1. 6G concept

6G (sixth-generation wireless technology) will succeed 5G cellular technology. 6G networks will use frequencies higher than 5G and offer higher capacity and lower latency. One target for 6G networks is to support 1 microsecond or even sub-microsecond latency communications.

6G communications are expected to support five application scenarios: enhanced mobile broadband Plus (eMBB-Plus), large communications (BigCom), secure ultra-reliable low-latency communications (SURLLC), three-dimensional integrated communications (3D-InteCom), and unconventional data communications (UC-DC).

5G began deployment in 2019 and is expected to remain a primary mobile communication technology through at least 2030. Initial 6G deployments may start appearing in the 2030–2035 timeframe.

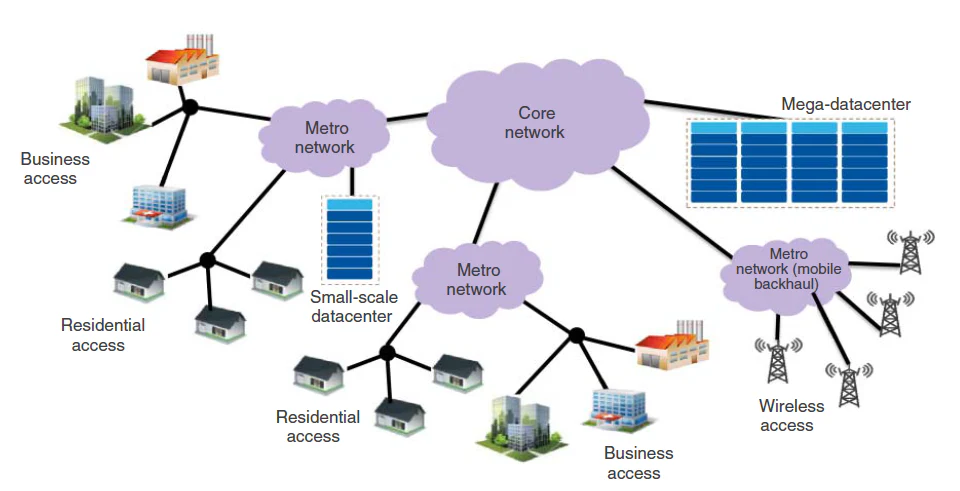

6G aims to create a fully connected communication world integrating terrestrial, satellite, and maritime links, extending coverage into current blind spots such as deserts, uninhabited areas, and open oceans.

Projected 6G use cases include space communications, intelligent interaction, tactile internet, emotional and haptic exchange, multisensory mixed reality, machine-to-machine collaboration, and fully automated transportation.

2. 6G evolution

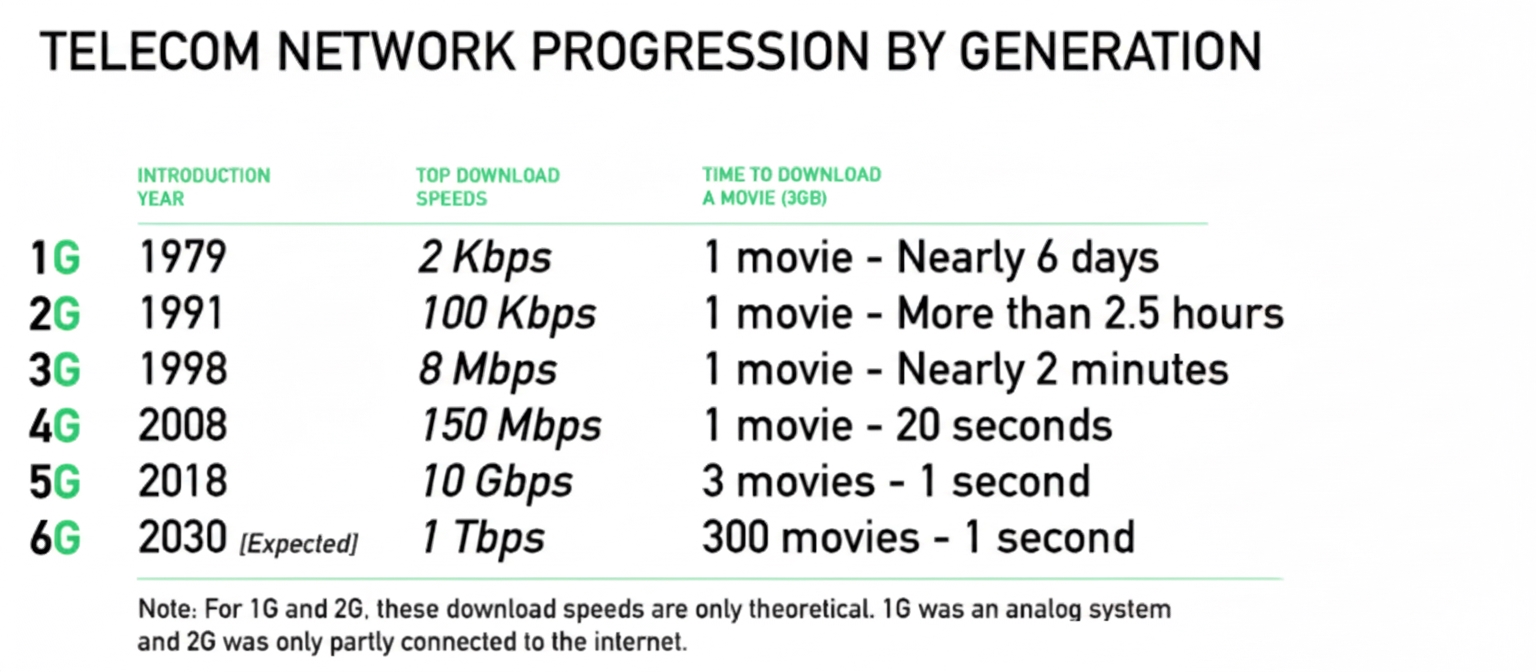

Since the first public cellular service initiated by NTT in December 1979, mobile communication technology has advanced to a new generation roughly every decade.

From 1G to 2G, voice calls dominated and simple email became possible. Starting with 3G, data communication and multimedia such as photos, music, and video became viable on mobile devices. From 4G, using Long Term Evolution (LTE) technology, high-speed communications above 100 Mbps enabled explosive smartphone adoption, approaching peak speeds near 1 Gbps.

5G network throughput far exceeds previous cellular generations, reaching up to 10 Gbit/s with network latency below 1 ms. 6G is expected to support speeds on the order of 1 TB/s. That level of capacity and latency will extend 5G application performance and broaden the functional scope to support innovations in wireless cognition, sensing, and imaging.

Mobile communication systems have advanced roughly every 10 years, while major shifts in mobile services follow cycles of about 20 years. The wave triggered by 5G is expected to continue through 5G evolution and 6G technologies, supporting industry and society into the 2030s.

Past cellular generations each introduced representative technologies. Since 4G, OFDM-based radio access technologies have combined multiple new techniques. For 6G, the technological space is expected to become even more diverse, because OFDM-based designs have approached the Shannon limit in communication performance while use cases and requirements further expand.

Post-5G communication research must account for circuit and device manufacturing capabilities. In 6G, device battery life will require special attention as much as data rates and latency. Future wireless links are also expected to approach wired reliability. Decentralized network management based on blockchain-like techniques is seen as a possible approach to simplifying operations and delivering acceptable performance in 6G.

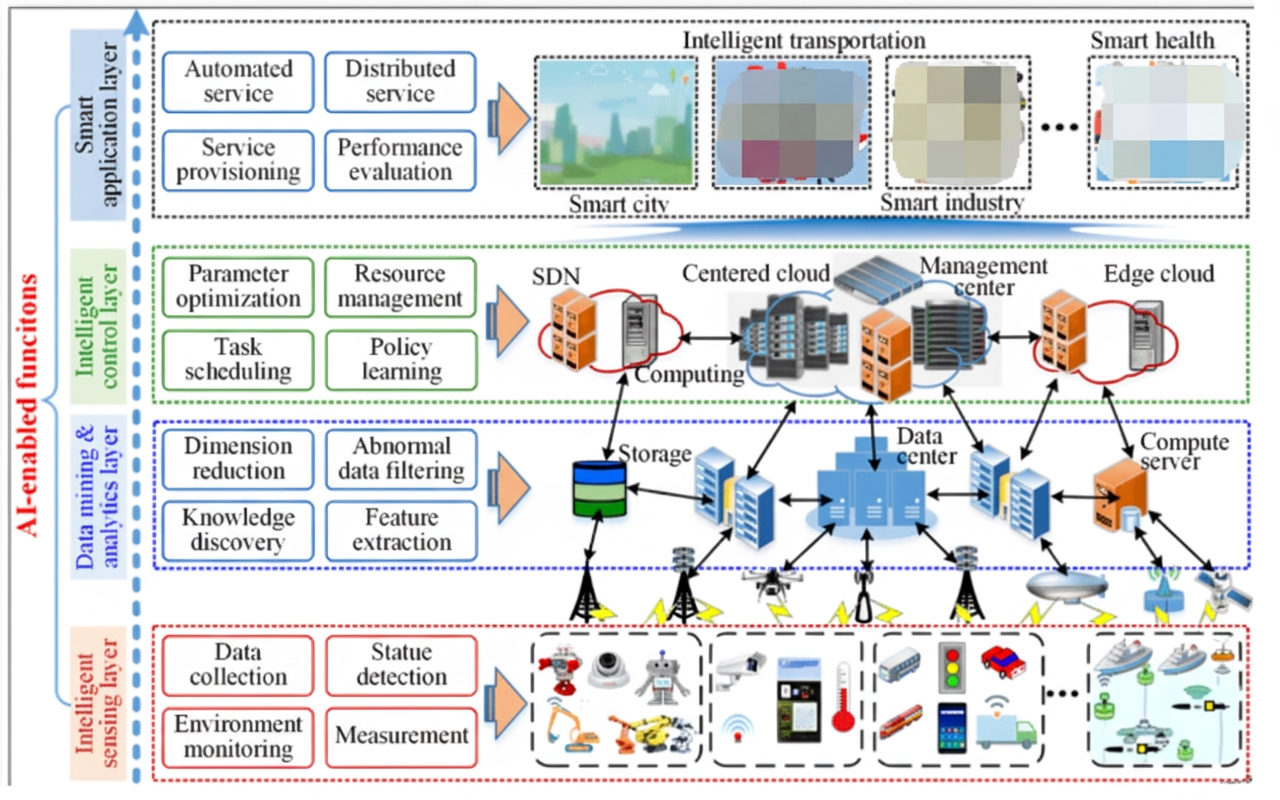

Among candidate 6G technologies, terahertz communications, artificial intelligence (AI), and reconfigurable intelligent surfaces are considered the most transformative. AI-enhanced 6G is expected to deliver features such as self-aggregation, context awareness, and self-configuration, enabling a shift from cognitive radio to intelligent radio. From an algorithmic perspective, machine learning is particularly important to realize AI-driven 6G.

AI-based intelligent 6G network architectures are envisioned to place learning and decision-making capabilities at both distributed radio sites and centralized control centers.

3. 6G key requirements

High security, confidentiality, and privacy

Given limits imposed by Shannon theory, dramatically increasing spectral efficiency at scale is difficult. Instead, new technologies should substantially strengthen security, confidentiality, and privacy in 6G communications. Although new application scenarios will become ubiquitous and important, traditional mobile communications will remain a primary 6G use. Therefore, 6G networks should be human-centered rather than machine-, application-, or data-centered. Accordingly, high security, confidentiality, and privacy should be core 6G features. User experience should be used as a key metric for 6G network performance.

5G networks still use traditional public-key cryptosystems based on RSA for transport security and confidentiality. Under pressures from big data and AI, RSA is becoming less secure. Increasing network throughput, reliability, and supported users is most effectively achieved by densifying networks and using higher frequencies. Physical-layer security techniques and quantum key distribution via visible light communication (VLC) are possible solutions for 6G data security challenges. Advanced quantum computing and quantum communication technologies may also be deployed to provide robust protection against diverse network attacks.

High resilience and full customization

From a user-centric perspective, technological success should not increase financial burden or remove user choice. Therefore, high resilience and full customization should be two important 6G design objectives. Full customization allows users to choose service modes and adjust personal preferences. For example, some users may prefer low-rate but highly reliable data; others may accept less reliability for lower communication costs; some focus only on device energy consumption; others may opt out of intelligent features due to privacy concerns. All users should be able to choose their preferred behavior in 6G without losing rights due to mandatory intelligent features or unnecessary system configurations. Consequently, 6G performance analysis should integrate multiple performance metrics into an overall assessment, rather than treating them independently. User experience should be clearly defined and used as a key performance evaluation metric in the 6G era.

Low power consumption and long battery life

Daily charging demands for smartphones and tablets will persist. To overcome daily charging limitations and enable broader communication services, low power consumption and long battery life are major 6G research priorities. To reduce power usage, user device computation can be offloaded to intelligent base stations with reliable power or to pervasive intelligent radio spaces. Cooperative relaying and network densification will reduce device transmit power by shortening signal hop distances. Various energy-harvesting methods will be applied in 6G, harvesting energy not only from ambient RF signals but also from micro-vibrations and sunlight. Remote wireless charging also appears promising to extend battery life.

High intelligence

High intelligence in 6G will benefit network operation, the radio propagation environment, and communication services, corresponding to operational intelligence, environmental intelligence, and service intelligence. Routine network operations involve many multi-objective optimization problems with complex constraints. Resources such as radio equipment, spectrum, and transmit power must be allocated to achieve satisfactory operational levels. These optimization problems are often hard to solve in real time. With machine learning advances, especially deep learning, base stations or centralized network control centers equipped with GPUs can run learning algorithms to allocate resources efficiently and approach near-optimal performance.

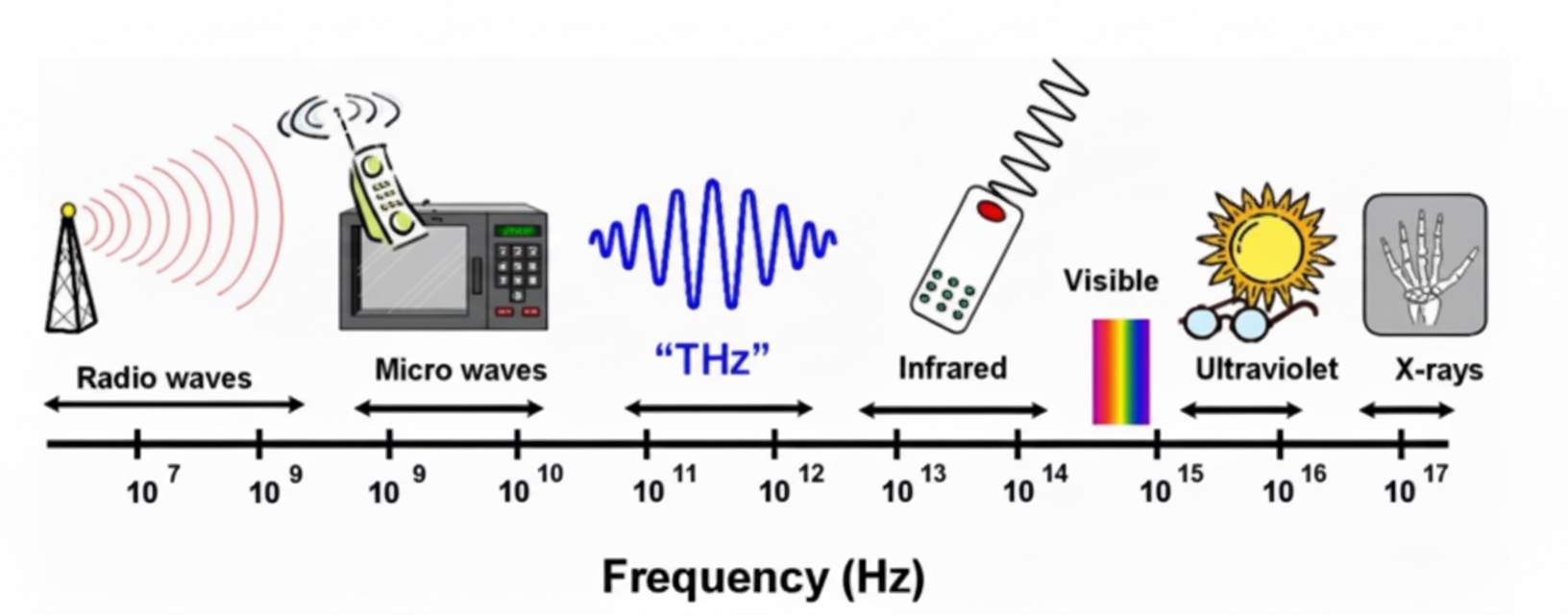

Much larger bandwidth than 5G

The terahertz band, generally defined between 0.1 THz and 10 THz, fills the gap between microwave and optical spectra. Terahertz electronics, photonics, and hybrid electron-photon approaches have now matured. Hybrid terahertz/free-space optical systems are expected to use mixed electron-photon transceivers in 6G, where optical lasers generate terahertz signals or transmit optical signals. Future wireless networks must support much higher data rates and lower latency while serving many more end devices. This will require network topologies composed of many small radio cells. Connecting these cells may require high-performance transmission lines up to terahertz frequencies, and seamless integration with optical networks where possible.

Future wireless links will need to handle tens or hundreds of Gbit/s per link, requiring carrier frequencies in the unallocated terahertz spectrum. Seamless integration of terahertz links with existing fiber infrastructure is important to combine the portability and flexibility of wireless with the reliability and near-unlimited capacity of optical transport. Technically, this requires new devices and signal-processing concepts for direct conversion between optical and terahertz domains.

4. Terahertz-to-fiber conversion

A key 6G technology — terahertz-to-fiber conversion

Terahertz waves refer to electromagnetic waves in the 0.1–10 THz band, with wavelengths of 30 to 3000 micrometers. This spectrum lies between microwaves and far-infrared light, adjacent to millimeter waves at the low end and infrared at the high end, occupying a transition region between macro-scale electronics and micro-scale photonics. Terahertz communications, an underdeveloped band between microwave and optical frequencies, offer abundant spectrum and high data rates, making them a strong candidate for future broadband wireless access (Tb/s-level communications). Terahertz signals have high frequency, short pulses, strong penetration at certain scales, and low energy per photon, minimizing material and biological damage. These properties make terahertz advantageous over microwave and wireless optical communications for high-speed short-range broadband links, secure broadband access, and space communications, while also presenting multiple challenges.

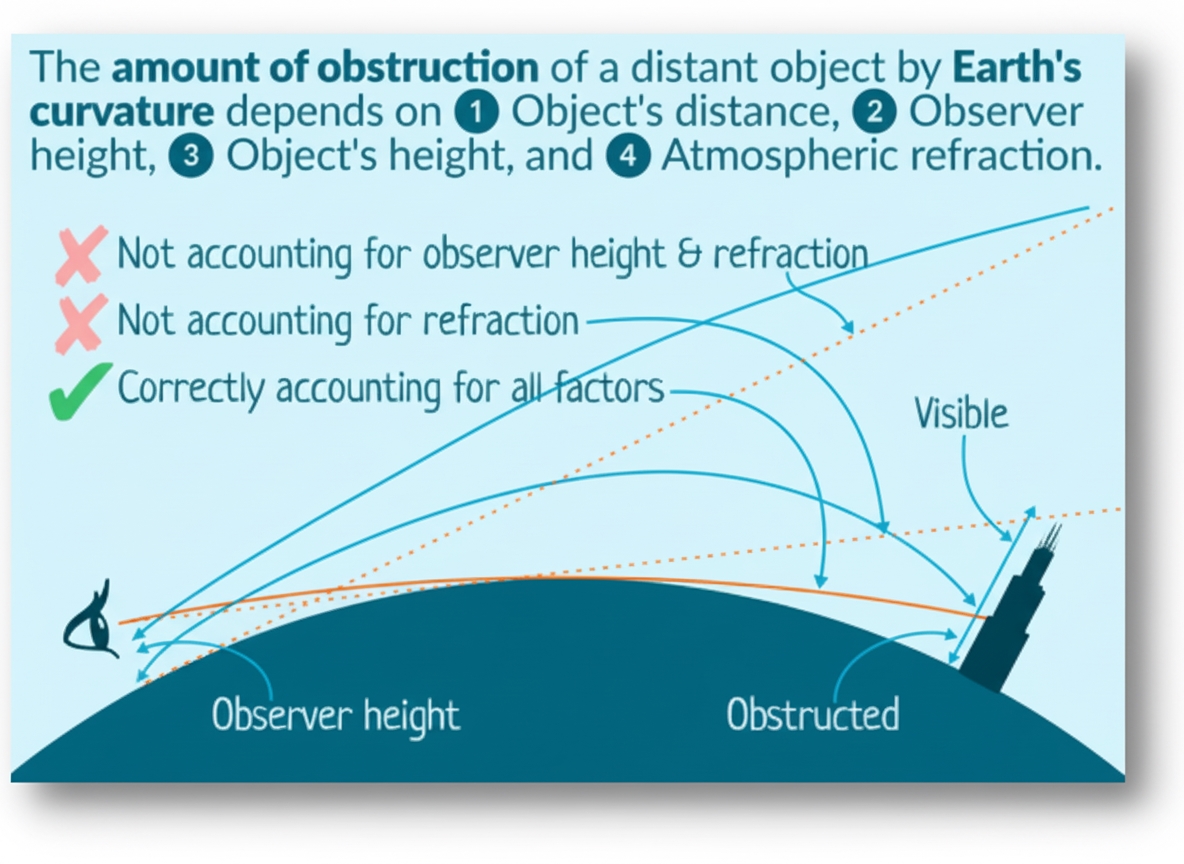

So far, a technological gap remains at the interface between the terahertz spectrum and hard optical transmission lines. How can terahertz (the over-the-air spectrum between microwave and infrared) be connected to transmission lines required for long-distance data transport? On one hand, the earth curvature limits line-of-sight distances, requiring hard wiring for long-haul links. On the other hand, short-range links can be obstructed by environmental factors: as wavelength decreases and frequency rises, blockage by objects or atmospheric conditions like rain or fog becomes more pronounced. To make 6G wireless practical, technical obstacles such as linking terahertz spectra to hard optical transmission lines must be overcome.

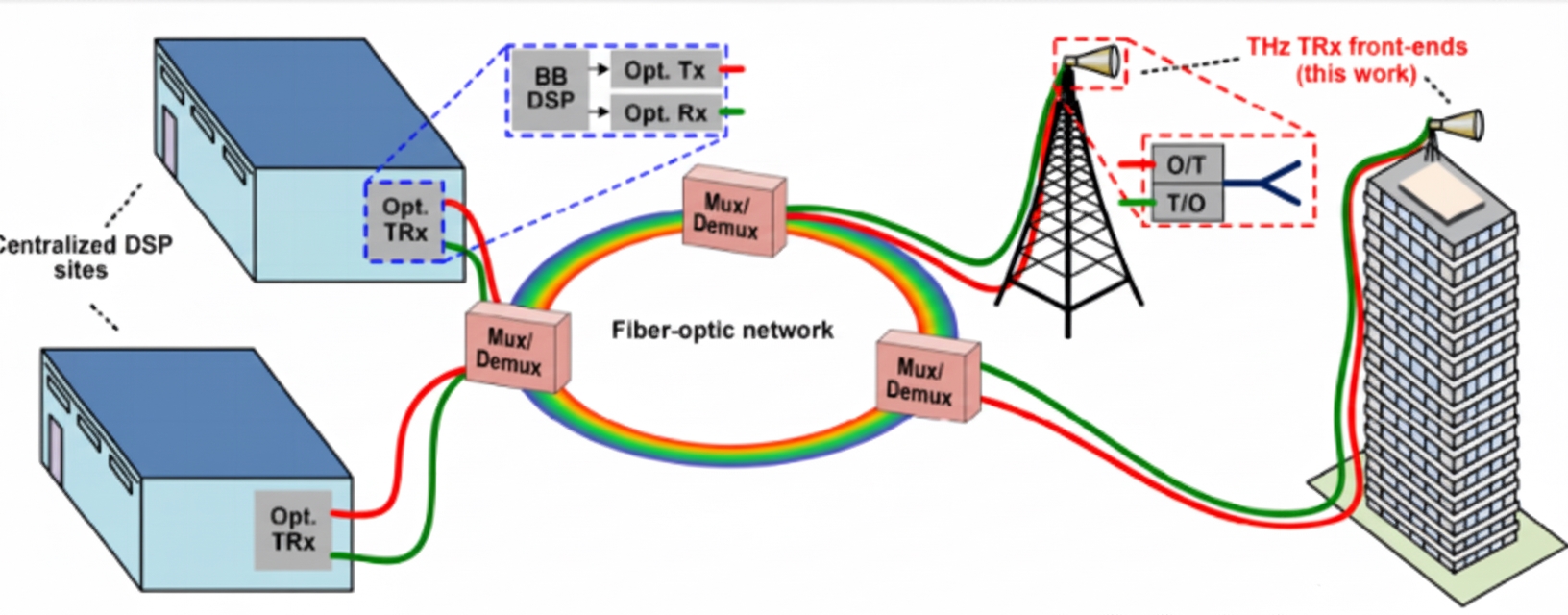

The figure below illustrates how a THz wireless link is seamlessly integrated into fiber infrastructure via direct optical-to-THz (O/T) and THz-to-optical (T/O) conversions.

Seamless integration of a wireless link into an optical network is achieved by performing direct O/T conversion at the THz transmitter and direct T/O conversion at the THz receiver. In a demonstrated setup, the wireless link operated at a carrier frequency of 0.2885 THz with a maximum line rate of 50 Gbit/s over a 16 m bridge distance. The THz signal was generated by O/T conversion in a UTC photodiode. At the receiver, an ultrawideband POH modulator converted the terahertz signal into the optical domain. This concept relies on widely deployed fiber infrastructure to connect distributed THz transceiver front ends to powerful centralized digital signal processing (DSP) sites, using optical carriers to transmit analog baseband waveforms over long distances. Direct O/T and T/O conversion at the TRx front ends is essential for an effective interface between fiber and THz antennas. Direct conversion between analog optical signals and THz waveforms greatly reduces antenna-site complexity and improves scalability for a large number of geographically distributed high-performance THz links or cells. Likewise, moving computationally expensive digital baseband processing to centralized data centers enables unprecedented network scalability, flexible and efficient resource sharing, and improved resilience. Seamless coupling of short-range THz links with long-range fiber networks may be a key step to overcome wireless infrastructure capacity bottlenecks.

The architecture shown in Figure 1a relies on THz transmitter (Tx) and receiver (Rx) front ends that allow direct conversion between optical and THz signals. After the DSP site generates the analog baseband waveform, an optical transmitter (Opt. Tx) modulates it onto an optical carrier at frequency f0 and sends it through the fiber network to the THz Tx. At the THz Tx, a continuous-wave local oscillator (LO) masks the optical signal through a UTC photodiode at frequencies fTx and fLO to convert the optical signal into a terahertz waveform, as shown in Figure 1b. The THz data signal, centered at the difference frequency, is then transmitted over an antenna into free space.

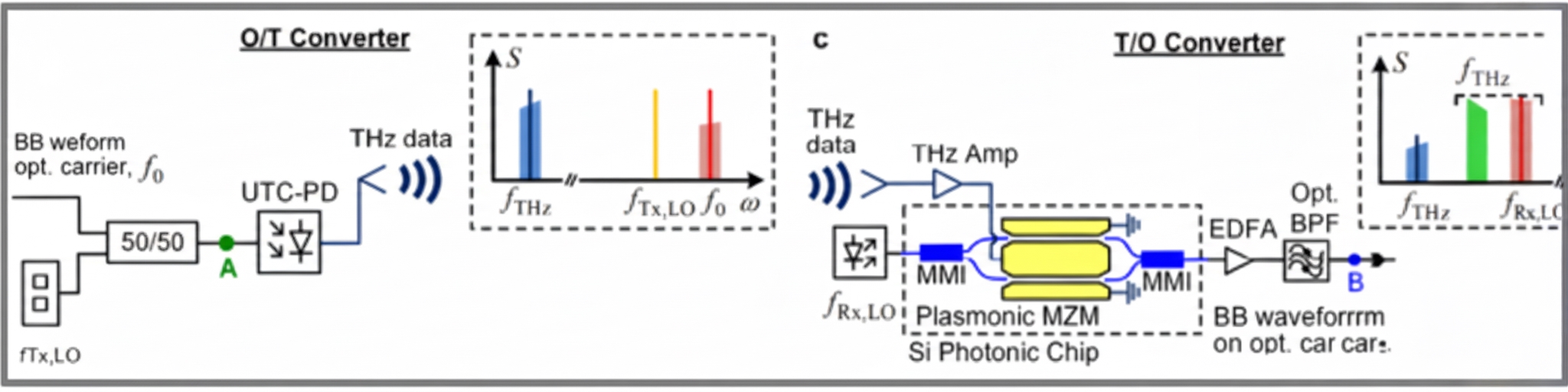

Basic interconnections are illustrated in Figures 1b and 1c. The scheme in Figure 1c mainly relies on an ultrawideband electro-optic modulator that provides modulation bandwidth extending into the THz spectrum. In Figure 1c, at the T/O converter the THz data signal is received by an antenna and fed to a THz amplifier. To convert it onto an optical carrier, the amplified signal is coupled into a POH Mach-Zehnder modulator (MZM), which is driven by an optical carrier at frequency fRx,LO. The MZM produces an upper and a lower modulation sideband; an optical bandpass filter (BPF) suppresses the carrier and selects one sideband, as shown in Figure 1c. That scheme allows operation across a wide range of THz frequencies and does not require downconversion to an intermediate frequency before encoding data onto the optical carrier, significantly reducing THz front-end complexity. After T/O conversion, the analog signal is sent back via fiber to an optical receiver (Opt. Rx) at the centralized DSP site.

Figure 1d shows a false-color scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the fabricated POH MZM. Light is coupled via on-chip grating couplers (not shown) into a silicon photonics (SiP) chip and propagates in the quasi-transverse electric (quasi-TE) mode through silicon strip waveguides (blue). A multimode interference (MMI) coupler splits the input light and sends it into the two arms of an unbalanced MZM. At the other end, an MMI coupler recombines the modulated signals into an output waveguide with a grating coupler. Each MZM arm contains a plasmonic-organic hybrid (POH) phase modulator section with a narrow metal slot (width w = 75 nm) between gold electrodes (yellow), as shown in Figure 1e. A pair of tapered silicon waveguides convert the silicon strip waveguide photon mode to the surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode in the metal-slot waveguide and back, see the inset in Figure 1e. The slot is filled with organic electro-optic material SEO100. A THz signal applied to the ground-signal-ground (GSG) contacts of the plasmonic MZM generates a THz electric field in the slots of both arms, producing optical phase shifts. As seen in Figures 1f and 1g, the quasi-TE optical field and the THz electric field are tightly confined in the plasmonic slot waveguide, yielding strong overlap and high modulation efficiency. The MZM is configured to operate in push-pull mode, with equal magnitude but opposite sign phase shifts in each arm. This is achieved by appropriately choosing the EO material polarization direction relative to the THz field modulation inside the two slot waveguides.