board designs and component technologies advance, capacitors tend to have lower ESR values. While lower ESR generally improves performance at series resonance (reducing minimum impedance), it can paradoxically increase the impedance peak at anti-resonance. The exact shape and position of this parallel resonance peak are highly dependent on the PCB layout and the specific capacitor choices.

Key principles regarding ESR:

● A decrease in ESR reduces impedance at the series resonant point but elevates impedance at the anti-resonant point.

● When 'n' identical capacitors are connected in parallel, the minimum impedance achieved can be lower than ESR/n.

● The lowest impedance point in a multi-capacitor parallel arrangement does not necessarily coincide with the self-resonant frequency of any single capacitor.

● For optimal performance with a given number of capacitors, it is better to use a range of capacitance values, each with moderate ESR, rather than a few values all possessing very low ESR.

Impact of ESL on Parallel Capacitor Frequency Response

ESL is influenced by the capacitor's physical package and internal construction. This parasitic inductance, in conjunction with the capacitance value, defines the self-resonant frequency of a single capacitor and also the anti-resonant frequency range observed when capacitors are paralleled. In practical EMC design, prioritizing capacitors with low ESL is crucial for effective high-frequency performance.

Strategic Capacitor Selection for Effective EMC

Choosing the right capacitors is a critical step in effective EMC design. The application dictates the type, dielectric, and specific characteristics needed to achieve optimal filtering and noise suppression.

Capacitor Types for RF and EMI Filtering

● RF Design: For radio frequency applications, ceramic, polyester, and polystyrene film capacitors are generally excellent choices due to their stable characteristics at higher frequencies.

● EMI Filters: For general EMI filtering, the exact dielectric material is less critical. Common dielectrics like X7R, Y5V, and Z5U are often suitable. Parameters such as absolute capacitance value, temperature coefficient, and voltage coefficient are typically not as crucial as in precision analog circuits.

Different types and capacitance values offer varying filtering ranges. For example, within the same 0805 package, a 0.01 µF ceramic capacitor typically exhibits superior high-frequency filtering compared to a 0.1 µF capacitor. For PCBs operating at frequencies above 50 MHz, it's often more beneficial to use 0.01 µF filter capacitors instead of the more commonly chosen 0.1 µF.

Designing with Power Supply Input and Output Capacitors

Capacitors placed on the input and output loops of a power module are often referred to as filter capacitors. Their primary function is to maintain stable input and output voltages, which is vital for the integrity of the power supply and connected circuits. A fundamental principle for their placement in power modules is "large to small"—capacitors should be arranged in descending order of capacitance value along the direction of current flow.

Furthermore, in power supply design, it is imperative to ensure that PCB traces and copper pours are sufficiently wide and that an adequate number of vias are used to safely handle the required current. The width of traces and the quantity of vias must be carefully evaluated based on the current magnitude to prevent voltage drops and localized heating.

Power Supply Input Capacitor Considerations

The input capacitor of a power supply forms a critical current loop with the switching circuit of a DC-DC converter. This loop experiences significant current fluctuations, with amplitudes reaching the output current (Iout) at the switching frequency. These rapid current changes, characterized by high di/dt, are inherent to the DC-DC chip's switching operation. For synchronous buck converters, where the freewheeling current path typically includes the chip's GND pin, the input capacitor should be connected between the chip's GND and Vin pins using the shortest and widest possible trace paths. Minimizing the physical area of this high di/dt current loop is crucial, as a smaller loop area directly correlates with reduced electromagnetic radiation.

Optimizing Decoupling and Bypass Capacitors for Performance

Decoupling and bypass capacitors are essential for maintaining stable power delivery to integrated circuits (ICs) and suppressing noise. Their effective implementation requires careful consideration of capacitor characteristics and PCB layout.

Key Principles for Decoupling Capacitor Selection and Placement

● Resonance Characteristics: Select capacitors whose self-resonance characteristics, typically provided in datasheets, align with the design's clock speed and target noise frequencies.

● Broadband Coverage: Incorporate multiple capacitors to cover a broad frequency range. For example, a 22 nF capacitor might have an SRF near 11 MHz and provide useful impedance (Z < 1 Ω) from 6 MHz to 40 MHz. Using multiple capacitors can ensure adequate decoupling across a wider band.

● Proximity to ICs: Place at least one decoupling capacitor as close as possible to each power pin of an IC. This minimizes parasitic impedance in the power delivery path.

● Layer Placement: Whenever feasible, place bypass capacitors on the same PCB layer as the IC itself. Crucially, the Vcc connection from the capacitor to the Vcc plane should ideally be at a single point. This forces noise from both inside and outside the IC to pass through a single via to the power plane, where the via's inherent impedance helps to contain noise spread.

● Power Plane Partitioning: In multi-clock systems, partitioning the power plane can effectively isolate noise. Each partition can then be decoupled with capacitors of appropriate values, preventing noise from affecting sensitive components in other board areas.

● Wide Frequency Range Bypassing: For systems with widely varying clock frequencies, selecting a single bypass capacitor is challenging. A practical solution involves paralleling two capacitors with a capacitance ratio of approximately 2:1. This strategy creates a broader low-impedance region and extends the effective bypass frequency range. While an impedance peak still occurs, its magnitude is reduced (e.g., less than 15 Ω), and the usable frequency range (e.g., impedance < 15 Ω) is significantly widened (e.g., from 3.25 MHz to 100 MHz). This multi-capacitor approach is best reserved for situations where a single IC demands a wide bypass frequency range that a lone capacitor cannot provide, always ensuring the capacitance values maintain a 2:1 ratio to keep the impedance peak within acceptable limits.

● High-Speed ICs: High-speed IC power pins generally require a sufficient number of decoupling capacitors, ideally one per pin. In space-constrained designs, some may be judiciously omitted.

● Small Capacitance Values: Decoupling capacitors for IC power pins are typically small (e.g., 0.1 µF or 0.01 µF) and come in small packages (e.g., 0402 or 0603).

● Layout Rules for Decoupling:

○ Close Proximity: Place capacitors as close as possible to the power pin; otherwise, their decoupling effectiveness diminishes. The principle of a limited decoupling radius must be strictly observed.

○ Short, Wide Traces: The traces connecting the decoupling capacitor to the power pin should be as short and wide as possible (e.g., 8-15 mils) to minimize inductance and ensure power integrity.

○ Nearby Vias: After fanning out from the capacitor pads, the power and ground traces should connect to their respective planes via nearby vias. These traces should also be widened, and larger vias (e.g., 10-mil instead of 8-mil) should be used if space permits.

○ Minimize Loop Area: Always strive to keep the decoupling current loop area as small as possible. This is crucial for reducing radiated emissions.

○ BGA Placement: For BGA packages, decoupling capacitors are usually placed on the underside of the BGA. Due to high pin density, the number of capacitors may be limited, but designers should place as many as practically possible.

Effective Energy Storage Capacitor Design

Energy storage capacitors, often referred to as bulk capacitors, are crucial for maintaining stable supply voltage during sudden, heavy load transitions. They serve as local reservoirs of charge, preventing voltage sags that could affect system performance. These capacitors can be categorized based on their application level:

Categories of Energy Storage Capacitors

● Board-Level Storage Capacitors: These ensure that the overall supply voltage across the entire PCB remains stable when the board's total load changes rapidly. For high-frequency, high-speed boards, it is advisable to strategically distribute several larger value tantalum capacitors (e.g., 1 µF, 10 µF, 22 µF, 33 µF) to maintain a consistent voltage level across the board.

● Device-Level Storage Capacitors: These are placed near individual devices to prevent local supply voltage drops during rapid load changes specific to that component. For high-frequency, high-speed devices with significant power consumption, it is recommended to place 1-4 larger value capacitors (e.g., 1 µF, 10 µF, 22 µF, 33 µF) in their immediate vicinity.

Design Guidelines for Storage Capacitors

● Single Capacitance Value per Rail: When a board has multiple supply voltages, it is generally best to use a single, consistent capacitance value for the storage capacitors associated with each individual voltage rail. Surface-mount tantalum capacitors are frequently chosen, with values like 10 µF, 22 µF, or 33 µF selected based on the specific current demands.

● Even Distribution: Group chips by their respective supply voltages and distribute the storage capacitors evenly within each group to provide consistent local energy reserves.

● Placement Considerations: The primary purpose of a storage capacitor is to deliver energy quickly when an IC requires it. While storage capacitors typically have larger capacitance values and packages, they can be placed slightly further from the device than decoupling capacitors, though still not excessively far.

Principles for Capacitor Fanout

● Minimize Parasitic Inductance: Keep traces connecting to capacitors short and wide to minimize parasitic inductance, which is crucial for rapid energy delivery.

● Multiple Vias for High Current: For storage capacitors or components handling high currents, use multiple vias to reduce impedance and improve current flow.

● Optimal Via Placement: While via-in-pad offers the best electrical performance, practical manufacturing constraints (e.g., cost, complexity) must be carefully weighed.

Employing Capacitors Effectively in EMC Filter Circuits

EMC filters are typically designed as low-pass filters, utilizing inductors (L) and capacitors (C) to block high-frequency noise while allowing desired signals or DC power to pass. The effectiveness of an LC filter is highly dependent on its structure and, critically, the impedance of the network it connects to. For instance, a simple single-capacitor filter performs well in high-impedance circuits but poorly in low-impedance ones. While traditional filter characteristics are often described with 50-ohm terminations, real-world source and load impedances (Zs and Zl) are usually complex and unknown across the relevant frequency spectrum. If either or both ends of the filter connect to reactive components, resonance can occur, potentially transforming insertion loss into insertion gain at certain frequencies, which is counterproductive.

Within a signal path, L and C form a low-pass filter. Since the exact source and load impedances at specific frequencies are often unpredictable, it is vital to avoid component value combinations that inadvertently filter out the desired signal components. A common pitfall for engineers is to indiscriminately use standard capacitor values like 1 nF or 100 nF without proper calculation, which can sometimes worsen performance.

Understanding Capacitor Resonance in Filters

Capacitor resonance typically arises from the interaction between the capacitor's inherent capacitance and the equivalent inductance of its leads or connecting traces. The resonant frequency (F) is determined by the formula: F = 1 / (2 * π * √(LC)).

● Series LC Resonance: In a series LC circuit, resonance results in minimum impedance, acting like a short circuit.

● Parallel LC Resonance: In a parallel LC circuit, resonance results in maximum impedance, behaving like an open circuit.

When L and C components are arranged in a shunt configuration (capacitor to ground), they form a series resonant circuit. If the resonant frequency of this LC combination matches the interference frequency targeted for filtering, the path to ground acts as a short circuit, effectively shunting the noise.

Consider a scenario where a useful signal operates at 5 MHz, and an interference signal needs to be filtered at 10 MHz, using a 1 µH inductor (L). If an arbitrary 1000 pF capacitor (C) is selected, the resonant frequency calculates to approximately 5.03 MHz. At this frequency, the LC combination forms a short to ground, inadvertently shunting the valuable 5 MHz signal, causing circuit failure. Instead, the capacitor value should be carefully chosen to resonate at the interference frequency. To achieve a 10 MHz resonance with a 1 µH inductor, the required capacitance is 253.3 pF; the closest standard value should be selected. Furthermore, minimizing ESL by using short leads for through-hole components or, ideally, surface-mount devices (SMDs) is crucial. This example underscores that while experience is valuable, relying solely on empirical values can be detrimental, especially when harmonics of desired signals are present. Always calculate the required component values.

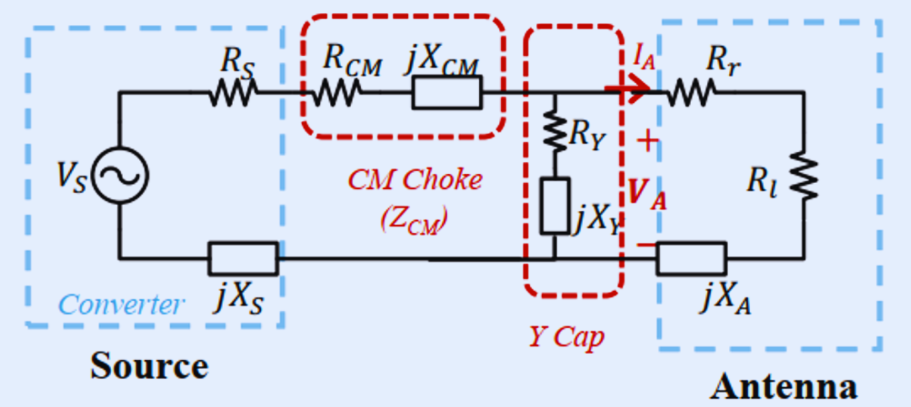

When filtering noise on a wire harness, using a low-cost capacitor without proper consideration can sometimes redirect interference to other paths, inadvertently creating an antenna effect and increasing radiated emissions. It's critical to understand that a capacitor primarily transfers energy; it does not dissipate it. A capacitor is only effective for filtering when connected to a low-impedance network. This energy-transfer characteristic is frequently overlooked, with engineers often assuming a connection to ground is a universal solution.

Differentiating Common-Mode and Differential-Mode Capacitors

In EMC, understanding the roles of common-mode and differential-mode capacitors is crucial for effectively addressing different types of noise. These distinctions are particularly relevant in differential signal paths, differential amplifiers, and communication systems.

Common-Mode Capacitors

A "common-mode capacitor" generally refers to the capacitance between the common-mode portion of a differential signal and ground. A differential signal intrinsically comprises two elements: a differential-mode signal (the difference between the two input signals) and a common-mode signal (the average or shared component of the two signals). While ideally a differential amplifier only amplifies the differential-mode signal and rejects the common-mode signal, real-world circuits are imperfect.

Common-mode capacitance introduces several problems:

● Common-Mode Noise Amplification: If common-mode noise exists on the input signals, this capacitance can cause the noise to be amplified, degrading circuit performance.

● Reduced CMRR: The Common-Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR), a key metric for differential amplifiers, measures their ability to reject common-mode signals. Common-mode capacitance can significantly degrade the CMRR.

In filter design, differential-mode inductors are often not used separately because common-mode chokes inherently provide some differential-mode inductance due to winding imbalances. However, if differential-mode interference is severe, a dedicated differential-mode inductor may be necessary.

Differential-Mode Capacitors

Capacitors inherently exhibit high impedance at low frequencies and progressively lower impedance at high frequencies. This characteristic is leveraged in filters where the low impedance of a capacitor at high frequencies is used to short-circuit differential-mode interference. For instance, a capacitor's impedance is almost infinite at 50 Hz, offering virtually no attenuation. However, at 500 kHz, its impedance becomes very low. If a differential-mode current at 500 kHz encounters a 50-ohm load and a parallel capacitor with an impedance of just 0.05 ohms, nearly all the current will be shunted by the capacitor.

In this scenario, the capacitor shunts 99.9% of the differential-mode interference current, allowing only a mere 0.1% to reach the load. This effectively provides approximately 30 dB of attenuation for the 500 kHz differential-mode interference.