Digital imaging in the 21st century has enabled advanced diagnostic capabilities, electronic image archiving, and on-demand retrieval. Since the emergence of digital medical imaging in the early 1970s, the importance of digital imaging has grown steadily. New advances in mixed-signal design for semiconductor devices have allowed imaging systems to achieve unprecedented electronic packaging density, driving major progress in medical imaging. At the same time, embedded processors have greatly improved medical image processing and real-time image display, enabling faster and more accurate diagnoses. The convergence of these technologies and emerging electronic health record standards has supported improvements in patient care.

This article reviews electronic design challenges and recent developments for different imaging modalities, including digital X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound systems.

Digital X-ray Systems

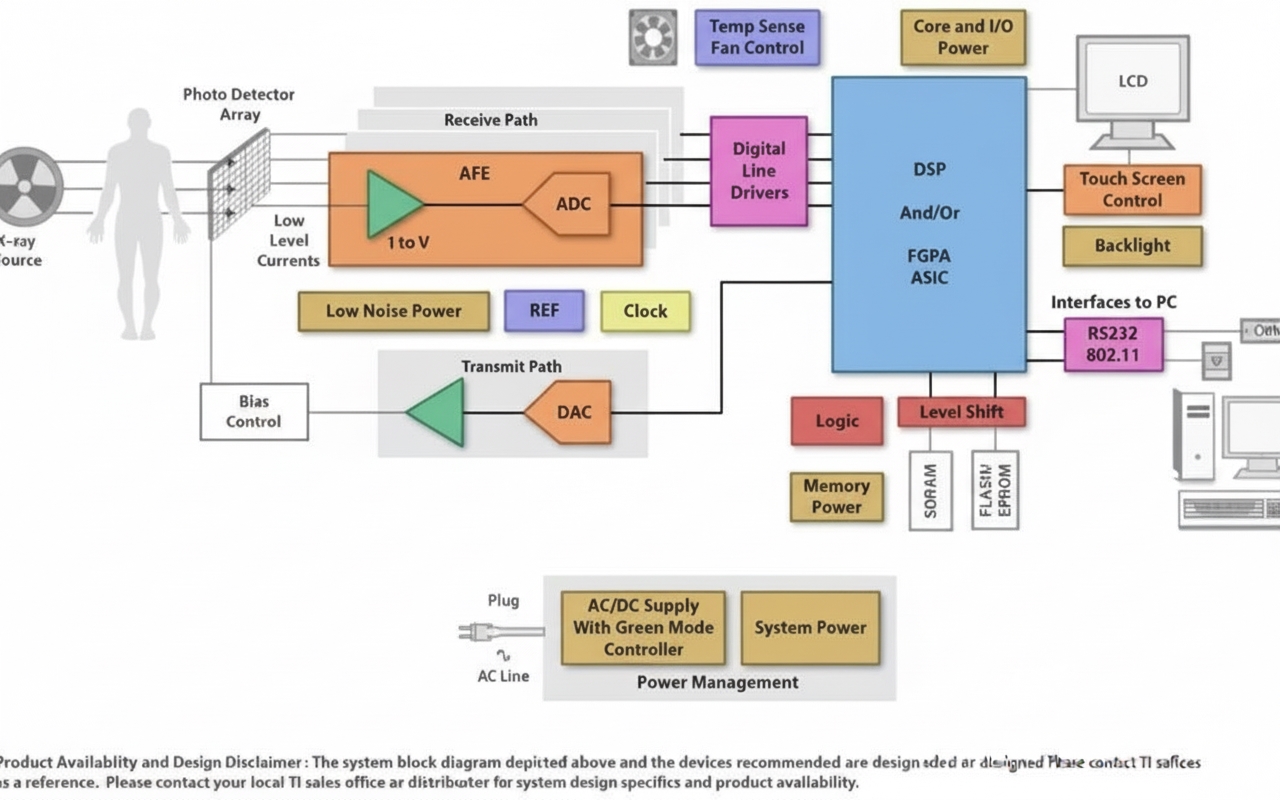

Conventional X-ray systems use a film/screen setup to detect X-rays transmitted through the body. In contrast, the digital X-ray detector signal chain includes a photodetector array that converts radiation into charge, followed by charge integrator circuits and analog-to-digital converter (ADC) circuits to digitize the signals. Figure 1 shows an example block diagram of a typical digital X-ray system.

Figure 1 Example digital X-ray system block diagram

The performance of a digital X-ray system is closely related to the noise performance of the charge integrators and ADC modules. To achieve higher image quality at low power, a system that supports a large number of signal channels sets a high bar for electronic integration. Many high-performance analog components in the detector system, together with embedded processors that perform advanced image processing, provide several advantages over traditional X-ray systems. This combination supports a larger dynamic range, enabling better image contrast and lower patient X-ray exposure, while producing digitally storable and transferable images.

Ultrasound Systems

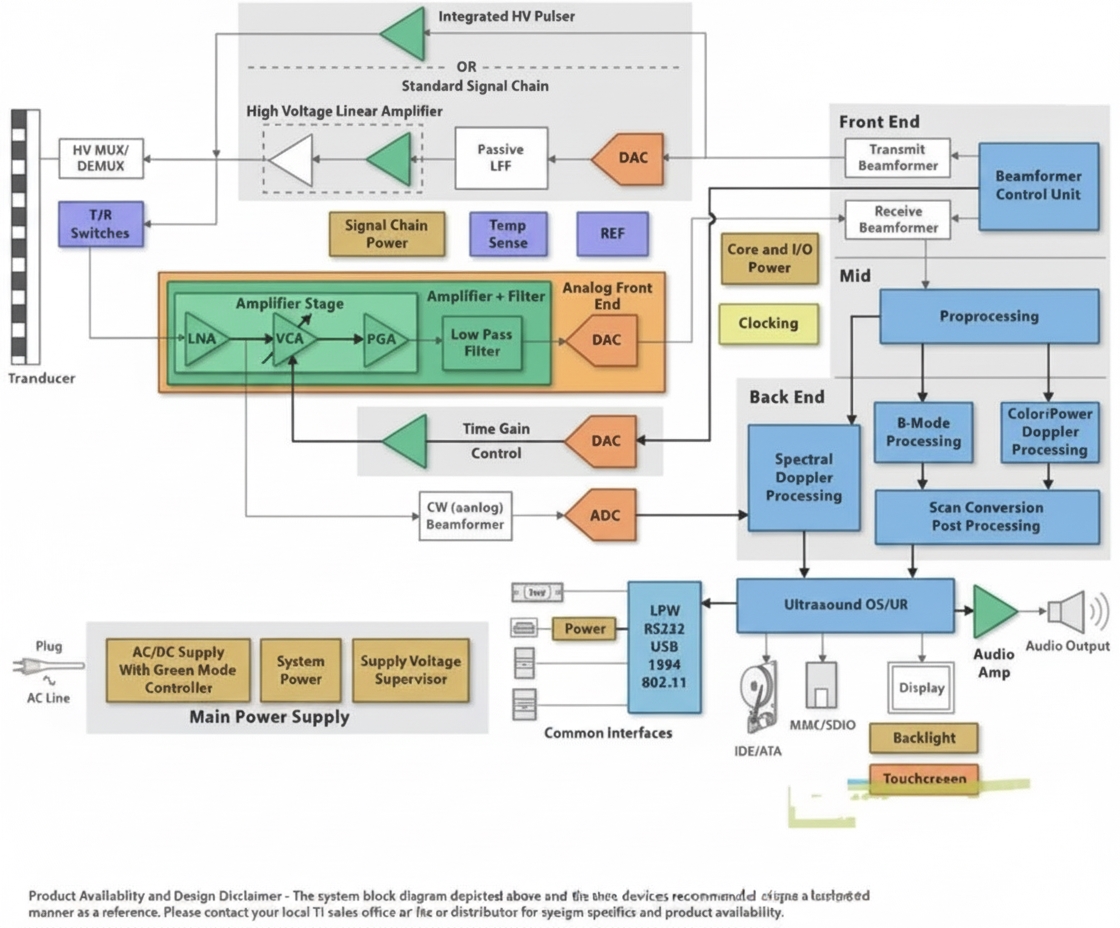

The receive-channel signal chain for ultrasound systems typically includes a low-noise amplifier (LNA), variable-gain amplifier (VGA), low-pass filter (LPF), and a high-speed, high-precision ADC. These components are followed by digital beamforming, image and Doppler processing, and other signal-processing software, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Example ultrasound system block diagram

The noise and bandwidth characteristics of the signal-chain components define the upper bound of system performance. In addition, there is demand to integrate more high-performance channels into a smaller area while reducing total system power. A typical handheld ultrasound system might have about 16 to 32 channels, while high-end systems may use 128 or more channels to achieve higher image quality. Reducing the printed circuit board (PCB) area occupied by these array channels requires integrating as many channels as possible into the analog front-end ICs. Total system power is another critical metric for handheld devices. Integrating the receive electronics directly into the probe is another innovation.

This integration shortens the distance between low-voltage analog signal sources in the probe and the LNAs, reducing signal loss. Integration can also increase the number of probe elements, enhancing 3D imaging. Beyond analog signal-chain considerations, high-performance, low-power embedded processors can perform beamforming and image processing for portable devices faster and more efficiently than before.

MRI

Whole-body MRI systems may use coil arrays with up to 76 elements or channels. In advanced MRI architectures, low-voltage analog inputs are routed from limb coils to front-end amplifiers through carefully designed medical PCB assembly using long coaxial cables. Two key requirements for the MRI receive chain are high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), typically on the order of 84 dB (about 14 bits), and very high total system dynamic range, on the order of 150 dB/Hz. Achieving high SNR requires an ultra-low-noise, high-performance front-end amplifier implemented on a medical PCB with optimized grounding, shielding, and impedance control. Techniques such as dynamic gain switching or analog input compression can help meet the high dynamic range requirement.

Increasing the number of coils in an MRI system can improve image coverage and reduce scan time. More coils may require optimized communication between coils and preamplifiers, and when using high-speed digital or optical links, further system-level optimization is needed. Higher integration may shift system partitioning, placing electronics closer to the coils. This may require nonmagnetic semiconductor IC packaging and stricter constraints on power consumption and area. Successfully addressing these requirements can reduce input-signal attenuation and yield higher-quality medical images.

Suggested Reading: Nuclear Medicine Imaging Devices: Types, Features and Process

Conclusion

Digital imaging remains one of the most active areas of development in medical technology. Advances in IC analog/mixed-signal functionality and embedded processing continue to drive improvements. These technologies enhance imaging system performance and improve the quality of diagnostic and clinical care delivered to patients.